Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Operation Firefly

Operation Firefly

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

4 years agoSun Apr 18 2021, 07:11pmDuggy

Main AdminThe 555th was formed in November 1943 as an all-black Army paratroop unit at Fort Benning, Georgia under the command of 1st Lt. James H. Porter. It was expanded to full battalion size November 1944 at Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

Main AdminThe 555th was formed in November 1943 as an all-black Army paratroop unit at Fort Benning, Georgia under the command of 1st Lt. James H. Porter. It was expanded to full battalion size November 1944 at Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

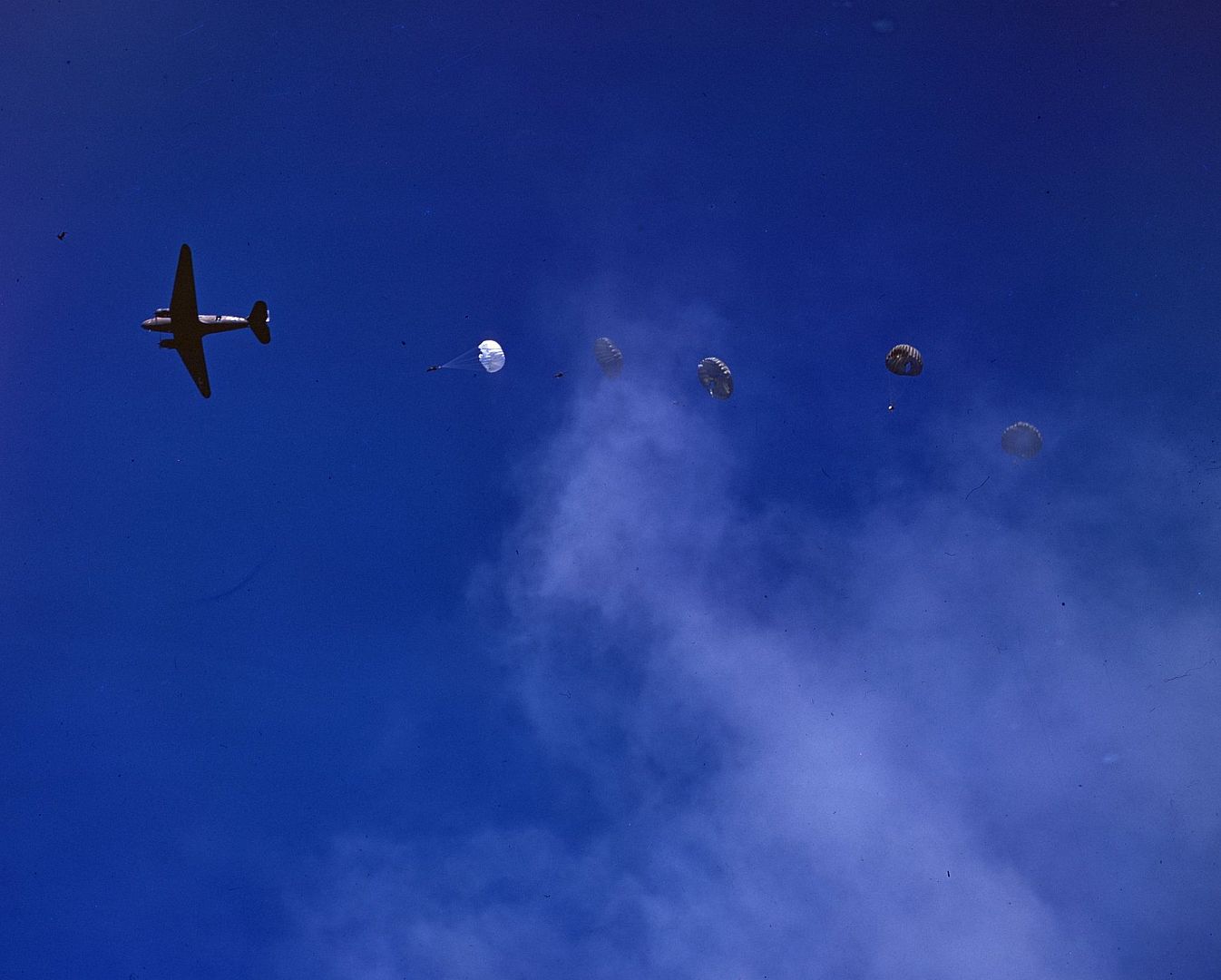

In April 1945 the 555th was assigned as a 300-man smokejumper Component of a larger 2,700 person military effort group assigned to Operation Fire Fly in US Forest Service regions 1,4,5, and 6. Fire Fly was organized as a massive civilian/military effort to combat the expected wildland fire threat from the Japanese balloon bombs, which had been arriving in increasing numbers along the west coast (and as far east as Michigan) since August 1944. Although it was not public knowledge at the time, there was serious concern by US officials that the balloon bombs would also introduce biological warfare agents into North America.

In its assigned smokejumper role, the 555th was based primarily at Pendleton, Oregon and Chico, California. The 555th also made jumps from other temporary bases. During its Fire Fly assignment April-October 1945, the 555th made 1,200 jumps and helped suppress 36 fires. The 555th was deactivated on December 9, 1947, and most of its remaining personnel were reassigned to the 82nd Airborne Division.

The first recorded intercontinental weapons were the more than 9,000 paper balloon bombs launched from the main Japanese island of Honshu from November 1944 through April of 1945. Although 1,000 of these balloons reached North America, only 342 were ever sighted or found. Some of those that reached North America, but are not yet found, could conceivably surprise or injure future discoverers.

Although the Japanese army began experimentation with unmanned balloon borne weapons as early as 1933, the Japanese military did not actively pursue this program until Spring 1942. Military historians believe the surprise air raid on Tokyo, led by Lt. Col. Doolittle, may have been one of the reasons for the Japanese renewed interest in the balloon program. With most of the Japanese military committed to their campaigns in mainland Asia and the South Pacific, the unmanned balloon program was revived as a possible retaliation weapon against North America. The reborn army balloon program was code-named FUGO, an acronym which means "a wind ship weapon".

The army originally decided to prepare 100 balloons to be launched from submarines a few miles from the North American coast. The navy refused to tie up submarines to launch army balloons, resulting in the command decision to launch from the Japanese islands. Although the Japanese had studied high-altitude winds for many years, including their careful application of data from Russian experiments, it was not definitively known in 1942 just what altitude would be best to carry balloons from Japan to North America. Here it should be noted that in 1942 Japanese knowledge of these high-altitude west-to-east winds, later to become known as the jet stream, was far more advanced than the allies.

In order to determine the most effective altitude for balloon transport, the navy launched 40 silk/rubber (type balloons beginning in February 1944. None of these carried weapons, but all carried radiosonde units which measured air temperature, barometric pressure, etc. Three of these navy Type B unarmed weather balloons were eventually recovered in or near North America. From that data, the Japanese determined that the best altitude for balloon transport was 30,000 feet and the average flight time to North America was about three days.

balloons beginning in February 1944. None of these carried weapons, but all carried radiosonde units which measured air temperature, barometric pressure, etc. Three of these navy Type B unarmed weather balloons were eventually recovered in or near North America. From that data, the Japanese determined that the best altitude for balloon transport was 30,000 feet and the average flight time to North America was about three days.

This led to the army design of a slightly larger (10 meter diameter) paper balloon which included both explosive and incendiary devices. The weapons and ballast were carried around the perimeter of a horizontally suspended wagon-wheel like structure which was carried below the body of the paper balloon.

The balloon carried enough sandbags so that when they had all dropped, the balloon should be over North America. The barometer device then began to drop four incendiaries, one at a time, as it blew generally eastward across North America. The last weapon in the series was an explosive anti-personnel bomb. After all the weapons had been dropped, a small explosive/incendiary charge was supposed to destroy the balloon mechanism and paper bag, leaving practically no evidence of its presence.

More than 9,000 of the army Type A paper balloon weapons were launched from Honshu between November 1944 and April 1945. These balloons were recovered in North America from Alaska to Mexico, and as far east as Michigan. Forty-five were recovered in Oregon, the most in North America. In all, 342 were eventually sighted or recovered in North America.

The intent of the balloon program was to start massive forest fires in North America. However, the timing of the launches from November through April (believed to be the time of the most favorable high-altitude winds) was winter, so the net result was only one recorded fire, ironically caused by a balloon-induced arcing power line at then supersecret atomic works at Hanford, Washington.

The only WWII fatalities from enemy action on the mainland North America sadly occurred May 5, 1945, near Bly, Oregon, when a family encountered one of the explosive bombs from a balloon. The resulting explosion killed six people.

Why did the Japanese stop their balloon launches in April 1945 just as North American fire season was about to start? A combination of factors; Somehow, the allied authorities in North America had persuaded the free press NOT to publish news of the balloon attacks. With a few relatively minor exceptions there were no published or broadcast accounts of the balloon attacks, which were actually all too well known and of great concern to allied military and civilian authorities. The Japanese did not believe our authorities could actually silence our free press, and therefore thought, no news must mean no significant results from the balloon attacks.

Another major factor in the Japanese decision to discontinue the balloon attacks was the damage to Japanese industry from U.S. air raids on Japan. Also, the hydrogen gas needed for the balloon program became scarce due to bomb damage to gas plants.

Allied authorities were extremely concerned over the potential for major damage from balloon attacks. The fire potential was to be dealt with in the U.S. through a sizeable military supplement known as Operation Fire Fly to the regular civilian firefighting force, which was much reduced by other wartime demands.

Perhaps the major allied concern was for the potential for biological warfare from balloon borne organisms. Fortunately, this did not occur, but another sizeable allied effort was mounted to monitor potential disease outbreaks.

A little-known and seldom reported variation on the WWII balloon attacks was a British effort to launch balloon weapons against German-occupied Europe. The British discontinued their balloon attacks when some of their balloons came down in neutral Sweden.

In the end, the Japanese balloon attacks were of little strategic significance. They did offer the potential for widespread damage from fire and biological weapons, and they tied up considerable allied effort that might have been assigned elsewhere. They were the first intercontinental weapons.

Text from here - https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/fire/people-working-fire/smokejumpers/smokejumper-base-contact-information/missoula-smokejumpers/history/operation

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources