Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Lockheed Starfighter

Lockheed Starfighter

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

Main AdminSTARFIGHTER ORIGINS / XF-104

Main AdminSTARFIGHTER ORIGINS / XF-104

In late 1951, the Lockheed company's chief aircraft designer, Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson, went to South Korea to talk with US fighter pilots engaged in the air war there to ask them what they were looking for in a next-generation fighter. The answer was that they wanted a simple, lightweight fighter that provided high speed, altitude, and maneuverability. In December 1951, Johnson proposed that he begin development of such a machine, even though the USAF had no outstanding requirement for it at the time.

By the end of October 1952, a range of different designs had been considered and screened down to a concept designated the "Model L-246", envisioning an aircraft with a dartlike fuselage, short trapezoidal wings, a tee tail, and a new-generation, powerful turbojet engine, the General Electric (GE) J79. Lockheed management liked the concept, and that November Johnson went to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio to pitch the L-246 to the Air Force.

At the time, the USAF was engaged in wide range of advanced aircraft development programs, and the idea that the service might have wanted to take on another seems a bit implausible in hindsight -- but the Cold War was on in earnest, and in fact the hot war in Korea was still in progress as well. There was much less bureaucracy involved in developing combat aircraft in those days, partly because they were much simpler and less expensive to design and build than they are now.

In any case, the Model L-246 was so attractive that the USAF got on board quickly, though the service still had to issue a request for proposals to industry and conduct a competition. Northrop, North American, and Republic submitted designs that made it into the final round of the competition, but Lockheed had the head start and won the award in January 1953. The contract that followed specified construction of a mockup, already being put together at Lockheed, plus a static test aircraft and two flight prototypes. Lockheed designated the aircraft the "Model 83"; the Air Force designated the program "Weapon System (WS) 303A", and gave the prototypes the designation of "XF-104".

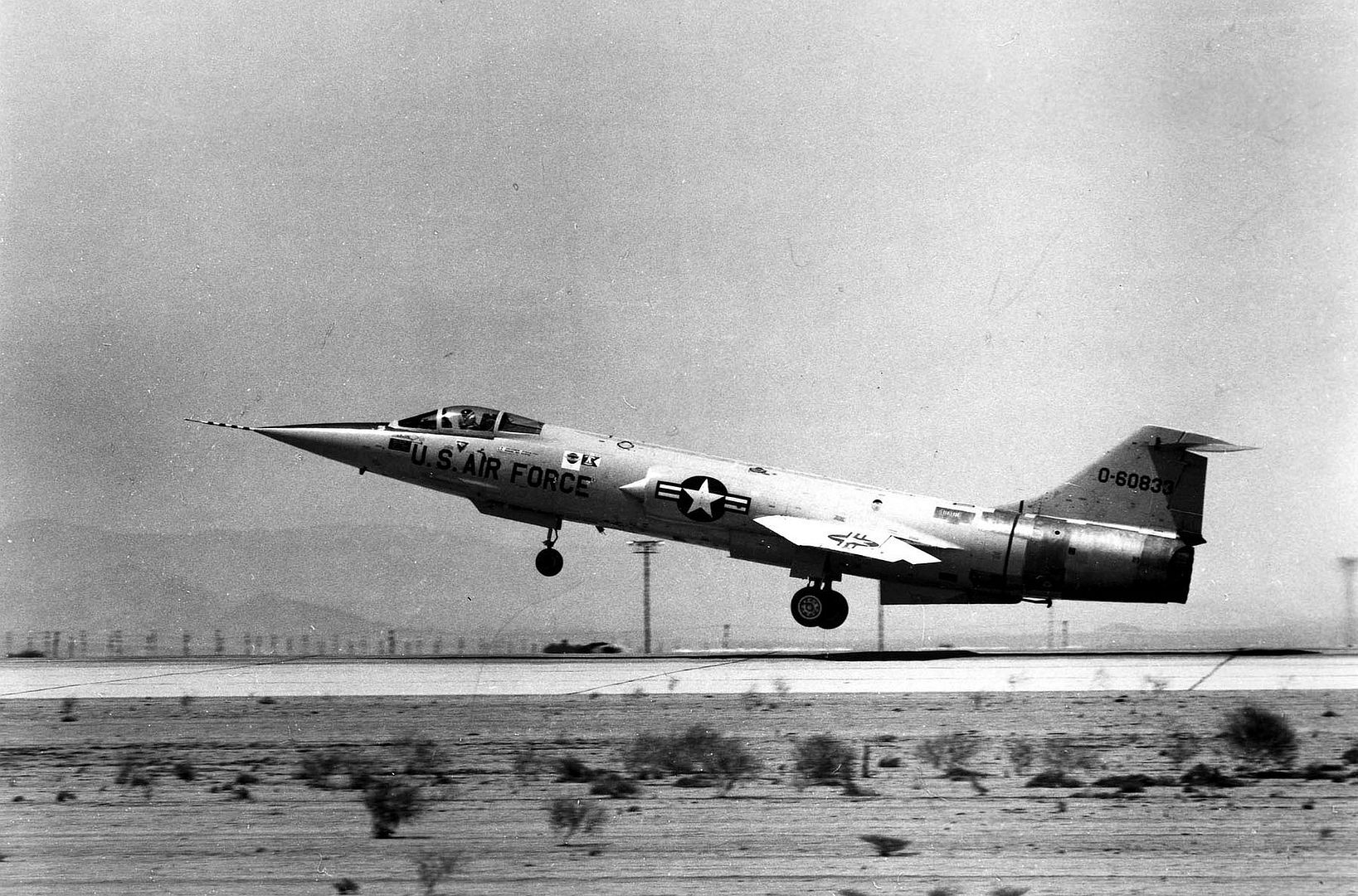

Tony Levier was assigned to fly the aircraft. He found the design exotic and impressive, but it was so new in concept that he had concerns about how well it might fly. The first XF-104 was rolled out from the Lockheed plant in Burbank, California, on 23 February 1954, and was quietly trucked to Edwards AFB the next evening.

The XF-104 was a sleek dart of an aircraft, no doubt breathtakingly advanced in appearance compared to contemporary jet fighters in service. It was made mostly of aviation aluminum alloys, with titanium near the engine exhaust. It had a needle nose, a bubble-style canopy that hinged open to the left, trapezoidal thin sharp-edged wings with a noticeable anhedral droop, a tee tail, and tricycle landing gear. All three gear assemblies had single wheels, with the steerable nose wheel retracting backward and the main gear rotating and tucking forward into the fuselage. The XF-104 featured a downward-firing ejection seat, chosen because an upward-firing ejection seat stood a chance of tossing the pilot into the tail assembly. Minimum ejection altitude was given as 152 meters (500 feet). To no surprise in hindsight, the downward-firing ejection seat would not turn out to be a good idea.

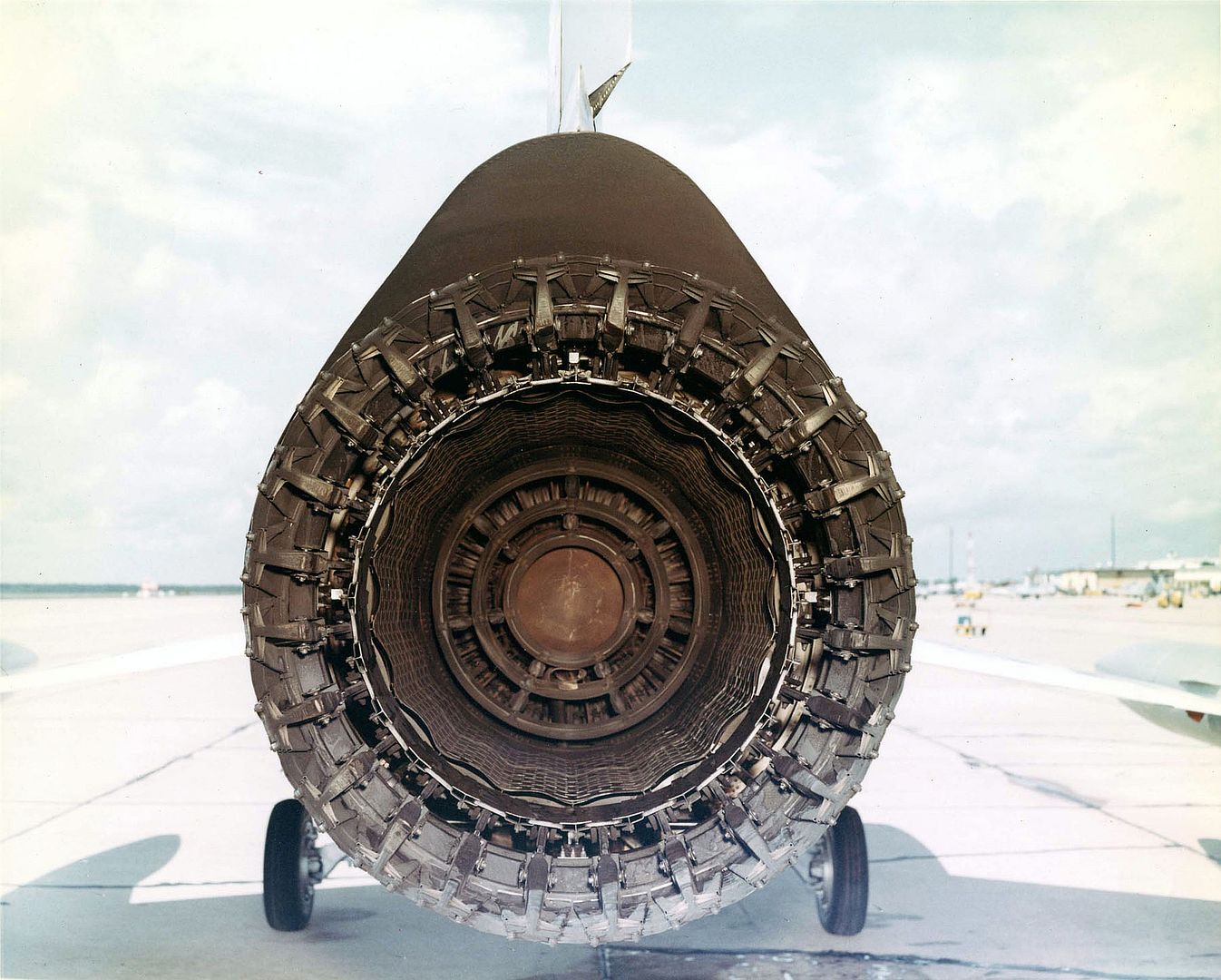

Since the GE J79 wasn't available at the time, the first XF-104 was temporarily fitted with a Buick-built Wright J65-B-3 non-afterburning turbojet, which would be upgraded to an afterburning J65-W-7 version in July 1954. The J65 was an "Americanized" version of the British Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire axial-flow turbojet. The J65-W-7 provided 34.7 kN (3,540 kgp / 7,800 lbf) dry thrust and 45.8 kN (4,670 kgp / 10,300 lbf) afterburning thrust -- only about 70% of the power expected from the GE J79. The J65 was fed through half-circle fixed intakes on either side of the fuselage forward of the wing roots. The intakes were set off from the fuselage slightly to ensure that they didn't ingest turbulent and stagnant "boundary layer" air that hugged the fuselage.

Levier began taxi tests on 27 February and took the machine on a short hop up from the runway and down again on 28 February. The first full flight was on 5 March, but it was short-lived, since the landing gear wouldn't retract -- that was certainly much better than retracting and then refusing to go back down, but it still indicated a problem. Lockheed technicians made fixes on the spot, but the second flight went no better: the landing gear still wouldn't retract. Between engineering work and bad weather, the next flights didn't take place until near the end of March. However, by that time the XF-104 was flying right, though test flights through the spring and into the summer of 1954 continued to turn up the more or less expected bugs and glitches.

Even with the non-afterburning J65-B-3 engine, the XF-104A could break Mach 1 in level flight, with the transition so smooth that the pilot hardly knew it had happened; Mach 1 was no longer the obstacle that it had been thought to be in the previous decade. Once the afterburning J65-W-7 was installed, the XF-104 could do Mach 1.5 with no particular difficulty, and on 15 March 1955 it broke Mach 1.79. Everyone involved with the project must have reflected on the enormous jump in aircraft performance over the space of a mere decade.

The second XF-104 was already in the air by this time, having performed its first flight on 6 October 1954. It was fitted from the outset with the afterburning J65-W-7. This aircraft was primarily intended for armament tests. Although the original idea was that the machine would be fitted with twin 30-millimeter cannon, a decision was made to go with the new high-speed GE TE-171-E3 (later M61) "Vulcan" six-barreled Gatling 20-millimeter cannon. The aircraft was also fitted with the AN/ASG-14T-1 fire control system (FCS).

The cannon tests ran into snags: on 17 December 1954, Levier tried to fire a burst at high altitude and was rewarded with an explosion. The engine began running rough and Levier shut it down, gliding 80 kilometers (50 miles) to put the machine down safely. As it turned out, a 20-millimeter cartridge had exploded while being fired, blowing off the back of the cannon and sending it through the section of the aircraft behind it. In a sense, the XF-104 had shot itself down.

The aircraft was repaired and returned to flight test. However, on 14 April 1955 Lockheed test pilot Herman R. "Fish" Salmon was performing cannon tests, setting up vibrations so severe that they blew off the ejection seat door in the bottom of the cockpit. The cockpit depressurized and Salmon's pressure suit puffed up so much that he couldn't see what was going on. Had he understood the problem he could have gone to low altitude, equalizing the pressure and allowing him to get things under control, but he had no real idea of what had gone wrong and decided to eject, coming to earth safely. Of course, the second prototype cratered into the ground and was destroyed. An F-94C Starfire interceptor was modified to complete the armament tests.

The first XF-104 would also be lost in a crash later. On 11 July 1957, Lockheed test pilot William M. "Bill" Park -- who would later fly the HAVE BLUE demonstrator that led to the F-117 Stealth Fighter -- was flying the XF-104 as a chase plane when flutter tore the tail off. Park ejected safely and the aircraft fell to earth.

-

6 years agoSat Jul 20 2019, 10:58am

Main AdminYF-104A / F-104A

Main AdminYF-104A / F-104A

The loss of the prototypes didn't slow the program down. The USAF had awarded Lockheed a contract for 17 "YF-104" pre-production evaluation machines on 30 March 1955. By the end of the year, GE was shipping YJ79-GE-3 evaluation engines to Lockheed, and the first YF-104A performed its initial flight on 17 February 1956. Herman Salmon was at the controls, obviously not overly fazed by his ejection from the number-two XF-104 just two days earlier. The YF-104 broke Mach 2 on 28 February.

The YF-104A was 1.68 meters (5 feet 6 inches) longer than the XF-104 to allow it to accommodate the J79 engine, with the stretch allowing it to carry more fuel as well. It also introduced a new inlet scheme, featuring a fixed half-cone in each inlet. The half-cones were called "shock cones" or more informally "flight falsies" -- a "falsie" being Yank slang for a padded brassiere -- and the scheme was a big secret at the outset. The nosewheel assembly was also changed to retract forward, to provide better clearance for the downward-firing ejection seat. Other minor changes involved a taller tailfin and a dorsal spine.

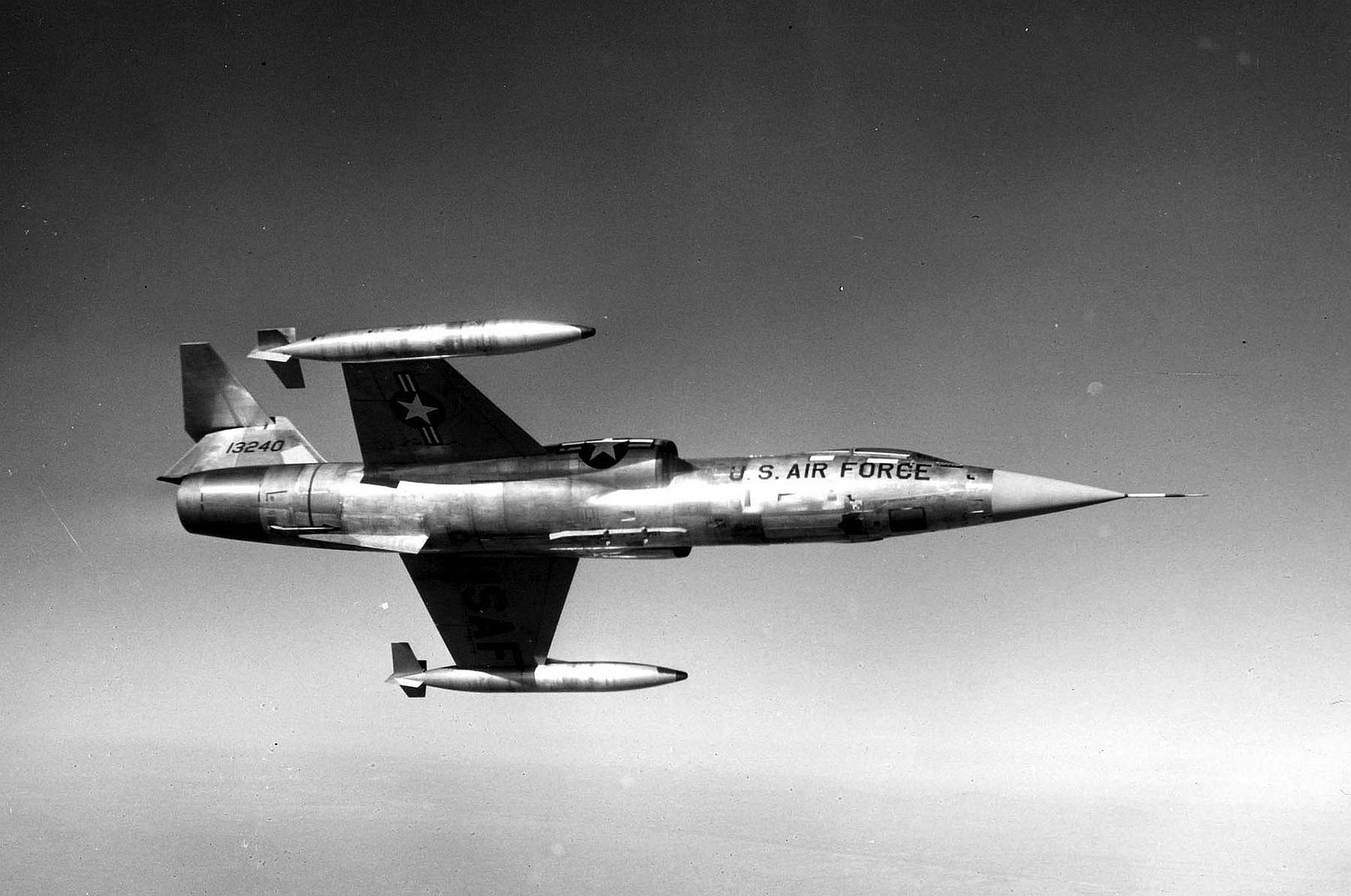

The YF-104s were intended to evaluate the J79 engine, the GE M61 Vulcan cannon, the AIM-9 (originally GAR-8) Sidewinder air-to-air missile (AAM), and wingtip fuel tanks with a capacity of 644 liters (170 US gallons) each, as well determine the Starfighter's flight envelope. The YJ79-GE-3 evaluation engines provided 65.9 kN (6,715 kgp / 14,800 lbf) afterburning thrust.

The USAF seemed more or less sold on the F-104, awarding Lockheed a contract on 2 March 1956 for an initial batch of production aircraft. The contract actually specified four different Starfighter variants:

The "F-104A" single-seat daylight interceptor for the USAF Air Defense Command (ADC).

The "F-104B" two-seat trainer derivative of the F-104A.

The "F-104C" single-seat fighter-bomber for the USAF Tactical Air Command (TAC).

The "F-104D" two-seat trainer variant of the F-104C.

The next month, the Starfighter was finally unveiled to the public, the program having been kept as secret as possible to that time. Initial photographs featured a YF-104 with the intakes covered by neat fairings to conceal the intake cones.

Late in 1956, Lockheed got a contract for a dedicated reconnaissance version of the Starfighter, designated the "RF-104A" and at least informally known as the "Stargazer". However, this contract was canceled within a few months, the Air Force deciding to focus on the McDonnell RF-101 Voodoo for the tactical reconnaissance mission. Reconnaissance Starfighters would fly, but not with the USAF.

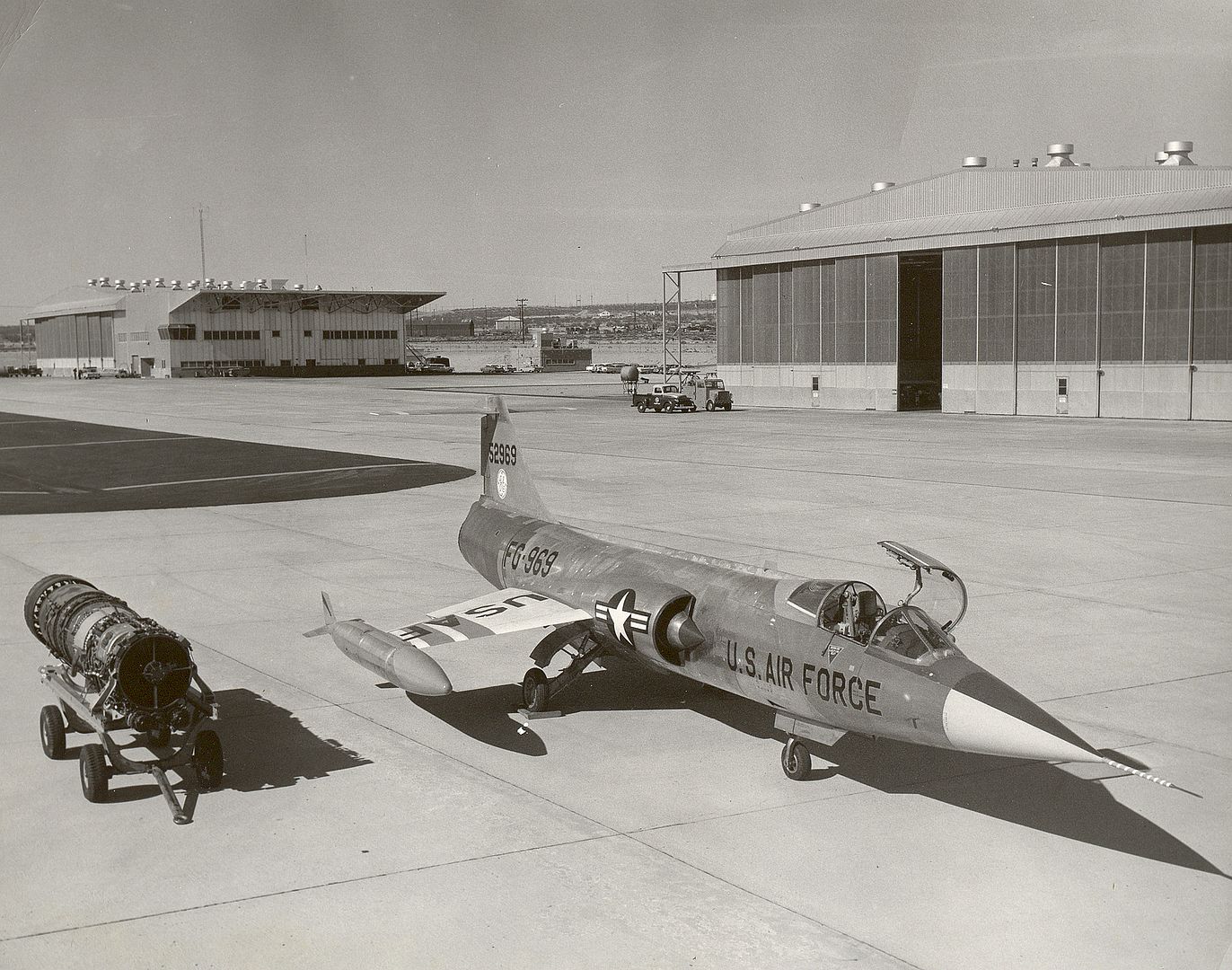

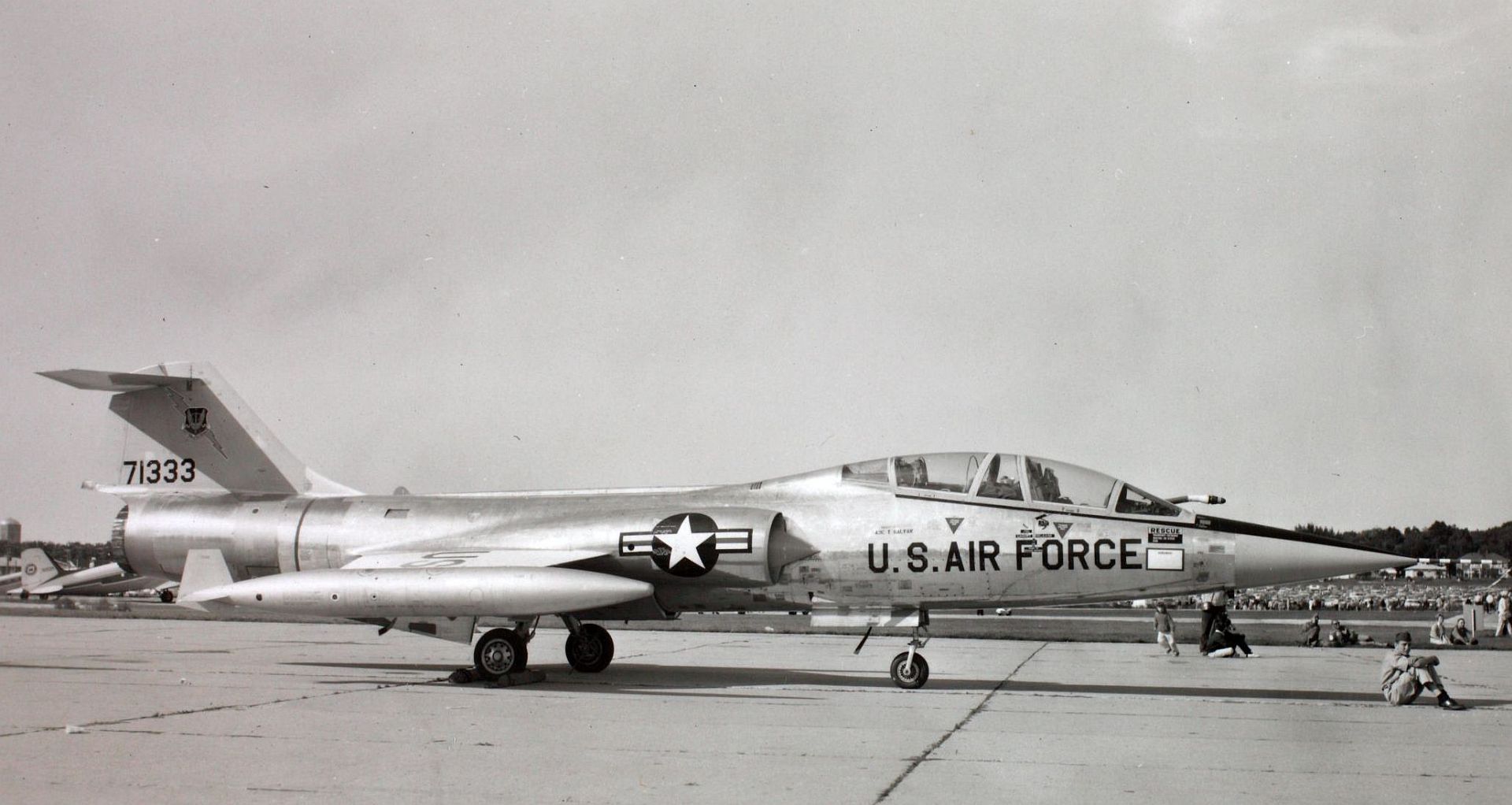

* The F-104A entered formal USAF service in late February 1958. Its form followed that of the YF-104A, being a dartlike machine with trapezoidal wings, a high tee tail, and tricycle landing gear, though the airframe had been reinforced to handle higher gee stresses. It was powered by a J79-GE-3B turbojet engine, which had similar performance to the earlier -3 and -3A engines used on the YF-104As, but was more reliable. The early J79 variants were badly prone to engine failures; it appears that early F-104A production used the -3A variant, but it was quickly replaced when the -3B became available. The engine could be accessed by pulling off the rear fuselage after undoing four bolts. The Starfighter had been designed to be easy to maintain, and it was regarded as very maintainable by the standards of the time. There was a ram-air turbine (RAT) in a pop-out door on the lower right side of the fuselage, just behind the nose gear, to provide electrical and hydraulic power in case of systems failure.

The wing had twin spars, a leading-edge sweep of 26 degrees, a trailing-edge sweep of 18.1 degrees, a ratio of wingroot length to thickness of 3.36%, and an anhedral droop of ten degrees. The edges were sharp enough to require that they be covered with felt strips during maintenance to keep from gashing the ground crews. Each wing had a full-span leading-edge flap, and a large trailing-edge flap inboard of the aileron. Engine bleed air was fed through a slot on the top of the wing just forward of each trailing-edge flap, with this "blown flaps" or "boundary layer control (BLC)" scheme further improving low-speed handling. The Starfighter is said to have been the first production aircraft to feature BLC. Despite the small wings and the sleek fuselage, the landing speed was comparable to that of existing fighters, though still on the "hot" side, and so a ribbon-style brake parachute was fitted, popping out from under the tail of the aircraft.

The high tee tail had a conventional rudder with hydraulic power boost, but an all-moving tailplane. The tee configuration was selected to provide a longer "lever arm", improving the effect of the elevators. It did tend to undermine roll stability, and so the last YF-104A evaluated a ventral fin that was then flowed into production. Some sources claim early production F-104As did not have the ventral fin, but these machines appear to be YF-104As that were brought up to operational spec.

A runway arresting hook was fitted offset to the right and behind the ventral fin, but many pictures of F-104As do not show the arresting hook, and it appears to have been a late addition in production. The introduction and retrofit of features implies that the configuration of the F-104A was something of a moving target; in fact, the precise configuration of early Starfighter variants is a confusing subject in general, with many small contradictions between sources.

The sole armament of the F-104A was the heat-seeking AIM-9B Sidewinder, with one carried on each wingtip. Wingtip tanks could be carried as well, but of course missile armament could not be carried if the wingtip tanks were fitted. Sources indicate that it could also carry the MB-1 Genie AAM, an unguided weapon with a small nuclear warhead, launched from a trapeze under the fuselage. Apparently this was never more than a trial fit, and if there are any images of a Starfighter with a Genie, they're hard to find.

Although the F-104A was to carry the GE Vulcan cannon -- firing out a blister on the left side of the fuselage below the cockpit and belt-fed from an ammunition drum with a capacity of 725 rounds -- GE was having big problems getting the Vulcan to work. As a result, it was dropped from the F-104A. GE would finally introduce the serviceable M61A1 Vulcan variant in 1959, and F-104As would be gradually refitted with the cannon.

The F-104A could be fitted with a single stores pylon under each wing for use with external tanks, with each underwing tank having a capacity of 739 liters (195 US gallons). These underwing pylons were not fitted for carriage of Sidewinder AAMs, and were apparently never used for carrying anything but external tanks. Some sources insist that the F-104A didn't have the underwing pylons, but this is contradicted by manufacturer's drawings.

Avionics included the AN/ASG-14T-1 FCS, a TACAN beacon-navigation system, and radio. There was also an infrared sight, manifested by a little window at the bottom of the windscreen, but sources are very vague about its details. It is an indication of how much more complicated aircraft are today when statistics for an F-104A in contemporary dollars give the price of the entire aircraft as a little over $1.7 million USD, with avionics amounting to only a bit over $3,400 USD of that. These days, that would hardly buy a high-end home high-definition TV system -- much less a state-of-the art fighter radar, navigation / communications system, and countermeasures suite.

153 F-104As were built, not counting the 17 YF-104As, with the last batch accepted by the USAF in December 1958. As mentioned, some of the YF-104As were brought up to production spec and put into service.

While the Starfighter was being brought into operational service, it was also breaking performance records. On 7 May 1958, USAF Major Howard C. "Scrappy" Johnson took the world altitude record, flying a YF-104A to meters (91,249 feet) over Edwards AFB. On 16 May, a YF-104A flown by USAF Captain Walter Irwin set a world speed record, traversing a 15 x 25 kilometer (9.3 x 15.5) mile circuit at Edwards at an average speed of 2,260.75 KPH (1,404.19 MPH). In December 1958, an F-104A flying out of the naval air station at Point Mugu, California, set a series of climb rate records.

-

Main AdminF-104B

Main AdminF-104B

The initial flight of a two-seat F-104B was on 16 January 1957. The first aircraft was called the "YF-104B", but it was on the books simply as an F-104B. The F-104B was a fairly minimal change from the F-104A, with both variants having the same length. Fitting the twin cockpit required removing the Vulcan cannon; some sources claim the cannon could be refitted, but this seems to be an error. External stores capability and avionics were exactly the same as for the F-104A. Lockheed had offered the USAF a two-seater without combat capability, designated the "TF-104A", but the Air Force turned it down.

The nosewheel reverted to the backward-retracting configuration used on the YF-104A to deal with the modified crew arrangement, and the tailfin was extended back over the exhaust to increase its area by 25% to provide better yaw control, compensating for the aerodynamic interference of long tandem canopy. The rudder was larger, and so power actuation was added. The back seat was raised to give the instructor a good forward view. Each cockpit had its own canopy, hinging open to the right.

The F-104B went into formal USAF service in early 1958, in parallel with the F-104A. A total of 26 F-104Bs was built. Although apparently some consideration was given to using the F-104B as an advanced trainer for cadet pilots, in practice the type was used as a conversion trainer, with a few two-seaters supplied to F-104A squadrons to get fresh pilots up to speed on the idiosyncrasies of flying the Starfighter.

-

Main AdminF-104C

Main AdminF-104C

The first single-seat F-104C fighter-bomber variant made its initial flight on 24 July 1958 and began to go into service late in that year, essentially taking up the slack as F-104A production tapered off. The F-104C was hard to tell from the F-104A, the most distinctive difference being that the F-104C could be fitted with a fixed inflight refueling probe to the right of the cockpit for probe-&-drogue refueling.

The F-104C also added a centerline pylon, essentially to carry a parachute-retarded nuclear store. Some sources claim the centerline pylon was "wet", capable of carrying an external fuel tank; that F-104As could be fitted with the centerline pylon; and the F-104C's underwing pylons were wired for Sidewinder carriage; but all these assertions seem to be incorrect. The F-104C's centerline pylon could be fitted with a "catamaran" double stores rack for two Sidewinders, but the rack caused too much drag and was rarely carried. The F-104C's primary weapon for the strike role was the B28 nuclear store. Depending on variant, the B28 could have yields of from 70 kilotons to 1.45 megatons.

Internally, the F-104C featured the full-specification AN/ASG-14T-2 FCS and an improved J79-GE-7A engine, with 44.5 kN (4,535 kgp / 10,000 lbf) dry thrust and 70.3 kN (7,170 kgp / 15,800 lbf) afterburning thrust. The despised downward-firing ejection seat was replaced by a much more satisfactory Lockheed C-2 rocket-boosted upward-firing ejection seat.

A total of 77 F-104Cs was built, all delivered from late 1958 into late 1959. An F-104C set a new world altitude record on 14 December 1959, reaching 31,513 meters (103,389 feet) in 15 minutes 4.92 seconds. It was the first time an aircraft that took off under its own power had exceeded the 100,000 foot mark.

-

6 years agoMon Jul 22 2019, 08:51pm

Main AdminF-104D

Main AdminF-104D

The two-seat F-104D could be seen as an F-104B with much the same enhancements as the F-104C had over the F-104A, including the refueling probe, centerline pylon, J79-GE-7A engine, C-2 ejection seats, and enhanced avionics. The canopy was distinctively modified, however, by adding a fixed center section between the front and back seat cockpits, a feature associated with fit of the upward-firing ejection seats, possibly to provide a blast screen. Initial flight was on 31 October 1958, and 21 were built, in parallel with the F-104Cs.

[url] [/UR]

[/UR]

STARFIGHTER IN US SERVICE

The Starfighter had a generally short-lived and undistinguished career in USAF service, with the Air Force buying less than half the total number of machines initially planned. In fact, at the outset the Starfighter's most noticeable characteristic was its high accident rate, with 49 lost up to 1961. Partly the problem was the type's unprecedented high performance; partly the problem was its immaturity, J79 engine failures being a particular trouble; and partly the problem was that even when everything was working right, it was a demanding aircraft and not friendly to inexperienced pilots.

The downward-firing ejection seat was a very unpopular feature, since it meant that surviving a failure at low altitude was very unlikely. Pilots were supposed to try to roll the aircraft over for a low-altitude escape, but that was not necessarily easy to do. Well-known test pilot and ace Iven C. Kincheloe was killed in an F-104A at Edwards AFB on 26 July 1958; he tried to roll over, but ended up punching out sideways.

The F-104A's combat utility was marginal at best. It lacked the combat avionics of a proper interceptor and in hindsight its armament was inadequate. Many sources complain about its limited range, but the type's defenders insist that it was comparable to other fast combat jets of the time, none of which had very good range if afterburner were engaged for long periods. The F-104C was more satisfactory, basically the machine that Kelly Johnson had been hoping to build.

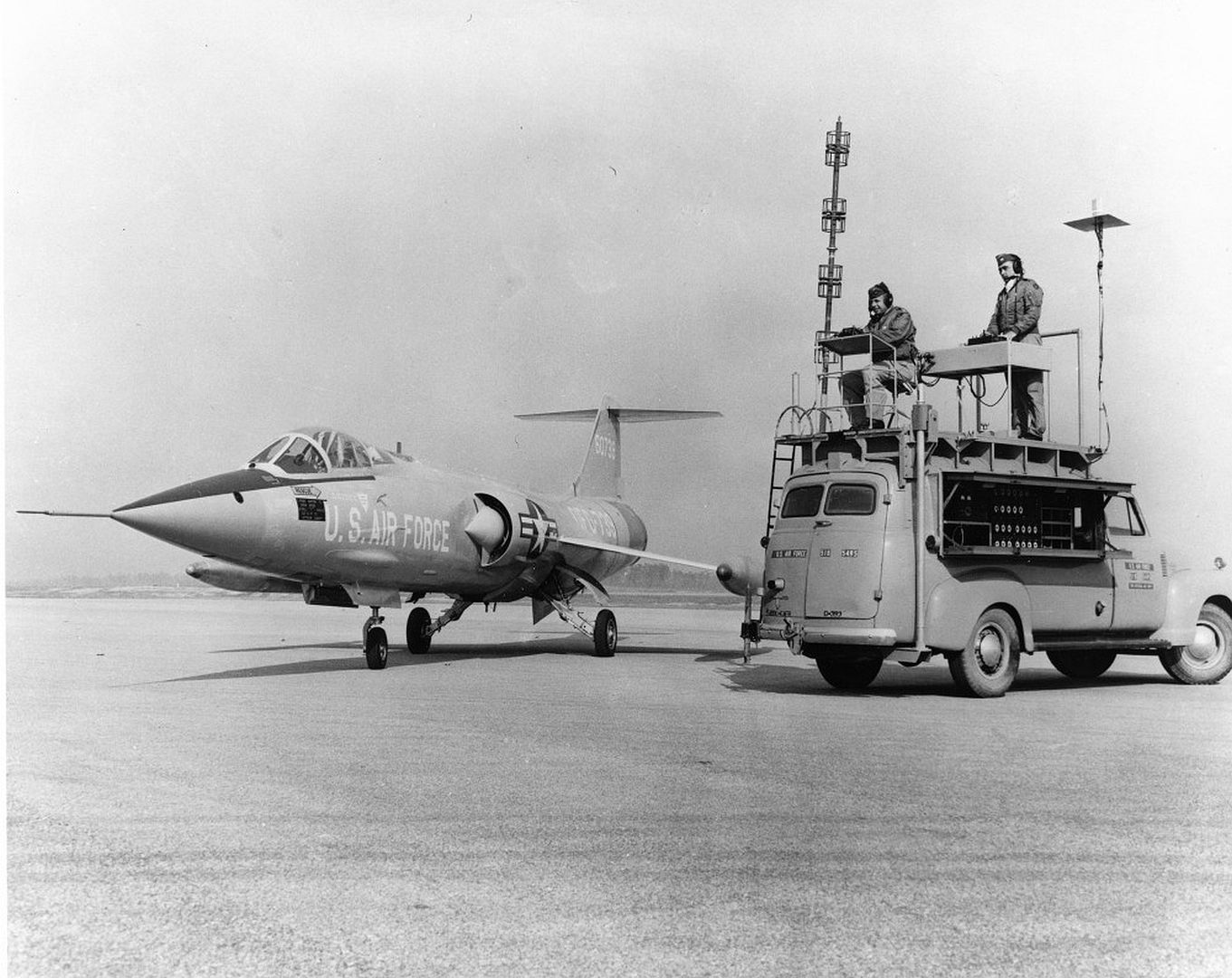

In fact, all the F-104As and F-104Bs had been relegated to US Air National Guard (USANG) service by late 1960, though they would be returned during national emergencies to USAF ADC service on occasion through the decade, being finally phased out in 1969. Some would end up in the hands of foreign air arms, and 24 of them, including a few of the YF-104As, would be converted beginning in 1960 to "QF-104A" high speed target drones. The QF-104As, painted in overall dayglo orange, were flow out of Eglin AFB in Florida and remained in service for some time. Some authors have commented that flying a demanding aircraft like the Starfighter by remote control was likely a very challenging task. The more satisfactory F-104C and F-104D would remain in first-line service longer than the F-104A, as discussed below.

The main factor in the short service life of the F-104/B in ADC service may have had something to do with its defects and limitations, but it is also unclear in hindsight why the ADC acquired it in the first place. The ADC's primary weapon was the Convair F-106 Delta Dart, a superlative aircraft that was optimized for the intercept role. The primary rationale for buying the Starfighter seems to have been to acquire experience with flying and operating the new Mach 2 aircraft coming out the end of the pipe; in other words, it was something of a neat toy to play with.

Almost as confusingly, TAC never really used the F104C/D in the fighter-bomber role, dedicating it to air superiority. Why the nuclear strike capability was added is a bit of a puzzle, though it might have been because of TAC culture, or the US Congress: TAC flew fighter-bombers and so anything they got had to be a fighter-bomber, at least on paper.

There doesn't seem to be much record of Starfighter pilots expressing any great fear or dislike of the type, as is generally the case for unpleasant aircraft. They learned the idiosyncrasies of the F-104, and the bugs were worked out; an engine upgrade program conducted by GE in the early 1960s did much to cut down the disastrous engine problems. In fact, it appears that pilots really liked flying the F-104, appreciating its blazing speed and zoom climb. In the attack role, although the Starfighter lacked the ruggedness needed to survive enemy air defenses, its tiny wing gave it a fast smooth ride at low level. It did have a notoriously wide turning radius; but some sources say that, due to the tee tail, it could turn tightly in the vertical plane, and an F-104 pilot who understood this could get on the tail of a pursuer with surprising ease.

Although marketing copy and the press liked to call the F-104 the "Manned Missile", aircrews actually called it the "Zipper" or "Zip-Four". Starfighter pilots did everything they could to master the dogfighting role and believed, with some good reason, that they could take on anyone and anything that an enemy could throw at them, and win.

* A dozen F-104As were airlifted by Douglas C-124 Globemaster cargolifters to Taiwan in October 1958 during the Quemoy-Matsu crisis in that year, but saw no action.

The Starfighter did see combat with the USAF in Vietnam. When the air war ramped up in early 1965, the US found North Vietnamese air defenses to be much more formidable than had been expected, with North Vietnamese MiGs presenting a threat to American aircraft. 28 F-104Cs were dispatched to the war theater in April 1965, where they flew from the big air base at Da Nang in South Vietnam. They were used to perform combat air patrols (CAPs) to protect EC-121 Warning Star aircraft, known to pilots as "College Eye" and later "Disco", which were radar warning system adaptations of the Lockheed Constellation four-piston airliner. A Boeing KC-135 tanker stood by to keep the F-104s in the air. The Starfighters arrived in their normal stateside natural metal finish, but were quickly given a camouflage paint job, with white on the underside and tan / dark green / olive drab disruptive patterning on top.

The Warning Stars could tip off strike packages to the whereabouts of enemy fighters, and the North Vietnamese had a strong motive to shoot them down. However, the North Vietnamese showed no inclination to want to take on the F-104s, and the Starfighters saw no action in this role. They were also put into use in the ground-attack role, mostly performing strikes "in-country" on targets in South Vietnam. It proved effective as a strike aircraft at first, and its speed and small frontal area made it a difficult target for enemy anti-aircraft gunners.

Losses occurred. An F-104C was shot down by ground fire on 22 July 1965, the pilot, Captain Roy Blakely, being killed. On 20 September 1965, Captain Phil Smith was flying a CAP over the Gulf of Tonkin at night and in murky weather. He got lost, strayed over the Chinese island of Hainan, was "bounced" by Chinese MiG-19s when he dropped out of the cloud cover to get his bearings, and was shot down. He was interned in a Chinese prison camp until 1973. Worse, two F-104Cs that went looking for him collided in the lousy weather and were lost -- though both pilots ejected safely, and were recovered.

The F-104Cs were back stateside by Christmas 1965, having in principle been replaced by the McDonnell F-4 Phantom. However, increased activity of speedy North Vietnamese MiG-21 fighters led to a reconsideration of the withdrawal of the Starfighter, and eight were sent to the air base at Udorn, Thailand, in late June 1966. The Starfighters were used to provide top cover for F-105F Wild Weasel defense suppression aircraft, looking out for MiGs while the Weasels took on air-defense sites -- but two F-104Cs were shot down by surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) on 1 August 1966, both pilots being killed.

The conclusion was that the whole idea of providing escorts for the Weasels was a bad one, since the F-105s moved fast at low level; MiGs would be hard-pressed to find them, much less catch them, and so the loss of the two pilots was senseless. The Starfighters went back to the close-support role again, but enemy air defenses were steadily getting nastier, and the losses mounted. Major Norman Schmidt, an experienced Korean War veteran, was shot down over Laos on 1 September 1966. He was taken prisoner, to die in a POW camp. On 2 October, Captain Norman Lockard was shot down by a SAM, fortunately being rescued. Captain Charles Toffert was lost over Laos on 20 October and listed as missing in action, presumed dead; that was the end of Starfighter close-support missions over Southeast Asia.

The Starfighters went back to Warning Star protection missions for a time, being fitted with a radar warning receiver (RWR) system with a prominent antenna fairing under the nose to improve survivability. However, all the Starfighters were finally withdrawn back to the States in July 1967. Keeping what amounted to a single-role type of very limited numbers in the field was becoming a logistical headache.

Although some sources indicate that the Starfighter was withdrawn from the combat theater because it was regarded as unsatisfactory, as the discussion above suggests, it wasn't quite that simple. An official document balanced the experience of the F-104 in the Vietnam war as follows: "If the Starfighter is judged against other US aircraft for its ability to sustain battle damage, to deliver heavy bomb loads or to conduct operations in bad weather, then the F-104 rates as an "also-ran". If, however, the F-104C is judged for its ability to deter MiGs, the ensure the safety of aircraft entrusted to its escort or to out-perform any aircraft in existence at the time, the "Zip-4" is unrivaled! ".

The F-104C and F-104D were phased out of first-line service in 1967, to serve with the Puerto Rican ANG into the mid-1970s. Some were passed on to foreign air forces after their retirement. -

Main AdminNF-104A ROCKET STARFIGHTER

Main AdminNF-104A ROCKET STARFIGHTER

In the early 1960s, the USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards AFB ordered three modified ex-USAF F-104As for astronaut qualification. These aircraft were stripped of combat gear, including wingtip tank capability, and were fitted with:

The larger TF-104G tailfin and a more reliable J79-GE-3B engine, with longer "double shock" intake cones.

A Rocketdyne LR121 / AR-2-NA-1 throttleable liquid-fuel rocket motor mounted at the base of the tailfin, with a maximum thrust of 27.7 kN (2,720 kgp / 6,000 lbf).

A metal nose with hydrogen peroxide reaction thrusters for pitch and yaw control at high altitude. The thrusters were arranged in pairs on the top, bottom, and sides of the nose.

A new wing with a span increased by 1.22 meters (4 feet) to 7.9 meters (25.9 feet) with twin reaction thrusters in each wingtip for high altitude roll control.

New radios and other avionics, plus a secondary hydrogen peroxide fuel system and other internal modifications.

These aircraft were delivered by Lockheed in late 1963 and were given the designation of "NF-104A". An NF-104A set a world altitude record on 15 November 1963, reaching 36,237 meters (118,860 feet), a record that was soon broken on 6 December 1963, with the NF-104A reaching meters (120,800 feet). One was then lost on 10 December 1963 during an attempt to break that record, the pilot, school commandant Colonel Chuck Yeager, ejecting successfully, though he was badly burned when his pressure suit caught fire.

Two NF-104As remained in service through the 1960s. One suffered an inflight explosion in June 1971 but the pilot brought it down safely. It was going to be retired soon anyway, so it wasn't rebuilt. The last NF-104A was retired in December 1971 and at last notice was a "gate guard" at the school.

-

6 years agoSun Jul 28 2019, 05:46pm

Main AdminFighter Training Wing

Main AdminFighter Training Wing

On 22 August 1969, the Air Force redesignated the wing as the 58th Tactical Fighter Training Wing and activated it under Tactical Air Command at Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, where it absorbed the personnel and equipment of the 4510th Combat Crew Training Wing. The wing conducted training of US, German Air Force (F-104G), and other friendly foreign nation aircrew and support personnel, and participated in numerous operations and tactical exercises while operating Luke until April 1977. It managed Tactical Air Command's Central Instructor School from 1971?1981. Beginning in early 1983 it performed tactical fighter training for US and foreign aircrews in the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.

-

6 years agoSun Nov 05 2023, 11:12amDuggy

Main AdminGerman Starfighters

Main AdminGerman Starfighters

The Germans were the first foreign buyer of the Starfighter and, at least in terms of numbers obtained, the most enthusiastic user of the type. They received an initial batch of 30 "F-104F" trainers from Lockheed in late 1959. These were more or less F-104Ds, fitted with the uprated J79-GE-11A engine plus simplified avionics, and were to be used in principle to get the Luftwaffe up to speed on the Starfighter. They were retired in 1972.

The Germans then obtained 605 F-104Gs, 145 RF-104Gs, and 137 TF-104Gs, replacing F-86s and F-84s / RF-84s. The order was so huge that it soaked up all of the production of the Messerschmitt-led group, and took production from the other F-104G manufacturing groups as well. German F-104Gs featured the F15A-41B version of the NASARR radar, with navigation, bombing, and air-to-air modes. Navigation and bombing modes featured ground-mapping, terrain following, and ranging, while air-to-air modes included search and targeting for Sidewinder AAMs and the Vulcan cannon. Most other F-104Gs used by other nations would feature the similar F15AM-11 variant of the radar.

The primary weapon of the Luftwaffe F-104G in the tactical strike role was the B43 nuclear munition. This was a weapon in the 1-megaton range, mighty powerful for tactical strike, bringing up the Cold War saying that "a tactical nuclear weapon is one that goes off in Germany." Although West Germany was formally a non-nuclear nation, it did have a nuclear capability through a cooperative arrangement with the US, with the US supplying the weapon and retaining control over it through a dual-command arrangement involving American officers attached to the Luftwaffe. Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy also used their Starfighters to carry the B43 munition under a similar dual-command arrangement. However, tactical Starfighters also carried conventional stores, such as iron bombs, cluster munitions, and unguided rocket pods.

Some of the German RF-104Gs were later converted to F-104G standard. Lockheed also offered the Germans a more sophisticated reconnaissance variant, the "RTF-104G1" with imaging radar and infrared sensors as well as cameras, but the Germans obtained the RF-4E Phantom instead.

* The German naval air arm, the Marineflieger, operated a total of 146 F-104Gs and 27 RF-104Gs, these numbers being included in the total German buy given above. The Marineflieger's main need had been to replace British Hawker Sea Hawk fighters. The service had wanted to obtain the F-4 Phantom or the British Blackburn Buccaneer, but commonality with the Luftwaffe won out.

Marineflieger F-104Gs operated in the anti-ship role, originally carrying two French AS-30 missiles, comparable to the US Bullpup, being guided by "eyeball" over a radio link. These were somewhat ineffective weapons, being replaced by the much superior AS-34 Kormoran from 1977. The Kormoran was an optimized anti-ship missile, with its own radar seeker and "fire and forget" capability.

Marineflieger RF-104Gs were built to a special standard, with long-range cameras mounted in a bay behind the cockpit shooting out windows in the sides of the fuselage. They retained the trimetrogon camera arrangement in the belly. They were often used to observe shipping and harbor activity in the Baltic, remaining over international waters and taking shots with the side-looking cameras.

Luftwaffe Starfighters were delivered in natural metal, though their wings were painted white to emphasize the Luftwaffe cross. In the mid-1960s, a camouflage scheme was introduced, with dark gray and dark green in a disruptive pattern on top and medium gray underneath. This led to a similar pattern with light gray underneath, finally progressing in the 1980s to a wraparound dark gray / dark green / olive drab disruptive pattern. Marineflieger F-104s were painted dark slate gray on top and medium gray underneath. Custom paint jobs were occasionally applied for special occasions, such as a Starfighter given a paint job in black / red / yellow German national colors.

The Luftwaffe found the Starfighter a real handful, and the Germans would suffer a large number of accidents. A popular joke among Germans at the time was that anyone who wanted to get a Starfighter should just buy a farm and wait for one to crash onto it. Few were really laughing, however, since about 110 Luftwaffe pilots were killed in Starfighters; the accident rate would lead to a major public outcry and a long-running political controversy. Since many of the fatalities were from ejections at low level with the C2 ejection seat, beginning in 1967 the entire fleet was refitted with the Martin Baker Mark 7 zero-zero ejection seat.

Much of the problem was the relative lack of experience of Luftwaffe maintenance and flight crews. One of the issues was that flight familiarization with the Starfighter was performed with Luftwaffe machines at Luke Air Force Base in the sunny state of Arizona, which gave the pilots plenty of open space to fly around in, but did not prepare them well for much murkier German weather. Underlying the problem was the fact that the arrival of the German Starfighter force meant a major expansion of the Luftwaffe, and growing an organization can lead to wide range of problems. It should be noted that the Luftwaffe's accident rate with the F-84 / RF-84 had been as bad or worse.

German Starfighters were finally retired in the mid-1980s, being replaced by the Panavia Tornado and the F-4 Phantom, lingering on in specialized roles into the early 1990s. Many of the survivors were passed on to other air arms. Total losses were 270 aircraft, or about 30% of the force. Other air forces had higher loss rates, but the Luftwaffe was by far the biggest operator of the Starfighter, and so had the highest absolute number of losses. After the F-104, the Germans would have a strong aversion to single-engine fighter aircraft.

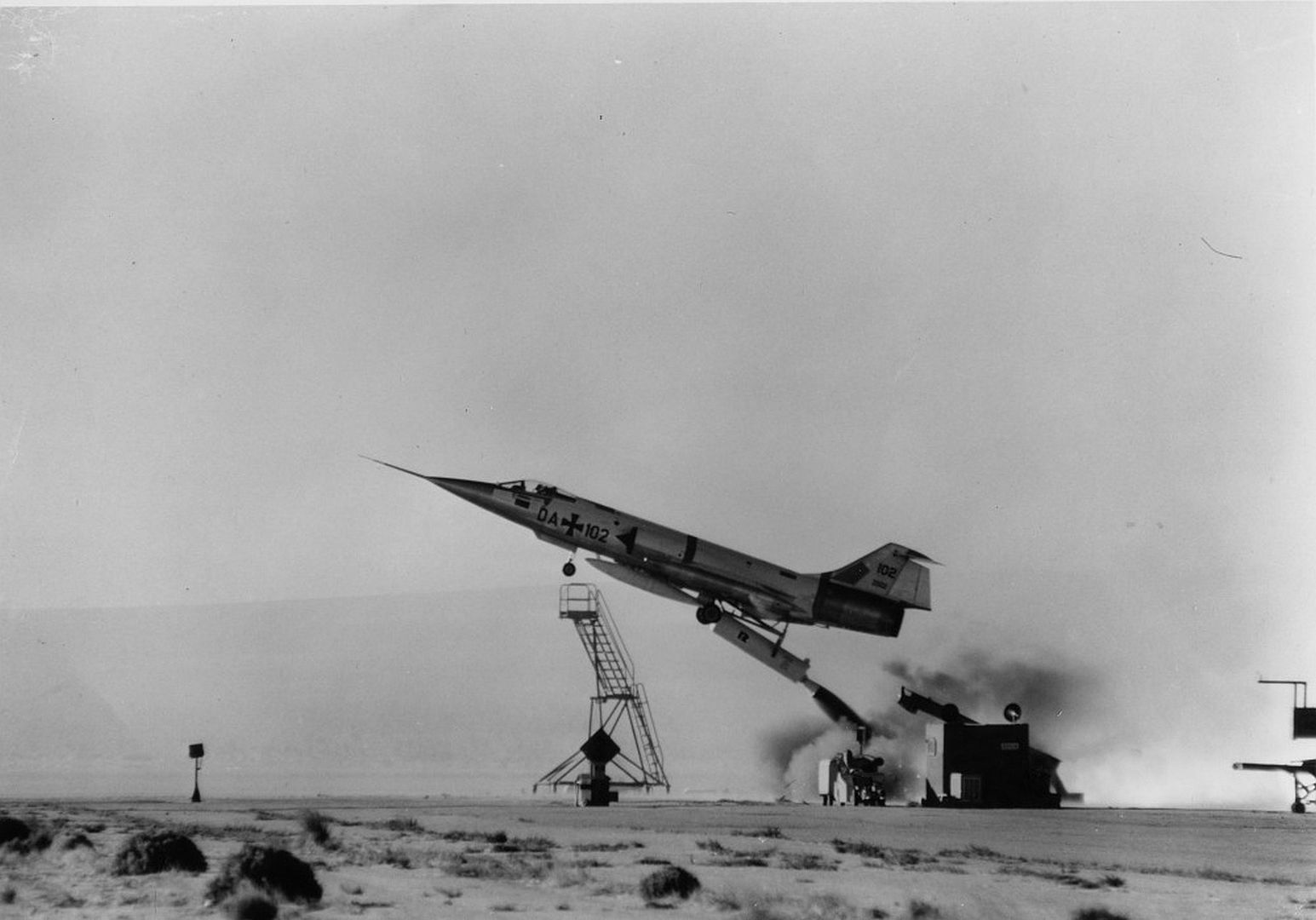

As a footnote to German service, in the early days Luftwaffe Starfighter operations there was a worry about the vulnerability of airfields to a first strike, and a number of concepts were explored to find ways of getting around the problem. One exercise involved trials using three F-104Gs fitted with catapult gear and arresting hooks so they could be launched by a catapult system from a short airfield. The program was designated "Short Airfield for Tactical Support (SATS)".

A more drastic approach was to use "zero length launch (ZELL)" with the F-104G, blasting the aircraft off a trailer or out of a hard shelter using a big solid-fuel booster rocket. The US had already developed the technology to launch F-100 Super Sabres and the gear was modified for the F-104G, with the a series of ZELL tests in 1963. The test program went very well, with test pilots commenting on how straightforward and smooth the ZELL shots were. However, neither SATS nor ZELL were fielded.

Much later, in the 1970s, the German firm Messerschmitt-Boelkow-Blohm (MBB), a late-1960s consolidation of German aircraft manufacturers, modified an F-104G to perform experiments on the merits of "dynamically unstable" aircraft, meaning machines that would be impossible to control if they didn't have an electronic "fly-by-wire (FBW)" flight control system to keep an eye on what was going on at all times and adjusting flight trim accordingly. The modified Starfighter, known as the "F-104CCV" for "Control Configured Vehicle" performed its first flight in 1977.

The kit for the electronic FBW system was housed in bulges on each side of the top of fuselage near the rear of the wing. The aircraft was gradually ballasted to shift its center of gravity and increase its instability, and then in 1980 was flown with a canard flight surface, actually a standard F-104 tailplane tacked on to the forward fuselage, to increase the instability of the aircraft. The test program ended in 1984, with the aircraft ending up in a museum.

-

6 years agoSun Nov 05 2023, 11:12amDuggy

Main AdminDutch Starfighters

Main AdminDutch Starfighters

The Netherlands was another major European Starfighter user, with the type going into service to replace the F-84 / RF-84, as well as Lockheed RT-33s. The Dutch acquired 95 F-104Gs, 25 RF-104Gs, and 18 TF-104Gs from Fokker, Fiat, and Lockheed production. That gave a total of 120 single-seaters and 18 two-seaters, or 135 aircraft in all. Dutch RF-104Gs did not have the trimetrogon camera system, instead being fitted with the NVOI Orpheus centerline reconnaissance pod, with five TA-8M film cameras and an infrared linescan unit.

Dutch Starfighters were delivered in overall anti-corrosion gray colors, but were given the standard NATO camouflage of a dark gray / dark green disruptive pattern on top and medium gray underneath. These machines served into the mid-1980s, being ultimately replaced by the F-16. Some of the survivors were passed on to Greece and Turkey. The Dutch lost a total of 43 Starfighters from accidents, a painful attrition rate of 35.8%.

-

Main AdminBelgian Starfighters

Main AdminBelgian Starfighters

Belgium obtained 101 F-104Gs from SABCA production and 12 TF-104Gs from Lockheed production, with deliveries from 1963 through 1965. It appears that one of the F-104Gs was Lockheed-built as a pattern aircraft, to be torn down and reassembled by SABCA.

Belgian Starfighters were originally flown in natural metal but were later painted in a camouflage scheme, with light gray on the bottom and a disruptive pattern of olive drab / dark green / tan on top. The last Belgian F-104s were phased out of service in 1983, being replaced by the F-16. The Belgians lost 41 of their Starfighters in accidents, an even more painful attrition rate of about 37%.

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources