Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Chance Vought F7U Cutlass

Chance Vought F7U Cutlass

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

10 years agoSun Apr 28 2019, 03:50pm

Main AdminThe German aircraft industry had built up a remarkable technical background of extremely advanced aerodynamic concepts during World War II. Not only had they perfected the jet fighter to a degree of reasonable reliability, they were operating them in squadron strength. These planes were so advanced that the speeds at which they operated brought them onto the threshold of compressibility. This is a phenomenon which, expressed in its simplest terms, means that the aircraft moves so fast that the air molecules cannot move out of the way fast enough and become "compressed" around the airframe, often causing destructive results.

Main AdminThe German aircraft industry had built up a remarkable technical background of extremely advanced aerodynamic concepts during World War II. Not only had they perfected the jet fighter to a degree of reasonable reliability, they were operating them in squadron strength. These planes were so advanced that the speeds at which they operated brought them onto the threshold of compressibility. This is a phenomenon which, expressed in its simplest terms, means that the aircraft moves so fast that the air molecules cannot move out of the way fast enough and become "compressed" around the airframe, often causing destructive results.

The highly imaginative German engineers had already begun to attack the compressibility problems by designing aircraft with their flying surfaces angled sharply rearward. With the fall of Germany this research material became available to American designers toward the end of 1945. Among the material was found some data on tailless aircraft being studied by the German Arado Company. Guided by this data, Vought engineers devised an unorthodox twin jet carrier fighter which was proposed to the Navy during a design competition in 1946. Though radical in appearance, the tailless configuration promised a substantial performance advancement coupled with carrier compatibility. On June 25, 1946, three XFTU-1 prototypes were ordered, and the raked-wing shape inspired the name Cutlass.

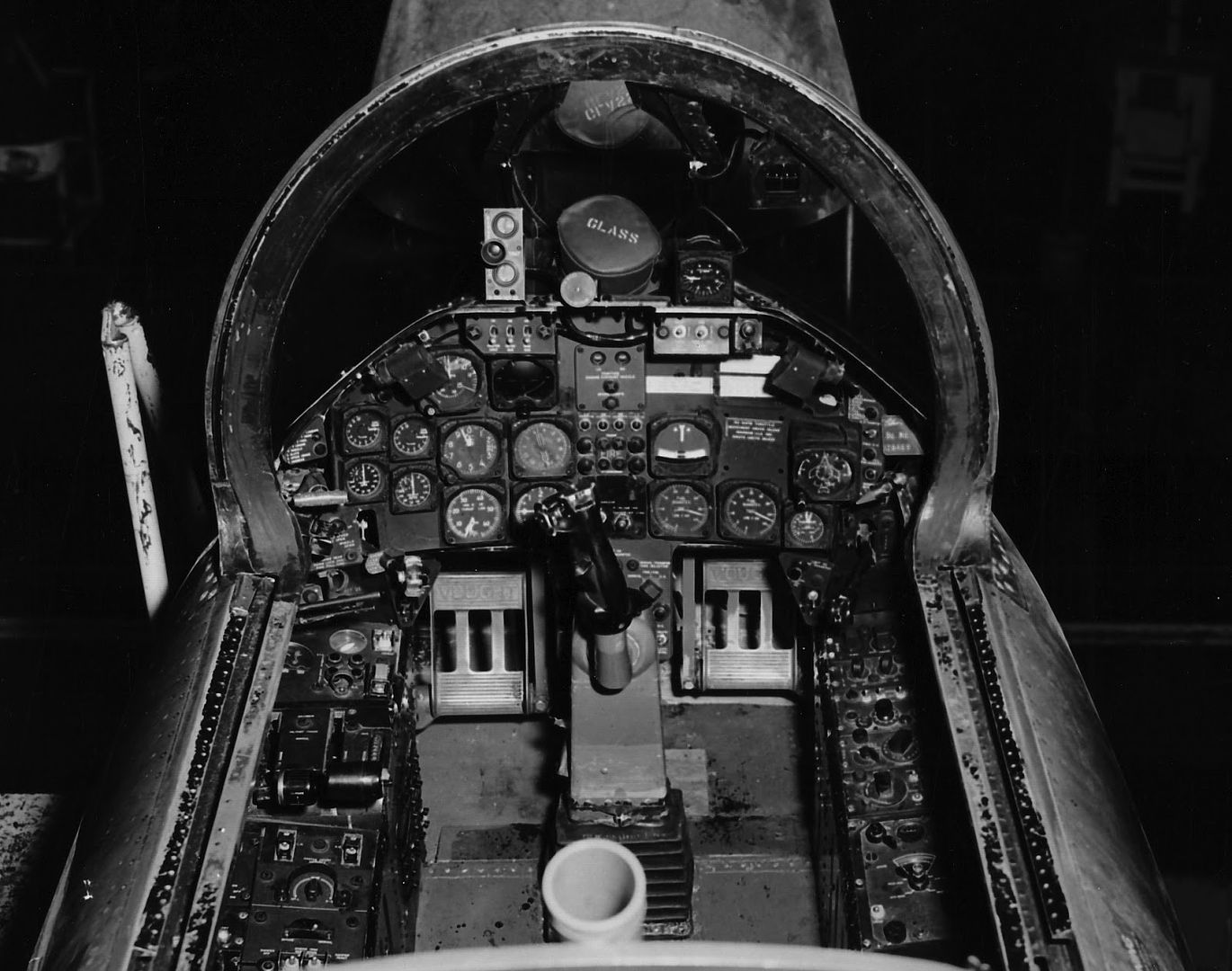

Such a bold departure from the conventional obviously had to produce some new devices for control, and the Cutlass displayed several of these. Since there was no horizontal stabilizing surface, the function of the elevators was taken over by large surfaces built into the wing trailing edges. Called "ailevators," they served the dual function of inducing roll as would conventional ailerons and pitch as elevators. The entire leading-edge of the wing was hinged to slide forward and down to alter the camber of the airfoil for slow speeds. Aerodynamic braking was achieved with a pair of split flaps between the vertical fins and the fuselage side. Operation of the controls from the cockpit was quite normal, however, and the pilot was provided with the conventional stick and rudder pedals for his part in the flight. The Cutlass was the first jet to be designed from the outset to incorporate afterburners. The first flight was made on September 29, 1948, from the Naval Air Test Center, now located at Patuxent River, Maryland. Although the second prototype Cutlass was lost on March 14, 1949, the plane had shown sufficient promise, and 14 F7U-1's had already been ordered for assembly at Vought's new Texas plant.

The teething problems that accompany a new prototype were found in abundance; and alterations were Vought F7U Cutlass In Flightrecommended for inclusion in 88 F7U-2's. But a vastly modified version was.now available, and the -2 stayed on paper while production turned instead to the F7U-3.

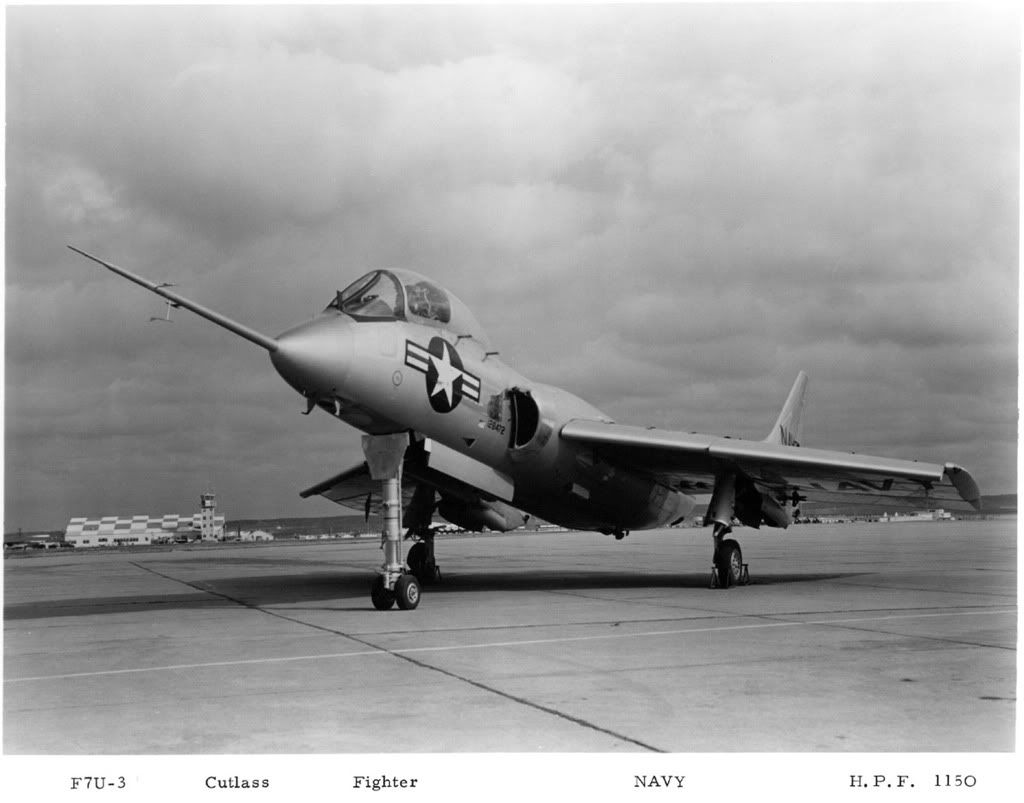

With the F7U-3, only the general arrangement of the original design remained. The XFTU-1 had an elongated nose strut to elevate the ground angle to increase the wing's angle of attack for catapult launching. On the prototypes, this angle was 9 degrees. To further improve the launch characteristics, this angle was increased to 20 degrees on the F7U-3. The four 20 mm cannons were moved from the nose on the F7U-1 to over the air inlets on Vought the later type. This led to some problems of smoke ingestion into the engines when the guns were fired, but this was solved by cut- ting vents into the skin behind the muzzles, Cockpit visibility was improved by enlarging the canopy and cutting the nose sharply down in front of the windshield.

In operations, the Cutlass proved to be structurally sound, and on occasion withstood up to 16 "G's" and -9 "G's" without damage. Its spinning characteristics were looked upon with considerable apprehension, however. Just before entering a stall, the Cutlass tended to flip end over. At that point, the pilot usually parted company with the ship. It was found, however, that by simply releasing the controls, the inherent stability of the design would assert itself and the Cutlass recovered by itself.

The first 16 F7U-3's were constructed with Allison J35-A-29's without after- burners when development problems slowed delivery of the power-booster. Sub- sequent F7U-3's were equipped with after- burning Westinghouse J46-WE-8 units of 4,000 lbs. of thrust normal, but boosted to 5,725 lbs. with afterburning.

Cutlasses were assigned to four Navy squadrons-VF-81, VF-83, VF-122 and VF- 124. Two of the tailless fighters were given to the Marines for high-speed mine-laying tests. In service, the Cutlass proved to be a problem child. Maintenance time was high and the fighter was subject to an excessive accident rate during carrier operations.

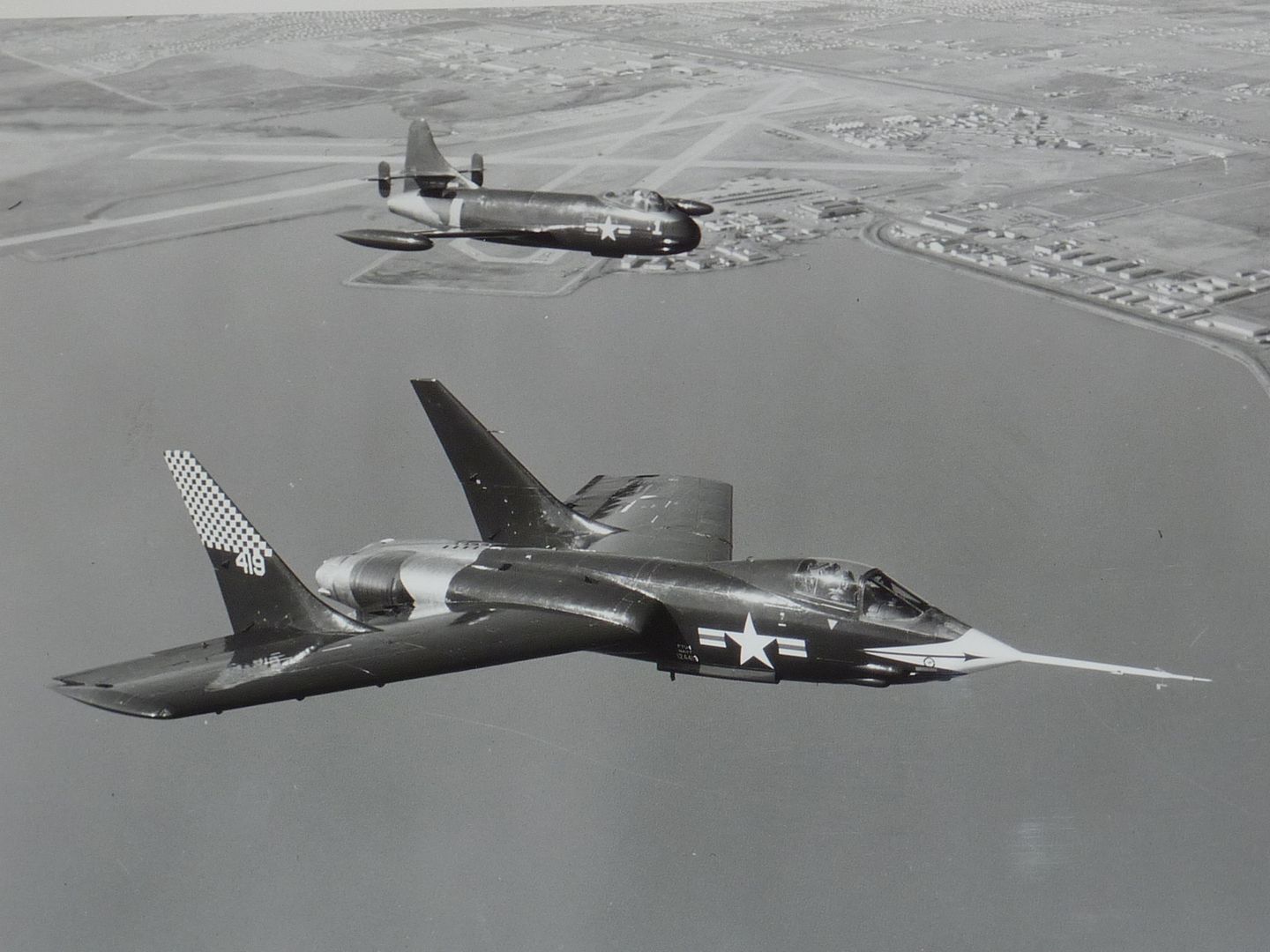

Two of the original F7U-1 Cutlasses were used by the Navy's Blue Angels demonstration team, their unique shape presenting a startling contrast to the rest of the team's F9F Panthers. The F7U-1 had two 3,000 lb. thrust Westinghouse J34-VE-32 engines and a wingspan of 38 feet 8 inches. Wing area was 4)6 square feet. Length was 39 feet 7 inches and height was 9 feet 10 inches. Empty and gross weights were 9,565 pounds and 14,505 pounds respectively. Maximum permissible weight was 16,840 pounds, which included 971 gallons of fuel. This provided a f.erry range of 1,170 miles. Maximum speed of the F7U-i with afterburning was 672 mph at 20,000 feet. Service ceiling was 41,400 feet.

The F7U-3 was somewhat larger than the -1 models. A total of 290 of this tyPe were built, including 98 F7U-3M's armed with four Sparrow missiles on underwing pylons to supplement the four cannons. Also included in the total are 12 F7U-3P reconnaissance machines. The F7U-3 used a pair of Westinghouse J46-VE-8A powerplants with 4,600 lbs. of thrust normally and 6,100 lbs. with afterburning. With this power, the maximum speed was 680 mph at 10,000 feet with a rate of climb of 13,000 fpm. Service ceiling was over 40,000 feet.

The F7U-3 wingspan was 39 feet 8 inches, length was 43 feet 1 inch, and height was 14 feet 7 inches. The Cutlass was not the Navy's first tailless aircraft. That distinction goes to the Burgess-Dunne AH-7 tailless biplane of 1916.

Design problems

In the spring of 1954, after six years of flight testing, three carrier suitability trials, and almost a decade of development, the first of 13 F7U-3 Cutlass fleet squadrons became operational. Early squadrons found out that the new! improved! Cutlass was also the most complicated to maintain. ?I flew around 380 hours in the jet and never once wrote Okay on the [maintenance] sheet,? Feightner says. ?There was never nothing wrong with it.?

All high-performance jets of the era?the North American FJ-1 Fury, the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, the McDonnell F2H-2 Banshee?had their share of unique incidents and accidents, but the sheer number of high-profile Cutlass misfortunes was tough to beat. Like the time Vought test pilot Paul Thayer ejected from a flaming prototype in front of an airshow crowd on July 7, 1950. Or when Lieutenant Floyd Nugent ejected on July 26, 1954, only to watch the Cutlass, loaded with 2.75-inch rockets, fly serenely on, orbiting San Diego?s North Island and the Hotel Del Coronado for almost 30 minutes before ditching near the shore. When the left engine on Lieutenant Commander Paul Harwell?s Cutlass caught fire moments after takeoff on May 30, 1955, Harwell ejected and never set foot in the F7U again?giving him more time in a Cutlass parachute than in the actual aircraft. An electrical failure forced Tom Quillin to abort a training mission and declare an emergency. Quillin returned to base only to learn he was number three in the emergency landing pattern, behind two of the three other Cutlasses he took off with.

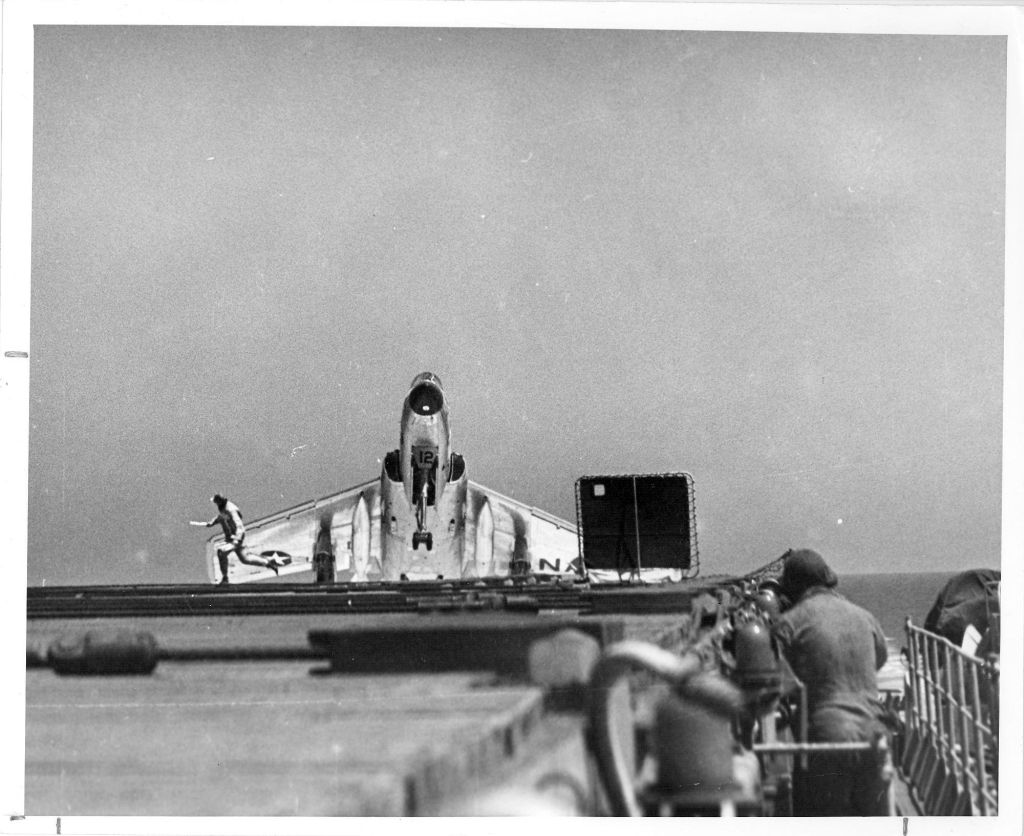

On December 11, 1954, during a low-altitude, high-speed pass before thousands of onlookers at the christening of the USS Forrestal at Newport News, Virginia, Lieutenant J.W. Hood?s F7U-3 suffered a wing-locking mechanism malfunction. The airframe came apart, an engine blew up, and Hood was killed when he was catapulted into the water. On July 14, 1955, before the first deployment of a Cutlass squadron at sea, an F7U-3M Cutlass pilot flying carrier qualifications off the coast of San Diego was waved off as too low on approach to the USS Hancock. In a sequence shot by Navy camera crews, the Cutlass, flown by Lieutenant Commander Jay Alkire, is descending, though its nose is pointing skyward. The landing signal officer sprints across the flight deck only moments before the Cutlass hits the carrier, breaks apart, and falls over the side as a fireball consumes the tail end of the ship. Alkire was killed.

The F7U-3 shared a design flaw with the F7U-1: two anemic Westinghouse jet engines. The company promised Vought and the Navy it could build an engine for the -3 that would generate 10,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner. By the time the J-46-WE-8A was delivered, Westinghouse had dropped the estimate by 10 percent. Later evaluations indicated it could put out no more than 6,100 pounds. And no existing engine would fit the Cutlass? airframe.

Vought engineers, concerned about the kickback load on the nose landing gear actuator and mounting structure, added small turbines, powered by engine bleed air, to pre-spin tire on the nosegear tires to 90 mph. But the nosegear strut continued to fail, despite efforts to reinforce the structure by 30 percent. A weak drag link brace tended to give out during landing.

The USS Hancock, like most aircraft carriers of the day, had a straight deck (the switch to angled decks began in the mid-1950s). To come to a stop before running out of deck or into the aircraft parked at its far end, pilots were required to grab an arresting wire with the aircraft?s tailhook or rely on a series of canvas safety nets and metal cables. On November 4, 1955, when Lieutenant George Milliard tried to land, the tailhook on his Cutlass floated over all 12 arresting wires. Too low and slow to go around, Milliard went into the barrier, where the nosegear failed. The strut drove up into the cockpit and into the base of the ejection seat, triggering the ejection seat firing mechanism and knocking off the canopy. Milliard was launched 200 feet forward. He hit the tail of a Douglas A-1 Skyraider and later died of his injuries.

The Hancock?s skipper ordered every Cutlass off the ship. VF-124 spent the majority of its western Pacific cruise at the naval airfield in Atsugi, Japan. Two months later, after a Cutlass nosegear collapse on the Ticonderoga left its pilot with severe back injuries, the carrier?s skipper ordered the Cutlasses of VF-81 ashore at Port Lyautey, Morocco. ?You got to understand, the commanding officer of a carrier is the lord, God, and everything else of that carrier,? says Don Shelton, who in the early 1950s was a Navy test pilot on the Cutlass program. ?Most of them didn?t appreciate having the F7U aboard.?

?The skippers never really liked it because it took up a lot of space and they never could really do anything with the airplane,? says Feightner. ?The Cutlass was pretty short-legged.? Soon after launching from a carrier, the pilots had to begin thinking about where to put the thing down. ?They used to say if you put a 3,000-pound bomb on it, you couldn?t go far enough to keep from blowing up both you and the ship,? Feightner says.

Then there was the post-stall gyration.

On January 11, 1955, Lieutenant J.D. Lindsay was at 28,000 feet when his maneuvering brought him close to a stall. Suddenly the F7U-3 went head over heels. Violently thrown about the cabin, Lindsay ejected and survived. Nine days later, Lieutenant Commander Bud Sickel investigated the flight regime that had caused the loss of Lindsey?s Cutlass. After tumbling 18,000 feet and trying every recovery technique he could think of, Sickel ejected.

?It was a pretty wild ride,? says Shelton. ?He got out just in time for the parachute to open and landed in a plowed field and went in all the way up to his hips, which was the only thing that saved his ass.?

When Lieutenant Morrey Loso found himself in a similar situation, he let go of the stick and fumbled for the overhead ejection handles. To his astonishment, the Cutlass leveled off. Subsequent wind tunnel testing confirmed that the usual rules for exiting uncontrolled flight didn?t apply to the Cutlass. Just a little aft pressure on the stick, or let it go entirely: With enough altitude, the airplane would likely recover on its own. But by then, the Cutlass? reputation was such that Vice Admiral Harold M. ?Beauty? Martin, commander, air force of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, began replacing his squadrons? Cutlasses with Grumman F9F-8 Cougars.

Even those who liked the airplane admit it had its shortcomings, but maintain that if the Navy had spent the time and money to adequately address them as it had for airplanes like the Vought F-8 Crusader or the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, the F7U could have been a sweeter ride. Supporters say it was a necessary step in the advancement of naval aviation, and that while the numbers were bad, so were the numbers of just about everything involving jet fighters and aircraft carriers in the early to mid-1950s.

Ultimately, between June 1954 and December 1956, 13 fleet squadrons received Cutlasses. In 1957, Chance Vought analyzed major F7U-3 accidents. At 55,000 hours cumulative flight time, 78 accidents, and one-quarter of airframes lost, the Cutlass had the highest accident rate of all Navy swept-wing fighters.

General characteristics

Crew: 1

Length: 41 ft 3.5 in (12.586 m)

Wingspan: 39 ft 8 in (12.1 m)

Span wings folded: 22.3 ft (6.80 m)

Height: 14 ft 0 in (4.27 m)

Wing area: 496 sq ft (46.1 m2)

Empty weight: 18,210 lb (8,260 kg)

Gross weight: 26,840 lb (12,174 kg)

Max takeoff weight: 31,643 lb (14,353 kg)

Powerplant: 2 ? Westinghouse J46-WE-8B after-burning turbojet engines, 4,600 lbf (20 kN) thrust each dry, 6,000 lbf (27 kN) with afterburner

Performance

Maximum speed: 606 kn (697 mph; 1,122 km/h) at sea level with Military power + afterburner

Cruise speed: 490 kn (564 mph; 907 km/h) at 38,700 ft (11,796 m) to 42,700 ft (13,015 m)

Stall speed: 112 kn (129 mph; 207 km/h) power off at take-off

93.2 kn (173 km/h) with approach power for landing

Combat range: 800 nmi (921 mi; 1,482 km)

Service ceiling: 40,600 ft (12,375 m)

Rate of climb: 14,420 ft/min (73.3 m/s) with Military power + afterburner

Time to altitude: 20,000 ft (6,096 m) in 5.6 minutes

30,000 ft (9,144 m) in 10.2 minutes

Wing loading: 50.2 lb/sq ft (245 kg/m2)

Thrust/weight: 0.29

Take-off run: in calm conditions 1,595 ft (486 m) with Military power + afterburner

Armament

Guns: 4 20mm M3 cannon above inlet ducts, 180 rpg

Hardpoints: 4 with a capacity of 5,500 lb (2,500 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

Missiles: 4 AAM-N-2 Sparrow I air-to-air missiles

XF7U-1

Three prototypes ordered on 25 June 1946 (BuNos 122472, 122473 & 122474). First flight, 29 September 1948, all three aircraft were destroyed in crashes.

F7U-1

The initial production version, 14 built. Powered by two J34-WE-32 engines.

F7U-2

Proposed version, planned to be powered by two Westinghouse J34-WE-42 engines with afterburner, but the order for 88 aircraft was cancelled.

XF7U-3

Designation given to one aircraft built as the prototype for the F7U-3, BuNo 128451. First flight: 20 December 1951.

F7U-3

The definitive production version, 192 built. Powered by two Westinghouse J46-WE-8B turbojets.

F7U-3P

Photo-reconnaissance version, 12 built. With a 25 in longer nose and equipped with photo flash cartridges none of these aircraft saw operational service, being used only for research and evaluation purposes.

F7U-3M

This missile capable version was armed with four AAM-N-2 Sparrow I air-to-air beam-riding missiles, 98 built. A total of 48 F7U-3 existing airframes were upgraded to F7U-3M standard. An order for 202 aircraft was cancelled.

A2U-1

Designation given to a cancelled order of 250 aircraft to be used in the ground attack role.

Regards Duggy

LINK to a Video -- showing landings (viewer discretion advised)-- http://www.texasarchive.org/library/index.php?title=Vought_F7U-3_Aircraft_Carrier_Crash_Landings

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources