Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Northrop XB-35/YB-49/YRB-49A

Northrop XB-35/YB-49/YRB-49A

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

3 years agoSun Dec 17 2023, 10:12amDuggy

Main AdminXB-35

Main AdminXB-35

John K. Northrop was one of the pioneering giants in aviation. He got his start in aviation back in 1916, when he went to work for the Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company. Jack Northrop joined Douglas Aircraft in 1923, and rose to the rank of chief engineer, but he later left Douglas to rejoin his old team at what was now known as Lockheed. While there, he worked on the Lockheed Vega monoplane. In 1928, Northrop helped found the Avion Corporation, which built the well known Alpha monoplane. However, in 1930 he was forced to sell Avion to the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation.

At the height of the Depression in 1932, with partial financing from the Douglas Aircraft Company, Jack Northrop founded the first aircraft company bearing his name. His company built the famous Gamma and Delta monoplanes which were so successful during the 1930s. However, in August of 1939, Jack Northrop left the company he had founded, since by that time it had become just another division of Douglas, and founded an entirely new and completely independent company named Northrop Aircraft, Inc at Hawthorne, California.

As early as 1923, Jack Northrop had been convinced that the flying wing, in which the aircraft carried all loads and controls within the wing and dispensed with fuselage and tail sections, was the next major step forward in aircraft design. In support of the flying wing idea, Jack Northrop had built a number of small-scale demonstrators to evaluate the concept. One of these was the N1M flying wing demonstrator which flew for the first time on July 3, 1940.

On April 11, 1941, the USAAF issued a request for proposals for a high-altitude bomber that could carry a 10,000-pound bombload halfway across a 10,000 mile range. Maximum speed was to be 450 mph at 25,000 feet, cruising speed 275 mph, service ceiling 45,000 feet, and a maximum range of 12,000 miles at 25,000 feet. Invitations for preliminary design studies were sent to the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation and to the Boeing Airplane Company. The Consolidated submission was eventually to emerge as the B-36. As part of this project, Northrop was contacted on May 27, 1941 and asked to provide studies of a flying wing proposal as it related to requirements for a range of 8000 miles at 25,000 feet with one ton of bombs, a cruising speed of 250 mph, a service ceiling of 40,000 feet, and a bombload of 10,000 pounds, which were much less demanding than those of the April ll RFP.

In August of 1941, slightly more ambitious requirements were again submitted to Northrop. The flying wing bomber project (designated NS-9 by the company) received approval for an initial start from the USAAC in September of 1941, following a visit to the Northrop plant by Assistant Secretary of War Robert Leavitt, General Henry H. Arnold, and Major General Oliver P. Echols. The order was confirmed on October 30, 1941. The contract included a purchase order for engineering data, model tests, plus a 1/3-scale flying mockup known as the N9M. On November 22, a contract for a single XB-35 prototype and an option for a second was signed. The option for the second XB-35 was exercised on January 2, 1942. According to the terms of the contract, the first XB-35 was to be delivered in November 1943, with the second following in April of 1944.

Detailed design work on the XB-35 began in early 1942, and the XB-35 full-scale mock-up was approved on July 5, 1942. On December 17, 1942, 13 YB-35 service test aircraft were ordered.

Two more N-9M flying scale models were ordered in early 1943, with a fourth being ordered in mid-1943.

The advantages of a flying wing format were perceived as providing both low drag and high lift, which meant that the XB-35 could carry any weight faster, farther, and cheaper than conventional aircraft. In addition, the use of a flying wing meant that simpler construction methods could be used with fewer structural complications. A flying wing should cost less to build since it was built as a single unit with no added tail or fuselage. A flying wing provides a better weight distribution for the offensive load, since compartments along the entire span could distribute the weight of the bomb load much more evenly. Finally, a flying wing presented a smaller target when seen from fore, aft, or from the side when engaged in either offensive or defensive operations.

Northrop lacked adequate production facilities for the manufacture of production B-35s, and enlarging the company's Hawthorne plant was out of the question at that time. At the end of 1942, in search of more production facilities, Northrop began negotiating with the Glenn L. Martin Company. Northrop management indicated that they would be satisfied to fabricate only the XB-35s and the YB-35s, with Martin having the responsibility for building the production B-35s at its plant in Baltimore, Maryland. A contract for 200 B-35s was initially planned in November of 1942, and was formally issued on June 30, 1943. The first production B-35 was to be delivered by June of 1945.

In support of the program, Northrop built four 60-foot wingspan (about one-third the size of the proposed B-35) N9M flying wing test aircraft to train pilots in handling flying-wing aircraft and to see if the general concept was feasible. They were of mixed wood and metal construction, with the center section being of welded steel tubing. The covering was of wood and metal panels, with the outer wing panels being of wood with metal wing slots and wing tips. The four N9Ms were later called N9M-1, N9M-2, N9M-A, and N9M-B respectively. They were initially powered by a pair of 290 hp Menasco C65-4 six-cylinder air-cooled engines each driving a pusher two-bladed propeller by means of an extension shaft via a fluid-drive coupler. The engines were cooled by air admitted by large under-wing scoops. The N9M-B was later fitted with two air-cooled 400 hp Franklin engines. Provisions were made for a pilot and one passenger, both housed underneath a single transparent bubble canopy. It was provided with a retractable tricycle landing gear, and a rear outrigger tail wheel was fitted. These 4 aircraft flew with neither civil registrations nor military serials. The design details worked out in the N9M were incorporated into the design of the XB-35.

The first N-9M flew for the first time on December 27, 1942. It crashed on May 19, 1943, killing its pilot. On the maiden flight of the second model on June 24, 1943, the cockpit canopy of the aircraft flew off while in flight, but the pilot was able to land successfully. Nearly all the flight tests of the N-9M were shortened by mechanical failures of one kind or another, particular with failures in the Menasco engines. The fourth and last N9M (the N9M-B) flew for the first time on September 21, 1943.

The N9M-B (the last of the four) managed to survive all these years, and was restored to flying condition over a period of 12 years by volunteers at the Chino 'Planes of Fame Museum' and flew again, for the first time after about 45 years, on November 11, 1994. The new civil registration of the N9M-B is 'N9MB'.

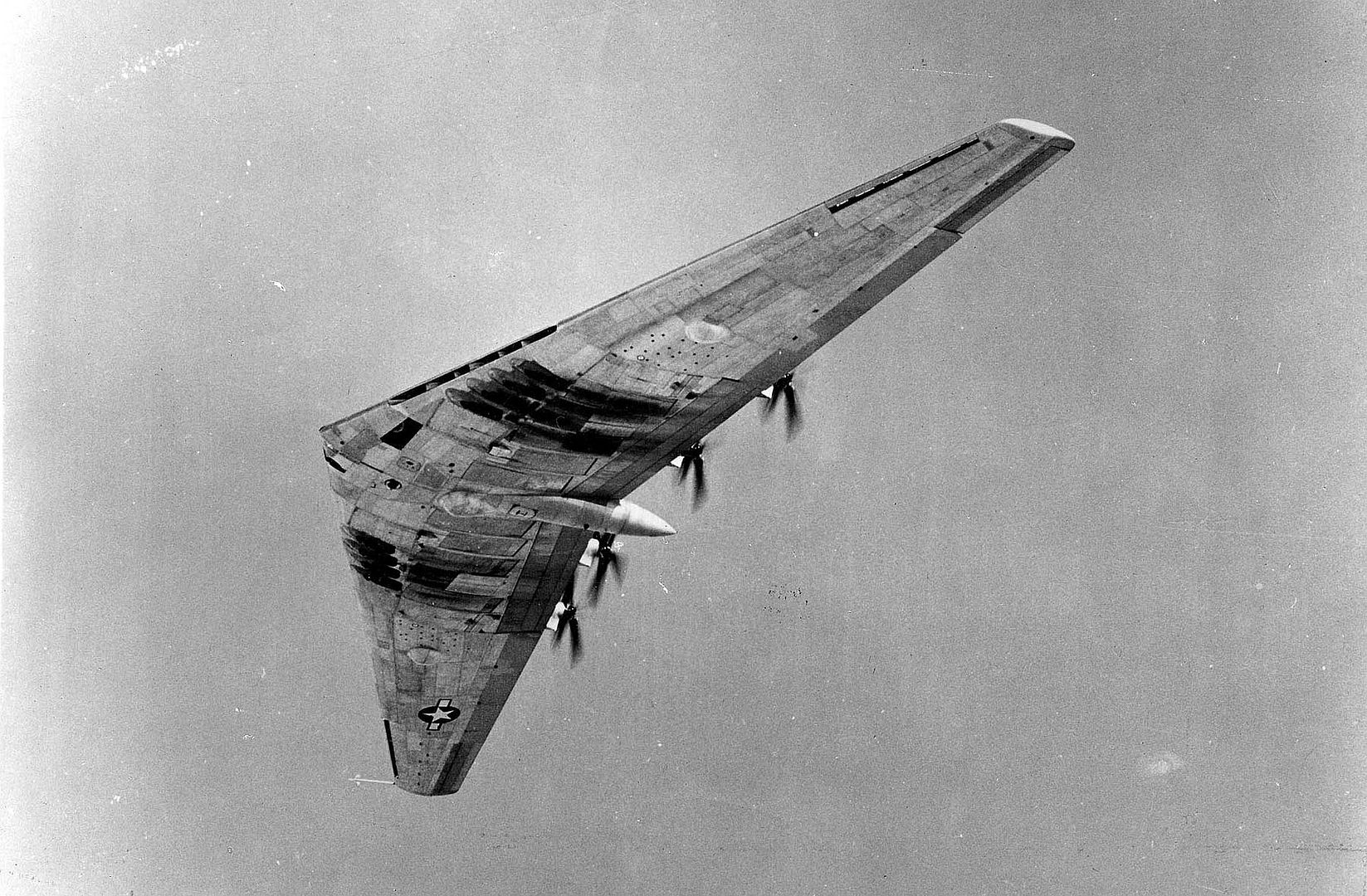

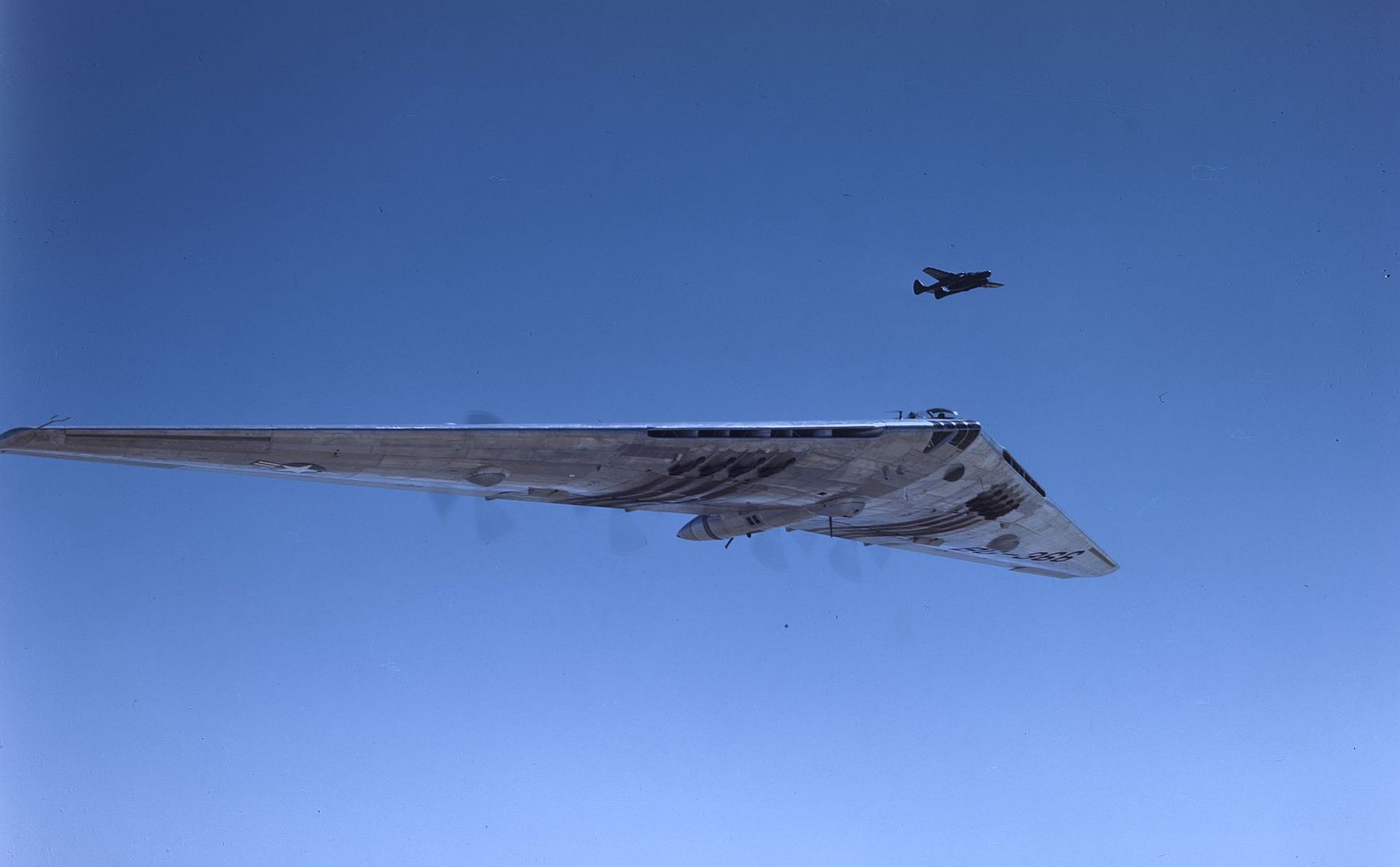

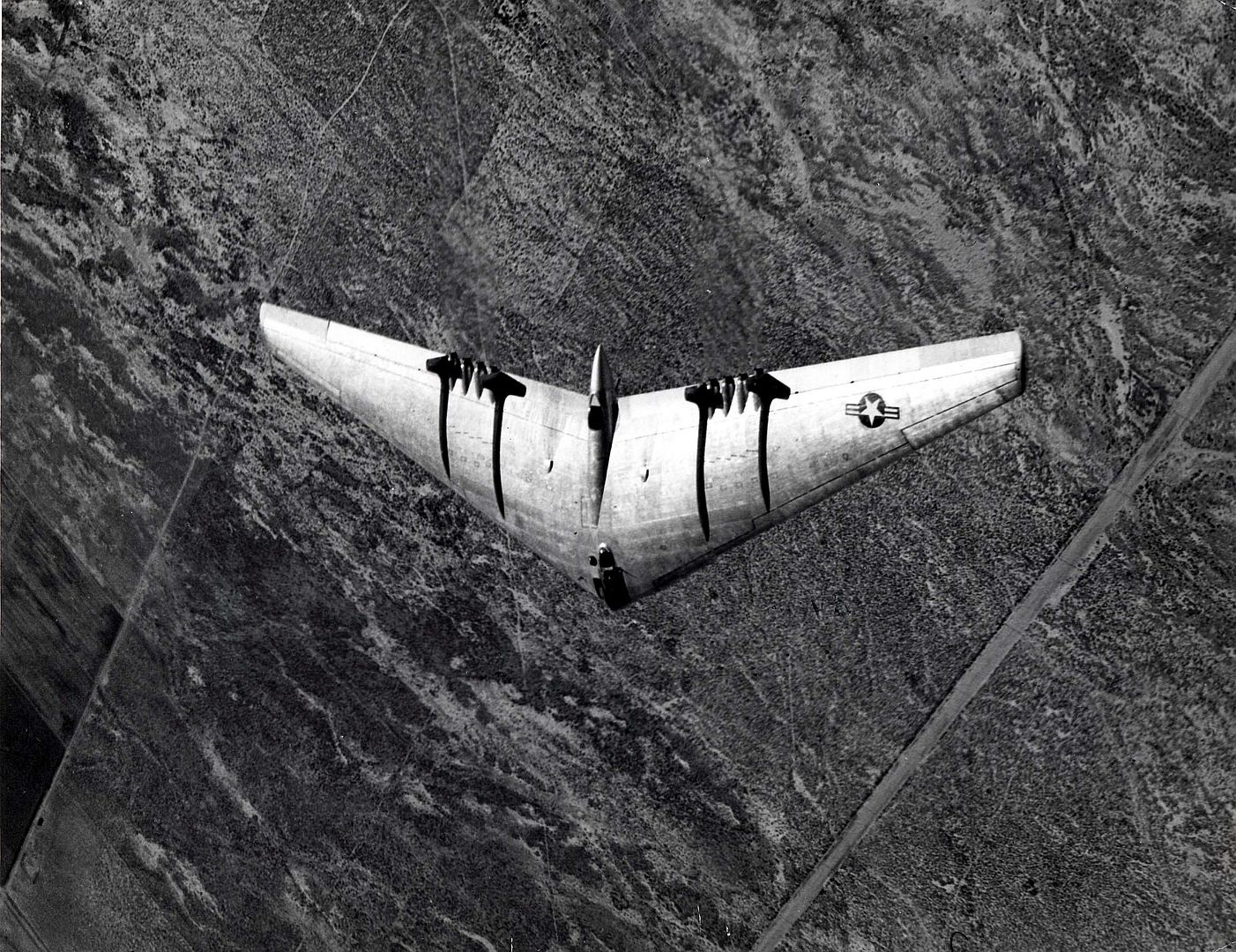

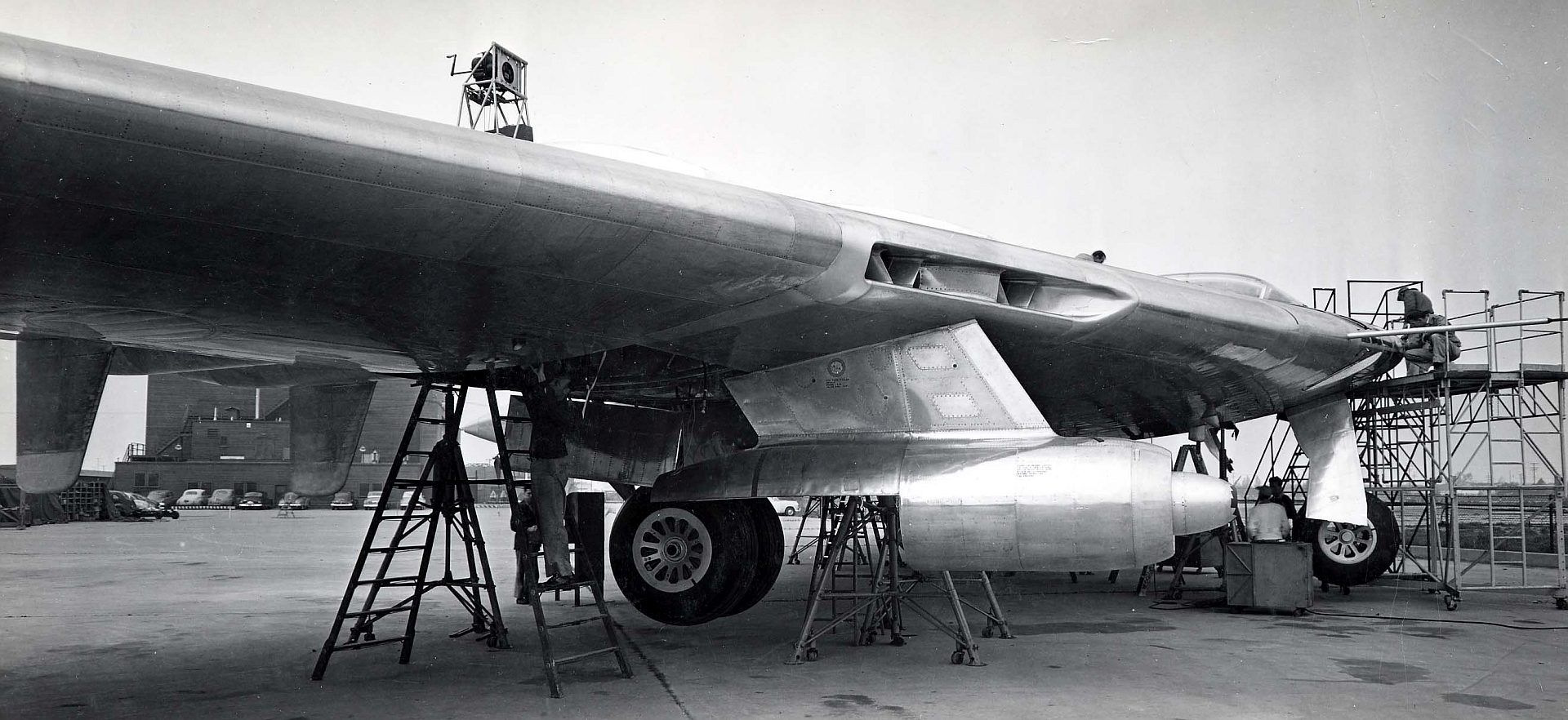

The wingspan of the B-35 was 172 feet, and the leading edges were swept back at an angle of 27 degrees. The wing of the B-35 was 37 1/2 feet wide at the center, tapering to 9 feet wide at the tips. Because of the wing sweep, the overall length of the aircraft was slightly over 53 feet.

The lateral control that was normally provided by conventional rudders was provided on the B-35 by a set of double split flaps located on the trailing edges of the wingtips. These operated by having the split flaps open up in butterfly fashion to provide a braking effect. When the left rudder pedal was depressed, the left flaps would open up, forcing a turn to the left. If both pedals were depressed, both split flaps would open up to increase the gliding angle or reduce the air speed. These double split flaps could also act as trim flaps, and could be adjusted as a unit either up or down to trim the airplane longitudinally.

Elevons were located along the trailing edge of each wing inboard of the trim flaps. When deflected together in the same direction (by the pilot moving the control column fore or aft), they could cause the airplane to descend or climb. When operated differentially (by having the pilot move the control wheel left or right), they caused the airplane to bank left or right in a fashion similar to the function of conventional ailerons. For landings and takeoffs, A set of flaps were located in the wing trailing edge near the center.

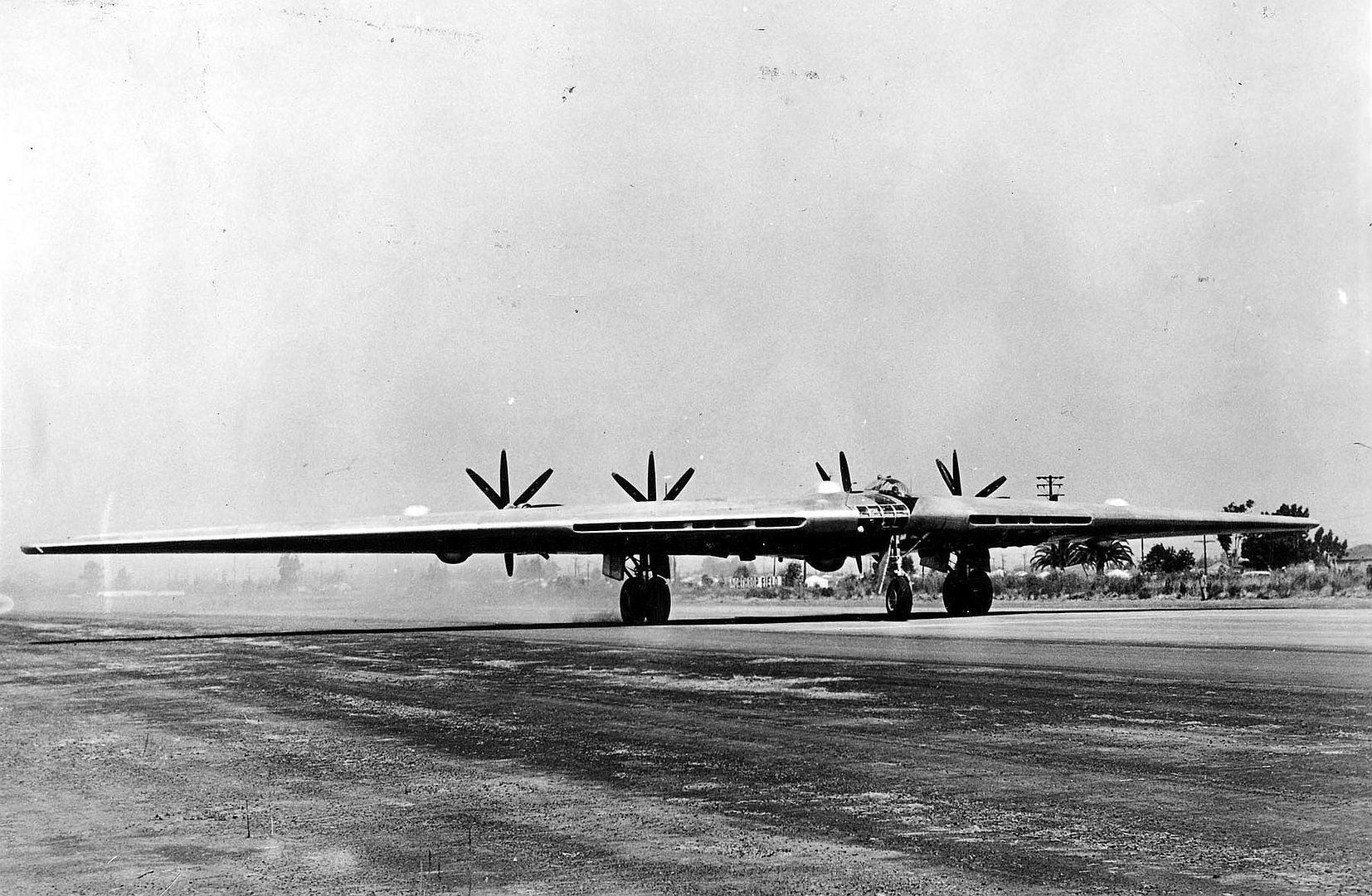

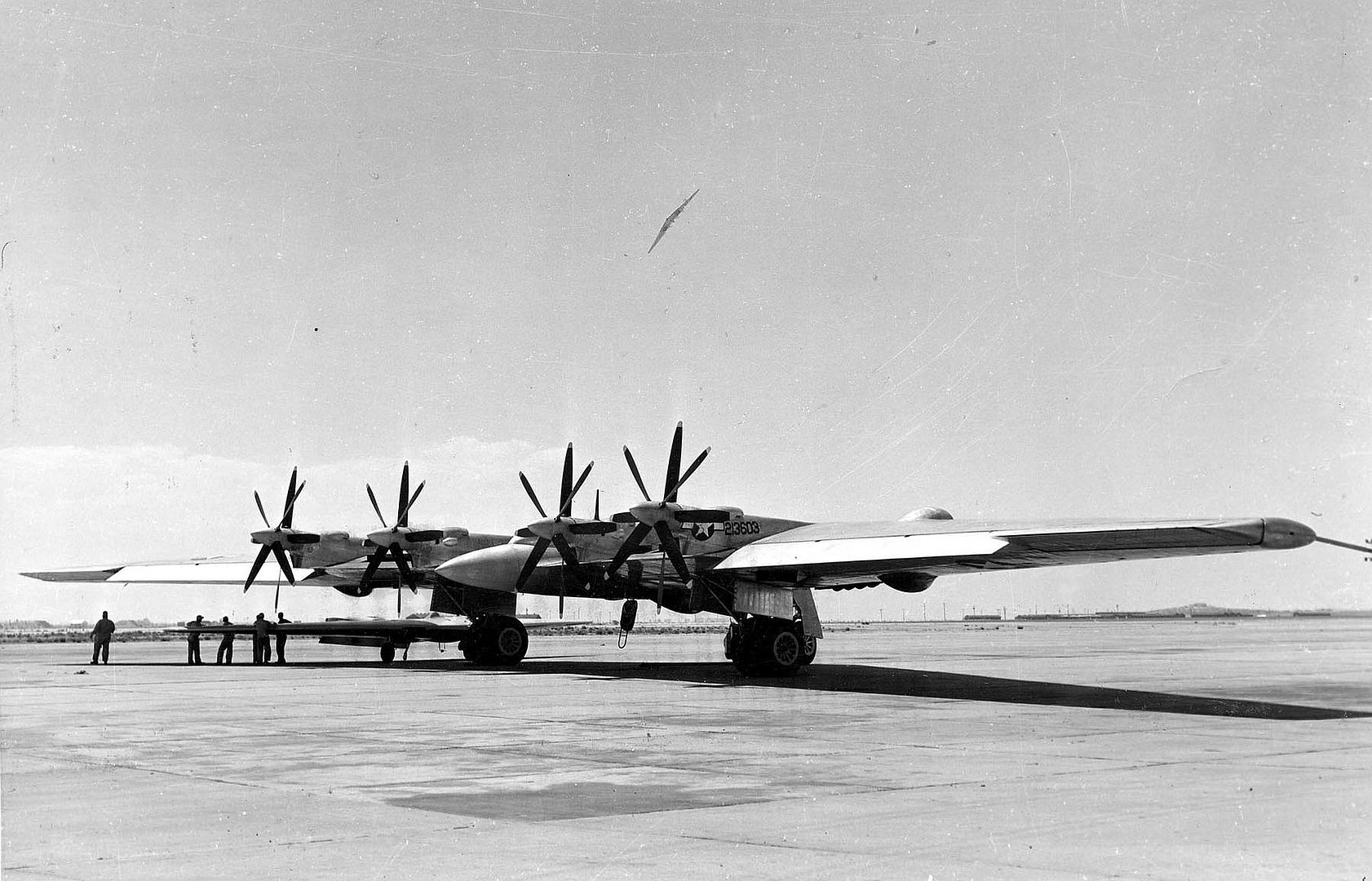

The aircraft was powered by four Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major air-cooled radials (two R-4360-17s and two R-4360-21s) with double superchargers and feed by cooling air coming from long slots cut into the wing leading edge. Each engine drove a set of coaxial, counter-rotating four-bladed pusher propellers mounted at the end of a driveshaft that protruded beyond the trailing edge of the upper wing surface.

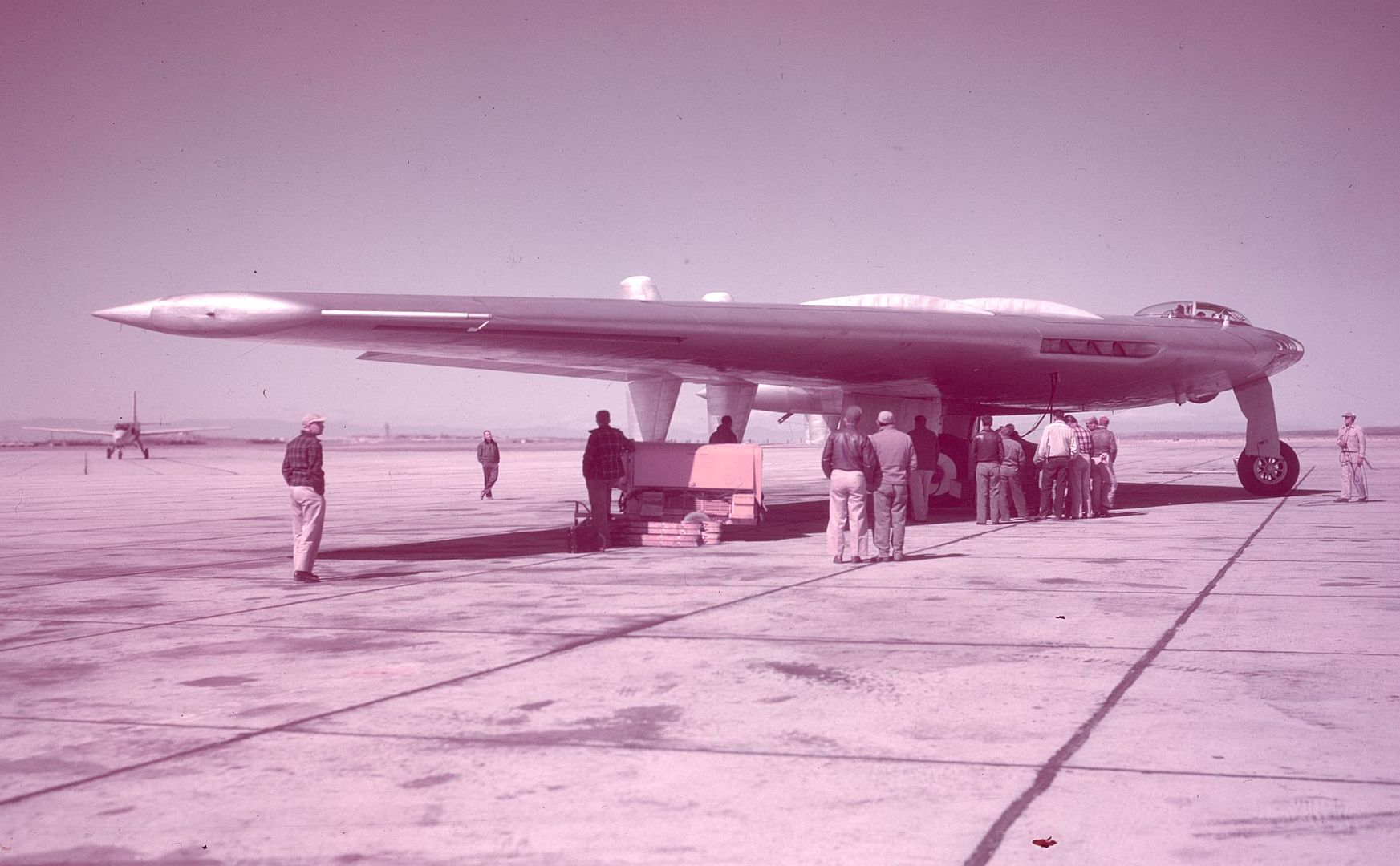

The B-35 was 20 feet tall when sitting on its tricycle landing gear. 5' 6" dual wheels on the main gear and a 4'8" wheel on the nose gear.

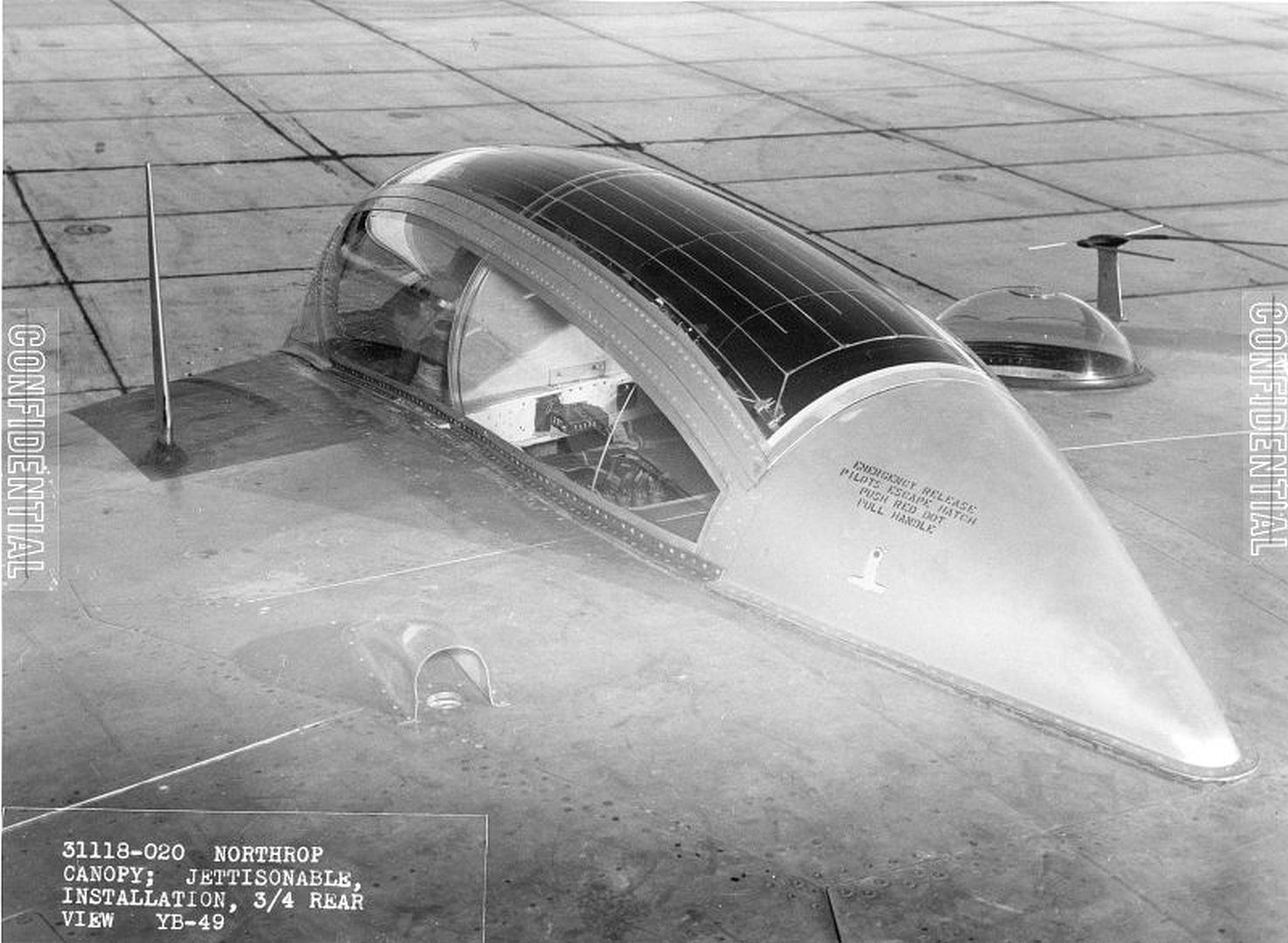

The crew of the XB-35 was carried in a crew cabin installed at the center of the wing, with a tailcone protruding beyond the central wing trailing edge. The normal crew was 9--a pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, engineer, radio operator and 3 gunners. The pilot sat in the very front of the wing center section (slightly offset to the left of center) underneath a transparent bubble-type canopy. The copilot sat to the right of the pilot and somewhat lower down, and sighted through a set of transparent windows cut into the front of the wing. His visibility, though, was fairly marginal. The bombardier's station was located to the right of the copilot's seat, and the bombardier operated the bombsight by aiming it through a square window cut into the forward underwing surface. The navigator and flight engineer sat to the rear of the copilot. The navigator had a small transparent bubble over his seat for the sighting of stars. Six more crew members could be added as substitutes on long-range missions, with folding bunks in the rear of the crew cabin to accommodate the off-duty crewmen.

The defensive armament was to consist of a set of remotely-controlled barbettes. A quartet of 0.50-inch machine guns were housed inside each of dorsal and ventral barbettes that were mounted on the tailcone along the wing's centerline. Four 0.50-inch machine guns were installed in the rear of the tailcone. A pair of 0.50-in machine guns were installed in each of four barbettes mounted on the wing outboard of the outermost engines, one above and one below the wing. The guns were remotely sighted by gunners sitting in stations in a bubble in the upper rear part of the tailcone, in a ventral station, and in a position in the pilot's bubble immediately behind the pilot's seat. The bombs were carried internally in eight individual bomb bays cut into the under surface of the wing outboard of the main crew cabin.

The XB-35 was built of an entirely new aluminum alloy developed by Alcoa. This alloy was considerably stronger than previous metals. The fuel was carried in self-sealing leak-proof fuel cells in the wing, and additional fuel could be carried in tanks in the bomb bay and in other wing compartment areas.

Unfortunately, by early 1944, the B-35 program was seriously behind schedule. Test results with the N-9M aircraft had indicated that the range of the XB-35 would most likely be 1600 miles shorter than anticipated. In addition, the maximum speed was estimated to be 24 mph slower than anticipated. Consequently, General Arnold began to question the wisdom of any extensive B-35 production program. In the meantime, the Martin company was experiencing severe shortages of trained engineers (many had been drafted) who could work on the B-35 project and had encountered delays in setting up the necessary tooling. These problems had forced Martin to push back the delivery date of the first B-35 to 1947. As a result, the USAAF concluded that it was unlikely that the B-35 would be ready in time to contribute to the war effort, and cancelled the Martin B-35 production contract on May 24, 1944.

However, this did not spell the death of the B-35 project, since the Air Technical Service Command felt that the XB-35 flying wing project was worthwhile for test purposes even if it never achieved operational status. In December of 1944, the USAAF decided that Northrop should go ahead and build the XB-35 and YB-35 aircraft as test vehicles. The first six of the YB-35s would be built on the XB-35 pattern, but with certain individual differences. On June 1, 1945, orders were issued to have two of the YB-35 airframes fitted with Allison J35-A-5 jet engines. The jet-powered flying wing was initially assigned the designation YB-35B, but this was later changed to YB-49. In 1945, after two more YB-35s had been added to the first YB-35 lot to replace the two that were earmarked for jet conversion, the USAAF told Northrop to manufacture the remaining 5 airplanes on the YB-35 contract to more advanced specifications, which resulted a redesignation to YB-35A.

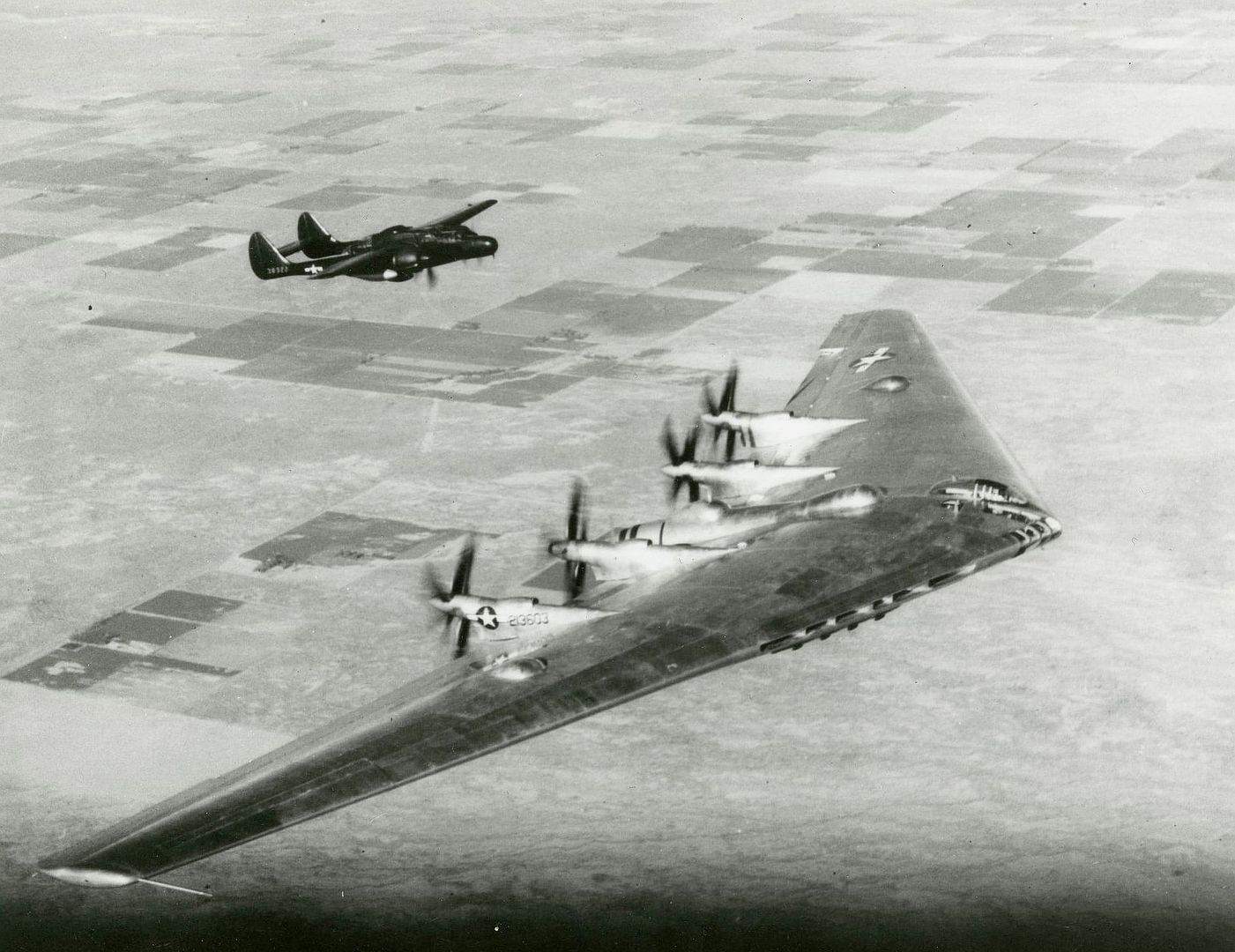

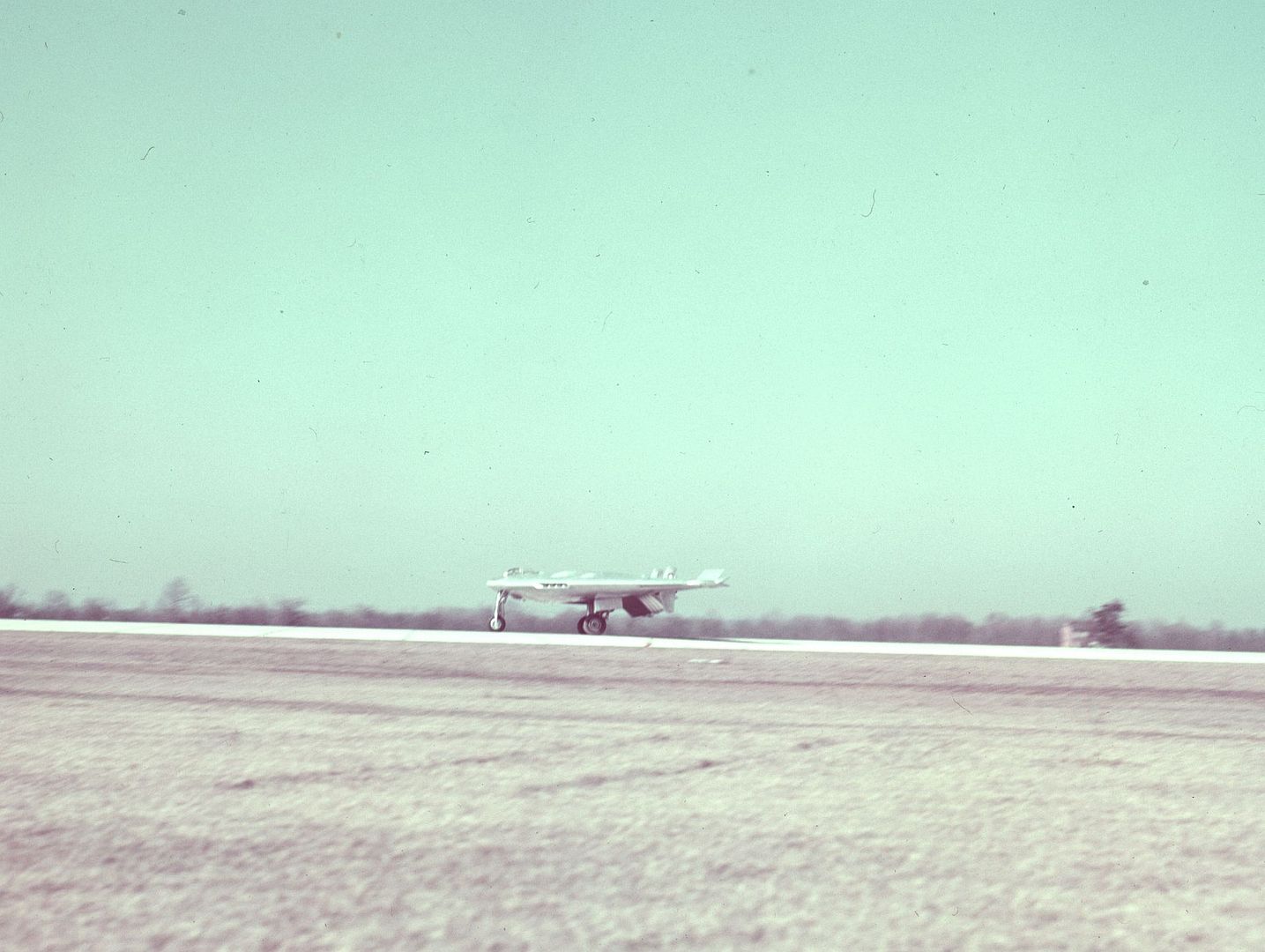

The first XB-35 (serial number 42-13603) took off on its maiden flight on June 25, 1946, with Max Stanley as pilot and Dale Schroeder as flight engineer. On this first flight, the aircraft was flown from Hawthorne to Muroc Dry Lake, a flight lasting 45 minutes. Almost immediately, the flight test program ran into difficulties. Gear box malfunctions and propeller control difficulties caused the XB-35 to be grounded on September 11 after only 19 flights.

The second XB-35 (serial number 42-38323) took to the air for the first time on June 26, 1947. Only eight flights took place before Northrop was forced to ground this plane too.

The dual counter-rotating propellers and their gearboxes proved to be totally unsatisfactory, and both XB-35s had to be grounded in September of 1947 so that their dual-rotating propellers could be replaced by single-rotation propellers. Following the fitting of the new single-rotation propellers and the mounting of simpler gearboxes, flight testing of the first XB-35 was resumed in February of 1948. Seven more flights were made by the first XB-35 from February 12 to April 1, 1948. The new propeller installations operated without any particular mechanical difficulties, but there was considerable vibration and the performance of the aircraft was reduced.

The XB-35's intricate exhaust system was a maintenance nightmare, and by the middle of 1948 the cooling fans of the R-4360 engines were beginning to show signs of metal fatigue.

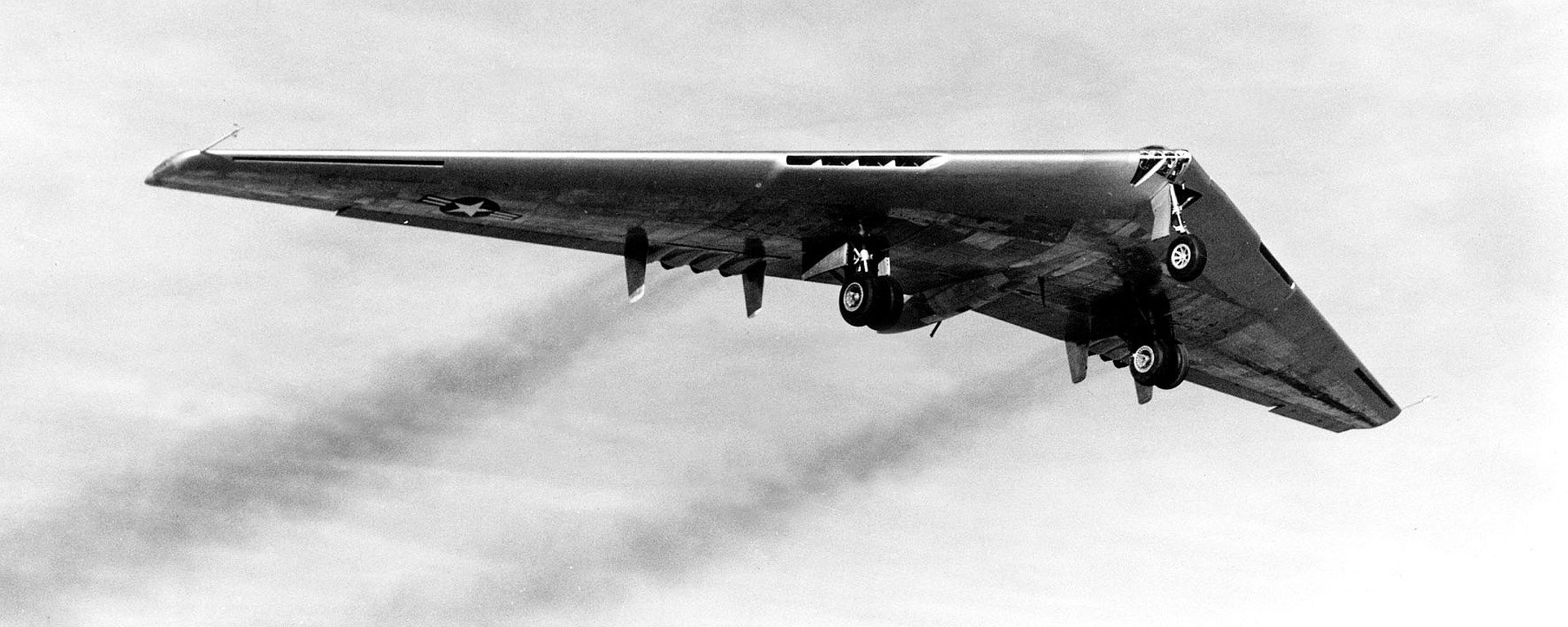

The first YB-35 (42-102366) flew on May 15, 1948, which was the only example actually fitted with defensive armament. The two XB-35s had carried only dummy turrets. The YB-35 was fitted with single-rotation propellers. This was destined to be the only one of the 13 YB-35s ordered that actually flew. Of the original 13 YB-35s ordered, four had been scheduled to be used as sources of spare parts for the extensive flight test program that was planned. However, by mid-1948 the piston-engined B-35 was definitely outdated, and the program was clearly doomed. A propeller-driven aircraft was simply much too slow for the era of jet propulsion, and the flying wing as it then existed was much too unstable to make a good bombing or camera platform. Nevertheless, the Air Force did not want to throw in the towel completely after having spent so much money, and for a while considered studying the feasibility of adapting the B-35 for the air-refuelling role, but this was not pursued any further.

By the end of 1948, it was planned for five YB-35s and 4 YB-35As to be converted to six-jet configuration and fitted with cameras and redesignated RB-35B (later to be redesignated YRB-49A). One YB-35 was earmarked for static testing, and another jet-converted YB-35A was to be fitted out as a test-bed for the Turbodyne T-37 turboprop engine, which was then under development. This test aircraft was to have been designated EB-35B (it was the last of the 13 prototypes) and would be capable of carrying two T-37 engines, although only one of these engines would actually be fitted initially. The second XB-35 was to have been fitted with a flexible-mount gear box to try and cure the problems with the vibrations in the single-rotation propellers.

In August of 1949, the two XB-35s and the first two YB-35s were scrapped. In November, the Air Staff cancelled plans for further conversions of YB-35s and YB-35As to jet propulsion. Scrapping of the remaining YB-35 airframes started in December of 1949 and was completed by March of 1950. The disassembly of the EB-35B testbed began in March of 1950. None of the series production B-35A were ever built.

Serials of Northrop B-35

42-13603 Northrop XB-35

42-38323 Northrop XB-35

42-102366/102378 Northrop YB-35

102367 and 102368 converted to YB-49.

102368 w/o 6-5-48

102369/102375 scrapped before flying

102376 converted to YRB-49A

102377,102378 scrapped before flying

Specification of Northrop XB-35

Engines: Two Pratt & Whitney R-4360-17, and two R-4360-21 Wasp Major air-cooled radials rated at 3000 hp each. Performance: Maximum speed 391 mph at 35,000 feet, cruising speed 183 mph. Service ceiling 39,700 feet. An altitude of 35,600 feet could be attained in 57 minutes. Range was 8150 miles at 183 mph with a 16,000 pound bombload, or 720 miles at 240 mph with 51,070 pounds of bombs. Dimensions: wingspan 172 feet 0 inches, length 53 feet 1 inches, height 20 feet 1 inches, wing area 4000 square feet. Weights: 89,560 pounds empty, 180,000 pounds gross, 209,000 pounds maximum. Armament: (only fitted to the first YB-35) Four 0.50-inch machine guns in remotely-controlled dorsal turret. Four 0.50-inch machine guns in remotely-controlled ventral turret. Four 0.50-inch machine guns in the rear of the tail cone. Two 0.50-inch machine guns in each of four barbettes installed above and below the wing outboard of the outermost engines. The guns were remotely sighted by gunners sitting in stations in a bubble in the upper rear part of the tailcone, in a ventral station, and in a position in the pilot's bubble immediately behind the pilot's seat. The bombs were carried in eight individual bomb bays cut into the under surface of the wing outboard of the main crew cabin.

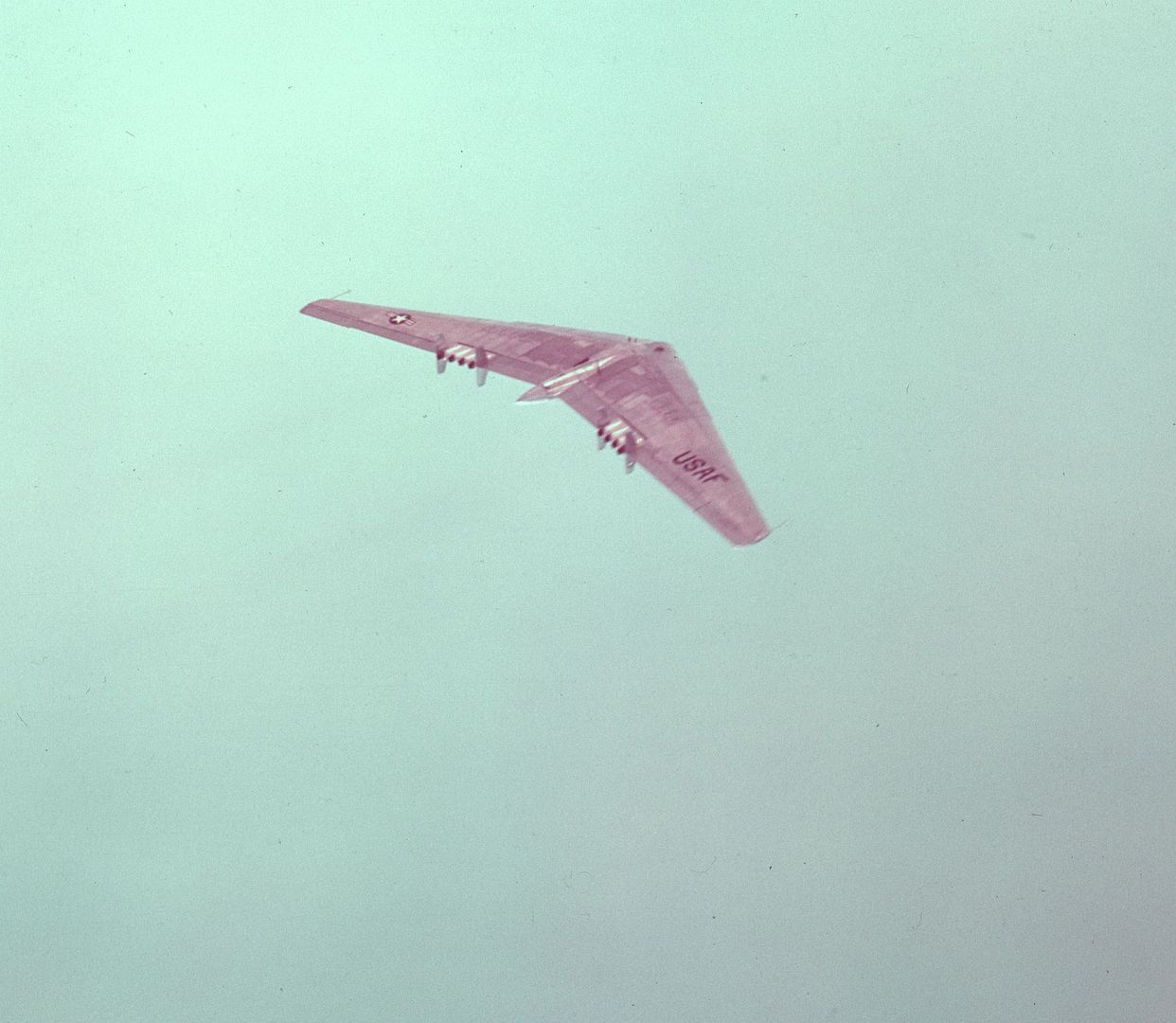

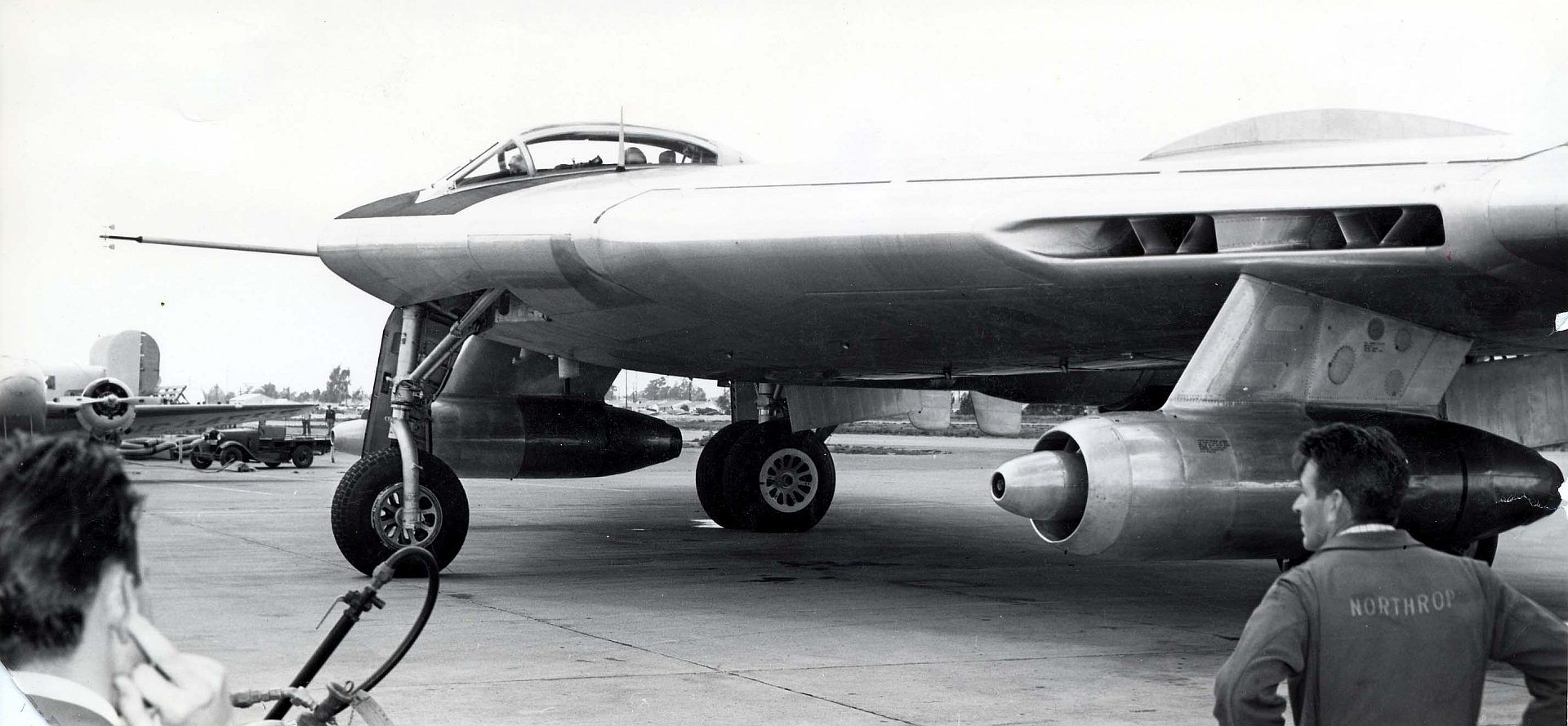

YB-49

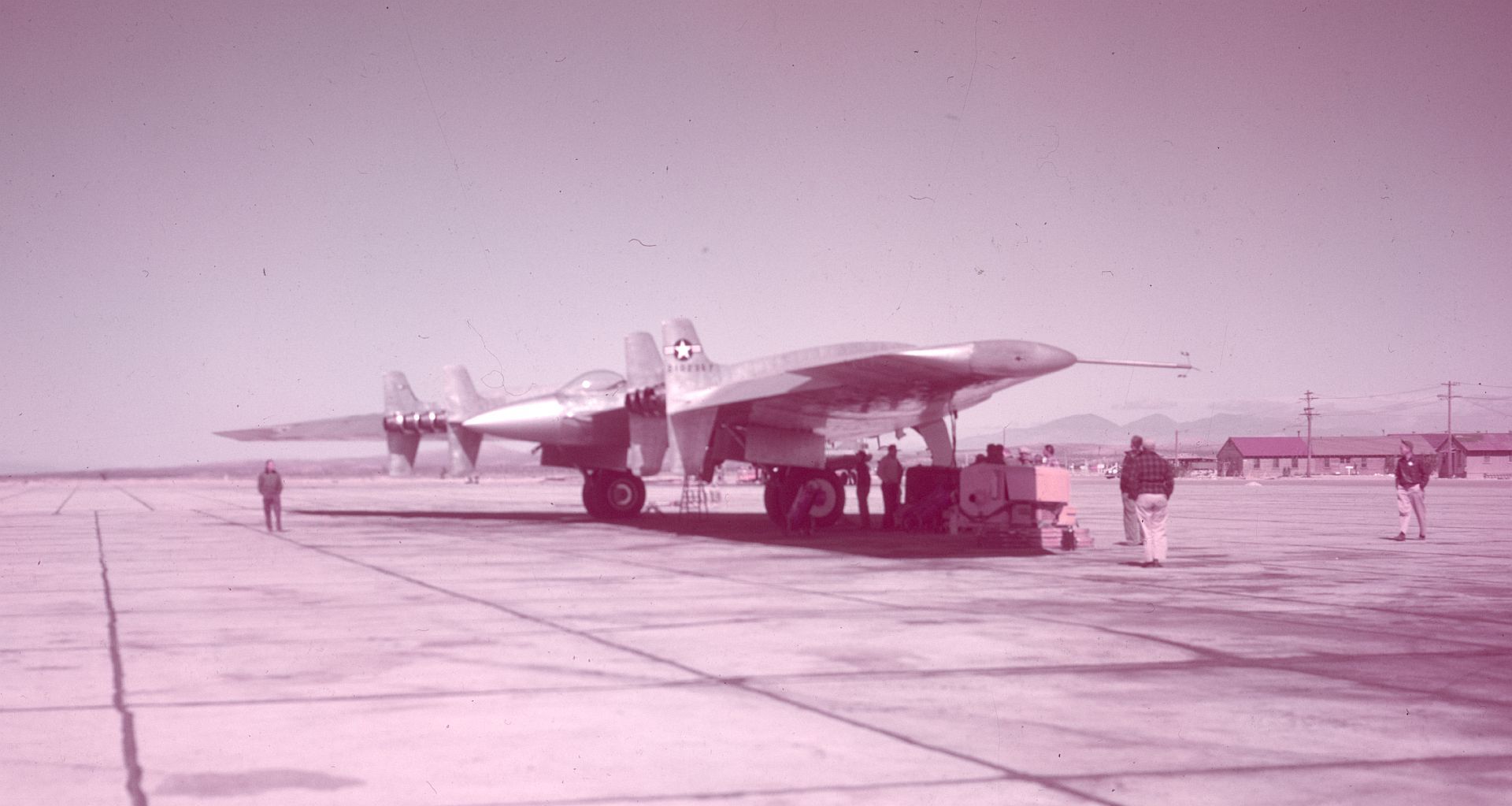

On June 1, 1945, a contract ordering the conversion of two of the YB-35 flying wings into jet configuration was issued. The four Wasp Major engines of the B-35 were to be replaced by eight 4000 lb.s.t. Allison J35-A-5 turbojets buried inside the wing, four on each side. The engines were to be fed by intakes cut into the leading edges of the wing. The designation given to the jet-powered flying wing bomber was originally supposed to have been YB-35B, but this was changed to YB-49 before the first flight took place.

Since the addition of jet power promised a marked improvement in the performance of the flying wing, work on the YB-35 project was abandoned and plans were made to convert all the YB-35 airframes beyond the first to YB-49 configuration. The airframes for the second and third YB-35 (42-102367 and 42-102368) were selected for modification to YB-49 configuration. The eight 4000 lb.s.t. Allison J35-A-5 turbojets were mounted in banks of four on either side of the wing. The leading edge was reconfigured to provide a low drag intake slot for each of the two sets of jet engines. In order to achieve greater stability a pair of four small vertical fins were added to the wing trailing edge extending both above and below the wing just inboard and outboard of the engines. In addition , a set of wing fences were added to the upper wing surfaces extending all the way from the vertical fins to the wing leading edge. These surfaces were added in order to provide a stabilizing effect that the propellers and propeller shaft housings had given to the YB-35. All guns except the tail cone guns were eliminated. The crew of seven were housed entirely within the wing center section, with the pilot seated underneath a large bubble canopy near the wing leading edge. For long flights, an additional off-duty crew of six members could be carried in quarters in the tail cone just aft of the flight section.

Conversion of the YB-35 to the YB-49 configuration was originally scheduled to be completed by June of 1946. However, this schedule slipped by more than a year because of unforseen problems encountered in adding fins to the wings.

The first YB-49 (42-102367) took off on its maiden flight on October 21, 1947 from the Northrop field at Hawthorne California, piloted by Northrop's chief test pilot, Max Stanley. At the end of the flight, it landed at Muroc Air Force Base where it was to carry out its test program. It was later joined by the second YB-49 (42-102368), which flew for the first time on January 13, 1948.

Over twenty months of flight testing was carried out. Northrop test pilots flew the first YB-49 for almost 200 hours, accumulated in some 120 flights. Air Force pilots completed about 70 hours of flight time in the first YB-49, totaled in some 20 flights. The second YB-49 carried out some 24 flights with Northrop crews for a total of about 50 hours. The Air Force crews flew the second YB-49 five times for about 13 hours. A maximum speed of 520 mph was achieved, and a service ceiling of 42,000 feet was attained. A normal 10,000 pound bombload could be carried for an estimated 4000 miles on 6700 gallons of fuel, less than half the range of the piston-engined B-35. In spite of the added rudders and wing fences, the YB-49 design still encountered some stability problems which were never fully corrected.

On April 26, 1948, the first YB-49 achieved a milestone of sorts, the aircraft staying up in the air for 9 hours, 6 hours of which were above 40,000 feet. This is believed to have set an unofficial record for that period.

On May 28, 1948, the second YB-49 (42-102368) was turned over to the USAF. Only a few days later, tragedy struck. On the morning of June 5, 1948, 42-102368 crashed just north of Muroc Dry Lake. The pilot, Air Force Capt. Glenn Edwards, and all four other members of the crew were killed. What caused the crash is not known, but it was suspected that Capt Edwards managed to surpass the "red line" speed of the aircraft while descending from 40,000 feet, causing the outer wing panels to be shed and the aircraft to disintegrate in midair. Muroc AFB was renamed Edwards AFB on December 5, 1949 in honor of the late Capt. Glenn Edwards.

In spite of the crash, the Air Force still had sufficient confidence in the YB-49 that they continued with plans for the conversion of nine of the remaining eleven YB-35 airframes to a basically similar RB-35B strategic reconnaissance configuration with 8 jet engines, with another airframe to be used as a static test vehicle. In addition, orders were placed for 30 new RB-49s to be built from scratch.

Many deficiencies turned up in the second series of tests. The J35 turbojets of the YB-49 were extremely thirsty for fuel, and the jet-powered YB-49 had only half the range of the YB-35 that preceded it. The test pilots complained that the aircraft was extremely unstable and difficult to fly. They also maintained that the YB-49 was completely unsuitable as a bombing platform-- it could not hold a steady course or a constant airspeed and altitude, and that here was a persistent rocking motion in yaw, which tended to upset the bomb sights. In comparison with the B-29, the YB-49 had a much poorer circular average error and range error during bombing trials. In retrospect, many of the stability problems with the flying wing may have been insoluble with the technology available in the late 1940s, requiring the fly-by-wire technology that was developed much later for their solution.

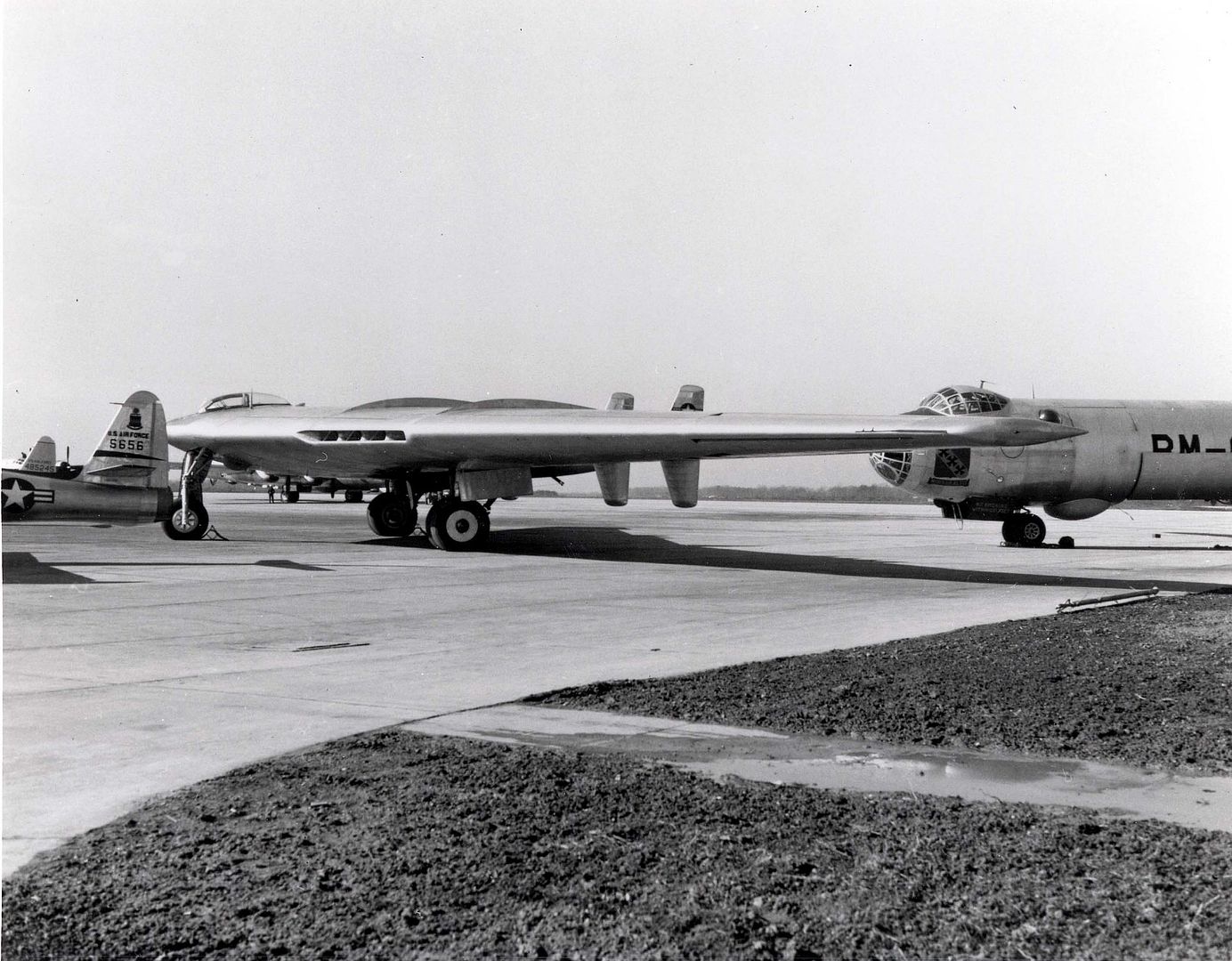

By 1948, progress in range extension by other projects had reached the level that the YB-49 was now considered as being a medium bomber rather than a heavy bomber. This put it in competition with the XB-46, XB-47, and XB-48 projects, where the XB-35 had been considered as a B-36 competitor.

On January 4, 1949, the Air Force ordered Northrop to fly 42-102367 from Muroc AFB to Washington DC for a military air display at Andrews AFB. It departed Muroc on February 9, 1949, and when it landed at Andrews it had set a new transcontinental speed record of 4 hours and 20 minutes for the 2258-mile flight, averaging 511.2 mph. The pilot was Major Robert Cardenas, who had replaced the late Capt Glen Edwards as chief of flight test on the Northrop flying wing test program. Northrop test pilot Max Stanley was also on board. During the display at Andrews AFB, President Harry Truman inspected the YB-49 and was impressed.

On the way back to California, 42-102367 stopped off at Wright Field in Dayton so that the Air Force could take a look at the new plane. On February 23, the YB-49 took off to return to Muroc, but during the flight three of the J35 engines on the left and one on the right side caught fire, forcing an emergency landing at Winslow, Arizona. There were hints of sabotage, since it was later determined that the cause of the engine fires was that the turbine oil reserves had not been filled in any of the J35 engines during refuelling at Wright Field. The FBI was called in to investigate, but a blanket of security was thrown over the entire affair and the incident was all but forgotten.

By October of 1948, the YB-49 was clearly a doomed program. Nevertheless, testing continued, and there was always a remote possibility that its problems might be cured. However, the accidents and stability problems continued. On April 26, 1949, a fire occurred in one of the aircraft's engine bays, forcing $19,000 worth of repairs. The handwriting was now on the wall-- the contract for 30 new RB-49A aircraft was canceled in April of 1949. In November of 1949, the conversion of existing YB-35 airframes to YB-35B configuration was also cancelled.

On March 15, 1950, the cancellation of the entire YB-49 program became official. On that very same day, the first YB-49 (42-102367) got itself involved in a ground taxiing accident at Edwards AFB. There were no fatalities, but crewmen were injured and the aircraft was totally destroyed by fire. Excessive shimmy of the nosewheel followed by total gear collapse were blamed for the mishap.

The movie *War of the Worlds* filmed between 1952 and 1953 used stock footage of one of the YB-49s. In the movie, it was the plane which delivered a nuclear bomb onto the attacking Martian force. Many people confuse this plane with the B-2 stealth bomber, which was designed much later.

Specification of Northrop YB-49

Engines: Eight 3750 lb.s.t. Allison J35-A-15 turbojets. Performance: Maximum speed 493 mph at 20,800 feet, 464 mph at 35,000 feet. Cruising speed 429 mph. Stalling speed 90 mph. Service ceiling 45,700 feet, combat ceiling 40,700 feet. Initial climb rate 3785 feet per minute. Combat radius 1615 miles with 10,000 pound bomb load. Ferry range 3575 miles. A normal 10,000 pound bombload could be carried for 4000 miles on 6700 gallons of fuel. A load of 36,760 pounds of bombs could be carried 1150 miles. Dimensions: Wingspan 172 feet, length 53 feet 1 inches, height 15 feet 2 inches, wing area 4000 square feet. Weights: 88,442 pounds empty, 133,559 pounds combat, 193,938 pounds gross.

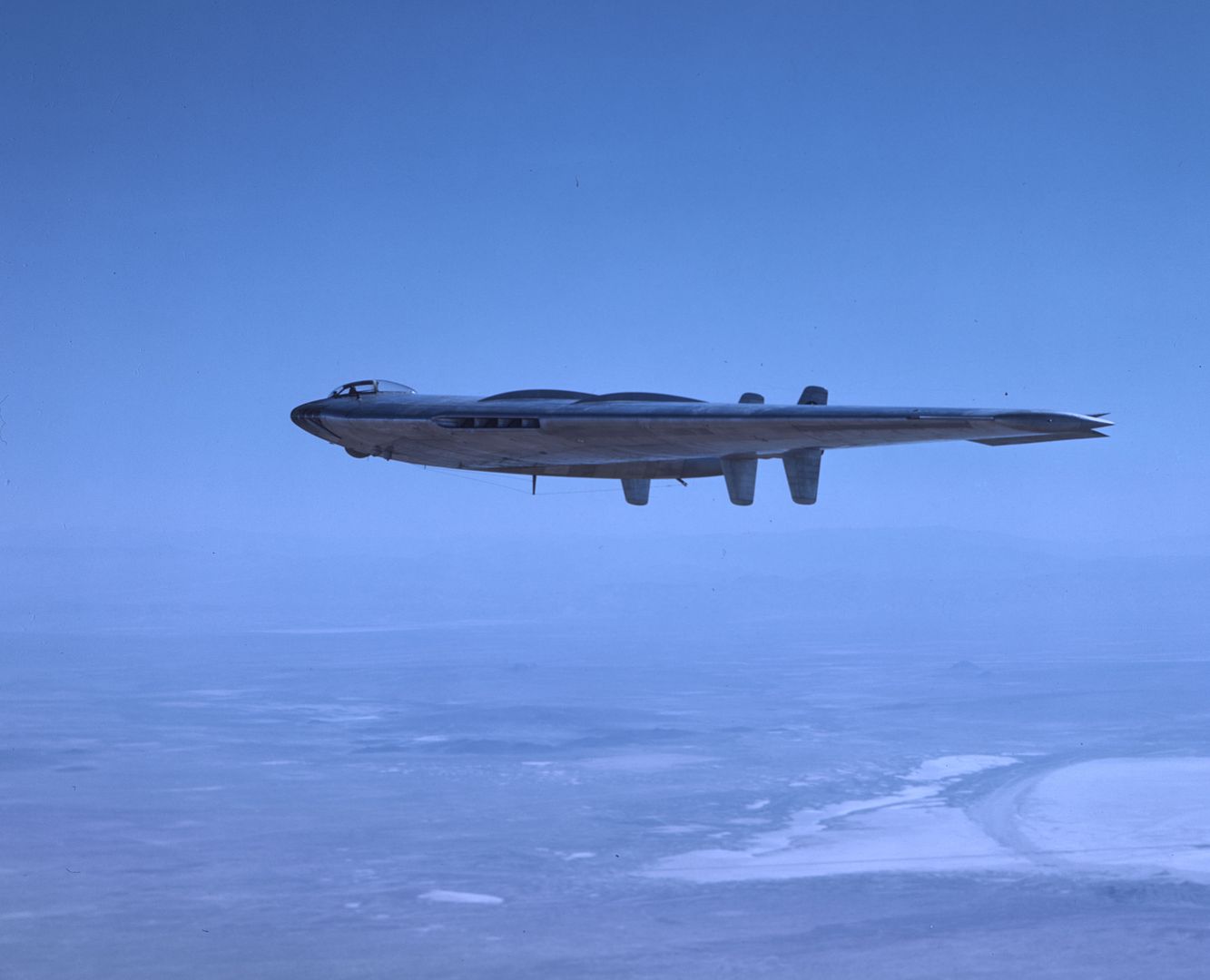

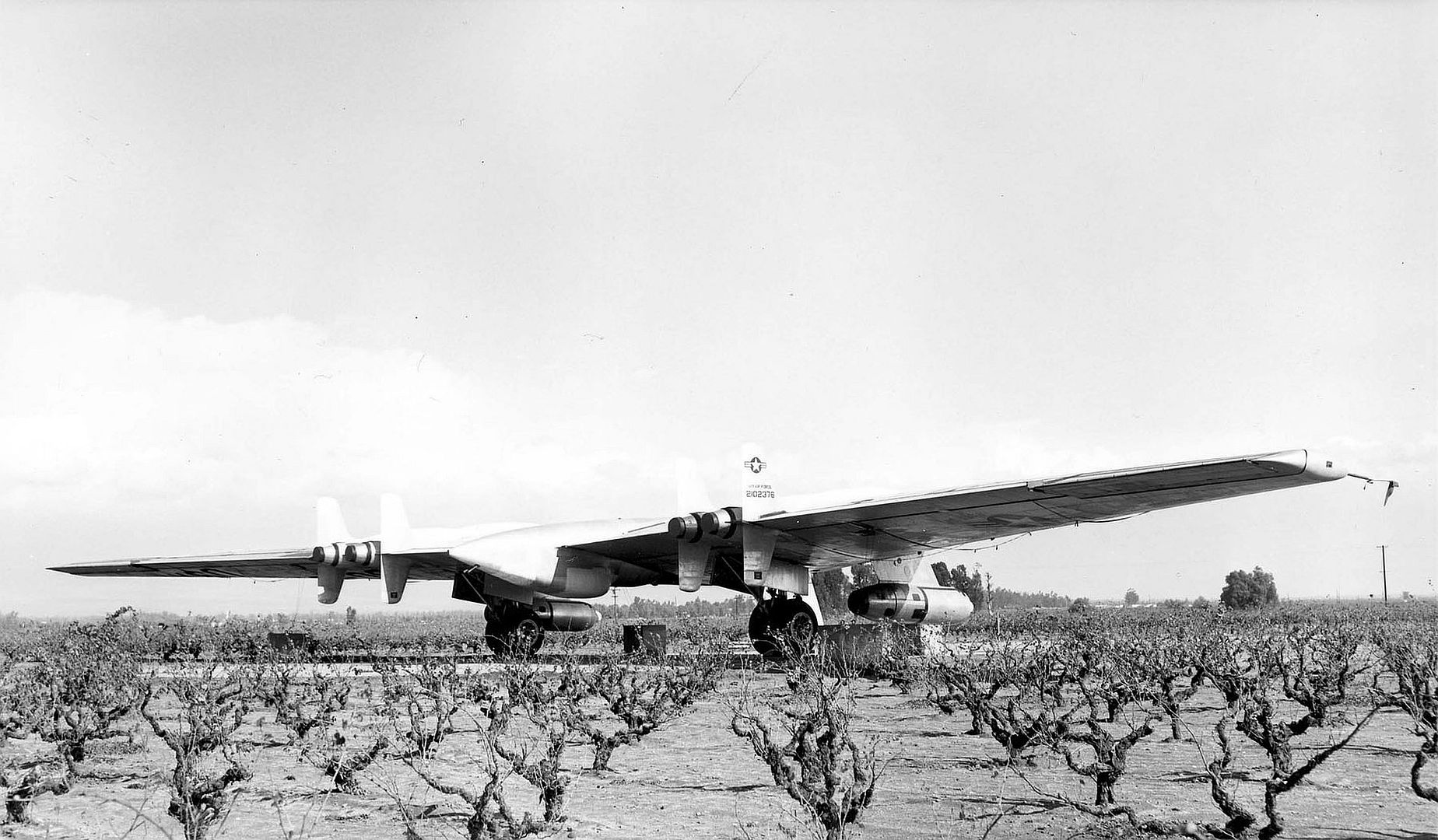

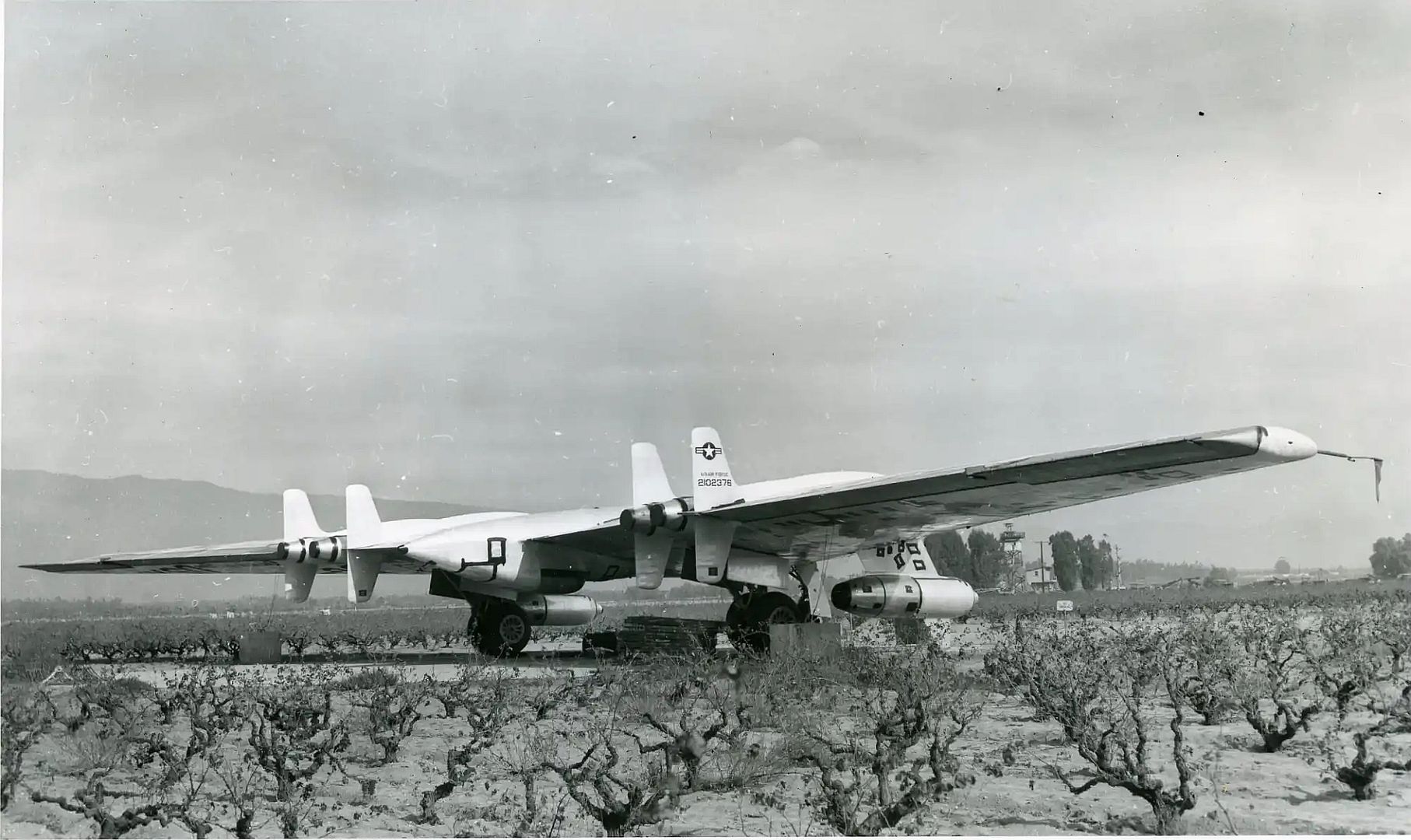

YRB-49A

Following the cancellation of the B-49 project, the Air Force still decided to fund the conversion of the tenth YB-35 (42-102376) as a testbed for an unarmed, long-range photographic reconnaissance aircraft. The designation YRB-49A was assigned to the conversion, with the company designation being Model NS-41. It was powered by four 5000 lb.s.t. Allison J35-A-19 engines mounted in the wings, two on each side, plus two more J35s suspended in pods below the wing leading edge. The placement of two engines in nacelles allowed more room for fuel in the wings, the additional fuel being necessary for the long-range reconnaissance mission. In addition, the engine pylons acted as vertical stabilizers which would supposedly help to correct the yaw-axis stability problems that had been encounted during YB-49A testing.

The crew was six--pilot, copilot, flight engineer, photo navigator, radar navigator, and photo technician. Photographic equipment was installed in the tail cone bay just below the center section.

Northrop received a letter contract on June 12, 1948 for preliminary engineering work leading perhaps to an eventual production contract for 30 aircraft. Serials were 49-200/229. This contract was signed on August 12, 1948. The Air Force believed that the nation would benefit from the pooling of Northrop's engineering skill and Convair's experience in quantity production of large aircraft, and the contract stipulated that only one of the aircraft was to be built by Northrop, with the remaining 29 to be built by Convair at its government-leased plant in Fort Worth, Texas.

However, it soon became apparent that the proposed six-jet RB-49A would be much slower than the B-47, and the Air Force Board recommended immediate termination of the RB-49A. This was done formally in late December of 1948. The funds that had been allocated to the RB-49A were then re-allocated to more B-36s. The cancellation became official in mid-January of 1949, and Northrop was directed to stop all work on the project except for completion and test of a single YRB-49A as part of a proof-of concept research and development program.

The YRB-49A took off on its first test flight on May 4, 1950. Its first flight was from Hawthorne to Edwards AFB. Tests were conducted at Edwards AFB for a period of time. On August 10, 1950, during its tenth test flight, the cockpit canopy blew off, tearing away the pilot's oxygen mask and injuring him slightly. Fortunately, the flight engineer was able to supply enough emergency oxygen to the pilot so that he was able to land the aircraft safely.

A short period of only 13 test flights took place until the aircraft was placed in storage in late 1950. In early 1952, the YRB-49A was flown to Northrop's Ontario International Airport facility (in California) for the installation of a device that would improve the stability. However, at this time the Air Force had cut off further funding for the YRB-49A project, and the aircraft remained sitting out in the open in dead storage for a period of time. It was finally scrapped by the Air Force in November of 1953.

(Text by J Baugher)

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources