Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Convair R3Y Tradewind

Convair R3Y Tradewind

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

Main AdminDuring World War II the United States Navy relied on a large number of patrol/bomber flying boats (PBY/PBM models). As the war wound down the Navy saw a continued need for flying boats and desired an aircraft larger than the PBY Catalina and PB2Y Coronado aircraft which were heavily used during the war.

Main AdminDuring World War II the United States Navy relied on a large number of patrol/bomber flying boats (PBY/PBM models). As the war wound down the Navy saw a continued need for flying boats and desired an aircraft larger than the PBY Catalina and PB2Y Coronado aircraft which were heavily used during the war.

In 1945 the United States Navy issued a formal request for a large flying boat. They wanted manufacturers to take advantage of new technology developed during WWII…specifically laminar flow airfoils and the still evolving turboprop/turbojet technology. The P-51 was the first aircraft developed intentionally with laminar flow airfoils. However research showed the Mustang airfoils were not manufactured with sufficient surface quality to produce true laminar flow on the wing.

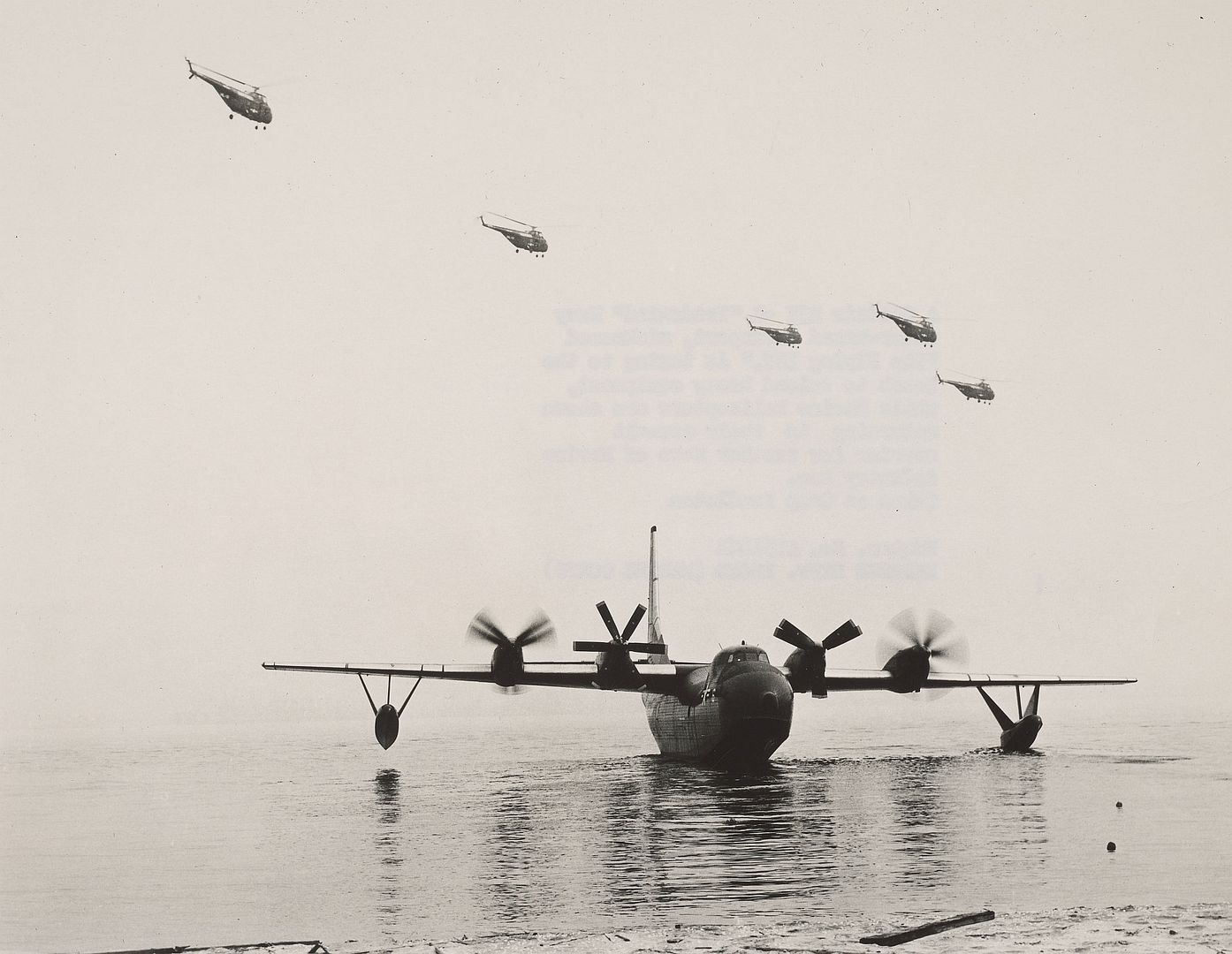

The new aircraft’s primary mission would be over-water patrol from temporary forward bases. Secondary roles would include air-sea rescue, anti-sub patrol, and bombing of merchant shipping. The Navy intended to combine very new technology, the turbine (jet) engine, with very old technology, the seaplane.

Seaplane hull development had been underway at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the Stevens Institute of Technology (SIT) for many years. Convair was also doing in-house testing under direction of Ernest G. Stout, the "seaplane admiral" since 1943. Stout had been using model aircraft similar to full-scale aircraft for development since 1938 and added radio/remote control aircraft about five years later.

Between the NACA/SIT work and Convair’s in-house development a revolutionary new hull design was developed which had improved hydrodynamic stability such as reduced skipping and porpoising, minimized spray and improved rough-water performance...in other words, a more seaworthy flying boat.

Three companies submitted proposals in response to the Navy’s request, Convair, Martin and Hughes. Hughes design, the H-4, better known as the “Spruce Goose,“ was the largest, slowest and most expensive (which was subsequently eliminated first). The Convair and Martin designs were essentially equal, but Convair won due to better performance and logistic superiority (requiring less fuel for a given mission).

The first American jet fighter was the Bell P-59 Airacomet which first flew 1 October 1942. However, during production it was determined the P-59 under-performed the North American P-51 Mustang in both top speed and range. This lead to the P-59 never reaching combat.

Rather than face a similar fate of the Bell P-59 Airacomet, Convair proposed powering the new aircraft with a turboprop. A turboprop is a turbine (jet) driving a propeller shaft. This would allow them to provide better fuel economy leading to a longer range than a pure jet. Convair would go on to be the first company in US to fly a turboprop aircraft with their XP-81, a single seat, long range escort fighter that combined use of both turbojet and turboprop engines on 21 December 1945.

The Navy issued a Procurement Directive in May of 1946 and issued the XP5Y-1 designation to the project. The contract that followed called for one bare aircraft in 26 months with a second complete aircraft ten months later. This was the 2nd time the P5Y-1 designation was assigned by the Navy. The first aircraft given the P5Y-1 designation was a proposed twin-engined version of the Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberator in 1942. This aircraft was dropped in favor of the Lockheed P2V Neptune.

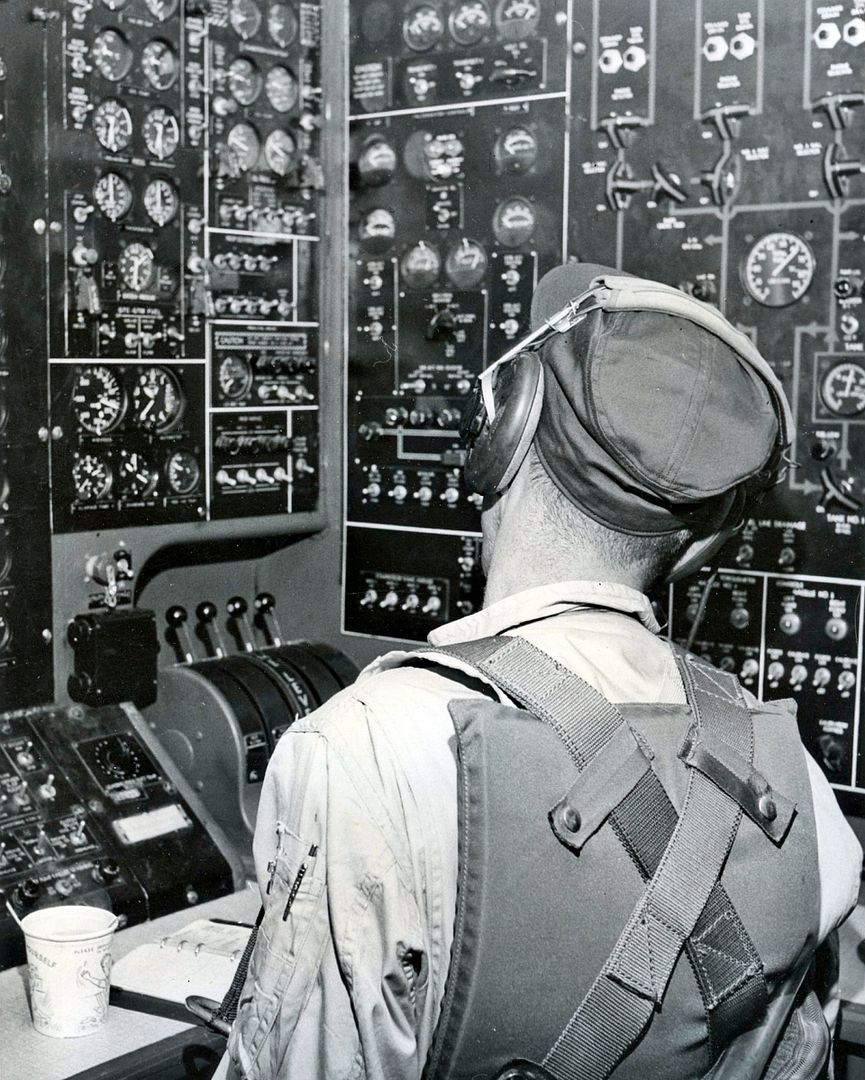

Initially the XP5Y-1 was designed as a large, long-range recon flying boat powered by four Westinghouse 25D (T30) engines. The T30 was selected simply because it was expected to be first suitable, available engine that could drive the Hamilton Standard Super-Hydromatic props which would be 15-ft 1-in in diameter.

In April 1946 Westinghouse workers walked out due to an industrial dispute. This delayed the T30 availability estimate until 1949 well after the July 1948 deadline for the first prototype. Alternatives were sought from Allison and Pratt & Whitney. Convair selected the experimental Allison XT40 paired with six-bladed contra-rotating propellers simply because the T40 would be available first. The T40 was two gas-powered turbines (the Allison T38) mounted side-by-side and coupled via a set of reduction gears to drive a single prop shaft. The Douglas A2D and North American A2J were developed with the Allison T40-A-6. The Tradewind was using the T40-A-10 which was essentially the same with minor accessory relocation.

Convair had initially considered a four prop aircraft using T-40s inboard and T-38s outboard, but settled on quad T-40s to provide logistic commonality. The T-40 was rated at 5,100 shaft horsepower and was designed so that either T-38 could independently drive the six-blade propeller assembly. Once airborne, one T-38 unit could be shut down for maximum fuel economy.

The Tradewind is the only T-40 powered aircraft to reach production. The decision to employ the T-40 would ultimately be the downfall of the R3Y. The first sign of trouble occurred when every non-flight test encountered numerous problems with the initial Allison XT40-A-4 engines.

Convair’s extensive model testing program completed 2000 test runs between 1947 and 1950. Twenty-seven models were tested during this time to arrive at the final XP5Y-1 design. The second prototype was redesigned to be an Anti-Submarine Warfare aircraft with aerial mine-laying (16,000 carried in the nacelles) capability. The first two prototypes built were armed with 8,000 pounds of munitions (bombs, mines, depth charges, torpedoes) and five pairs of 20-mm cannon with forward and aft side turrets and a tail turret.

First Flight and Retasking

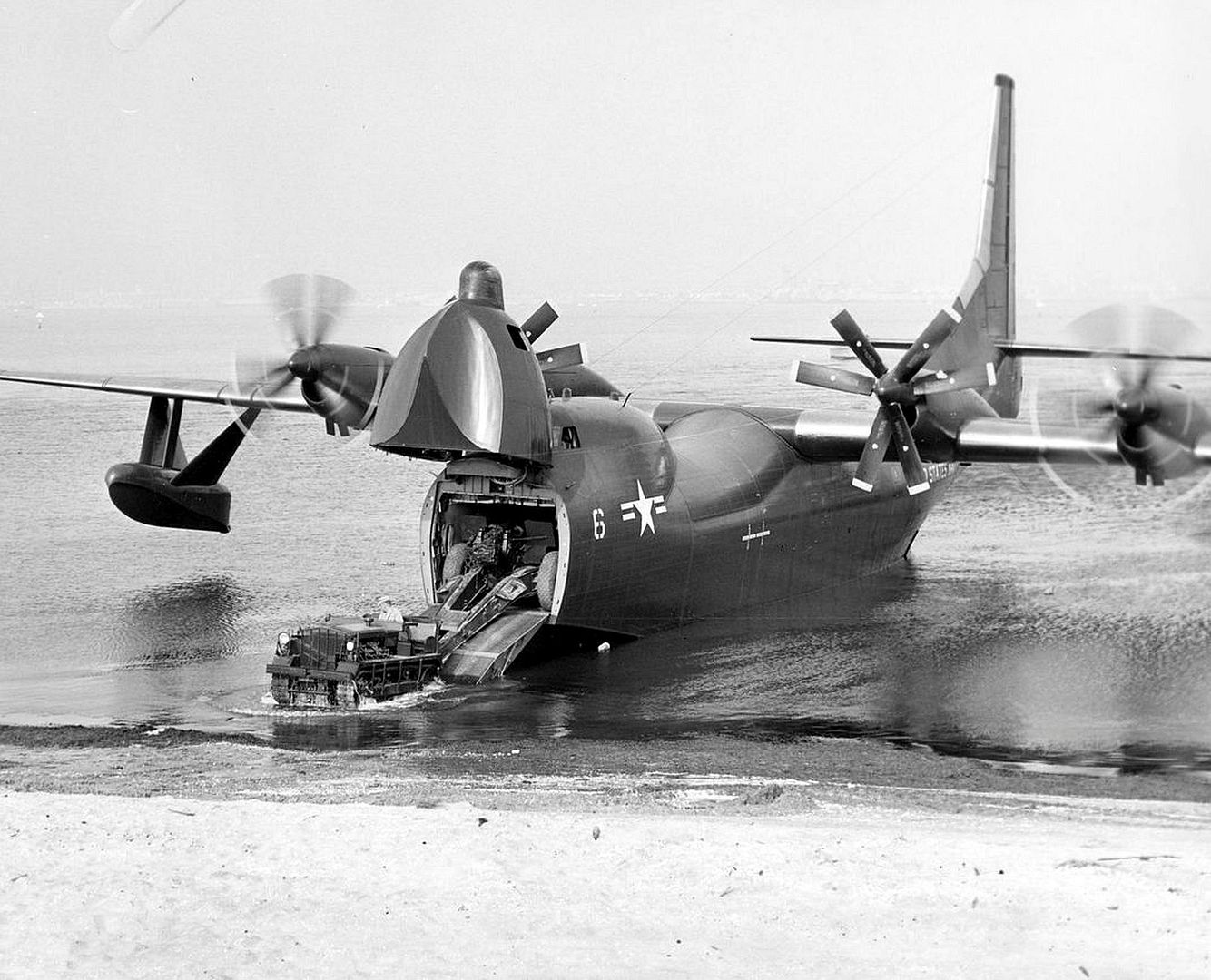

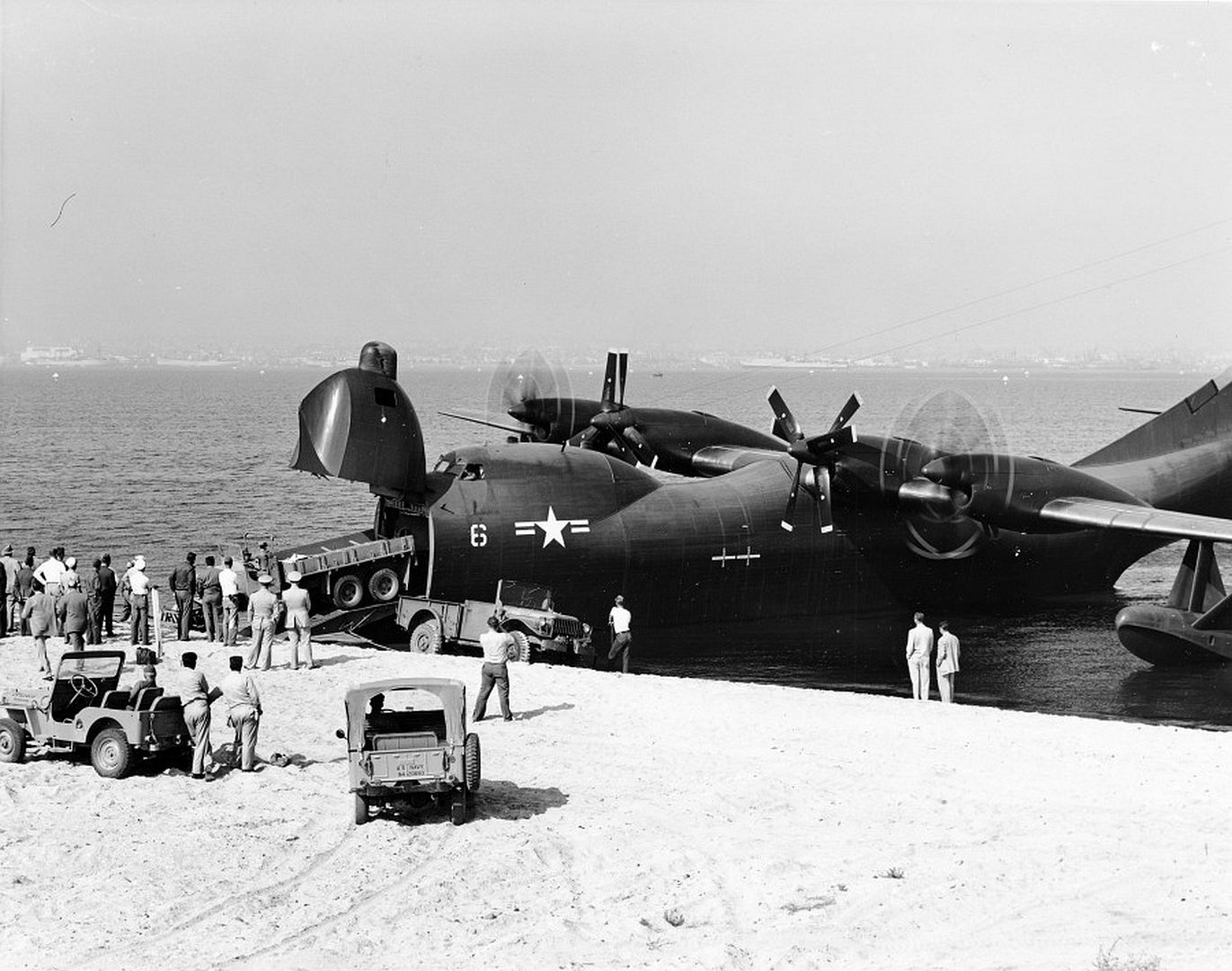

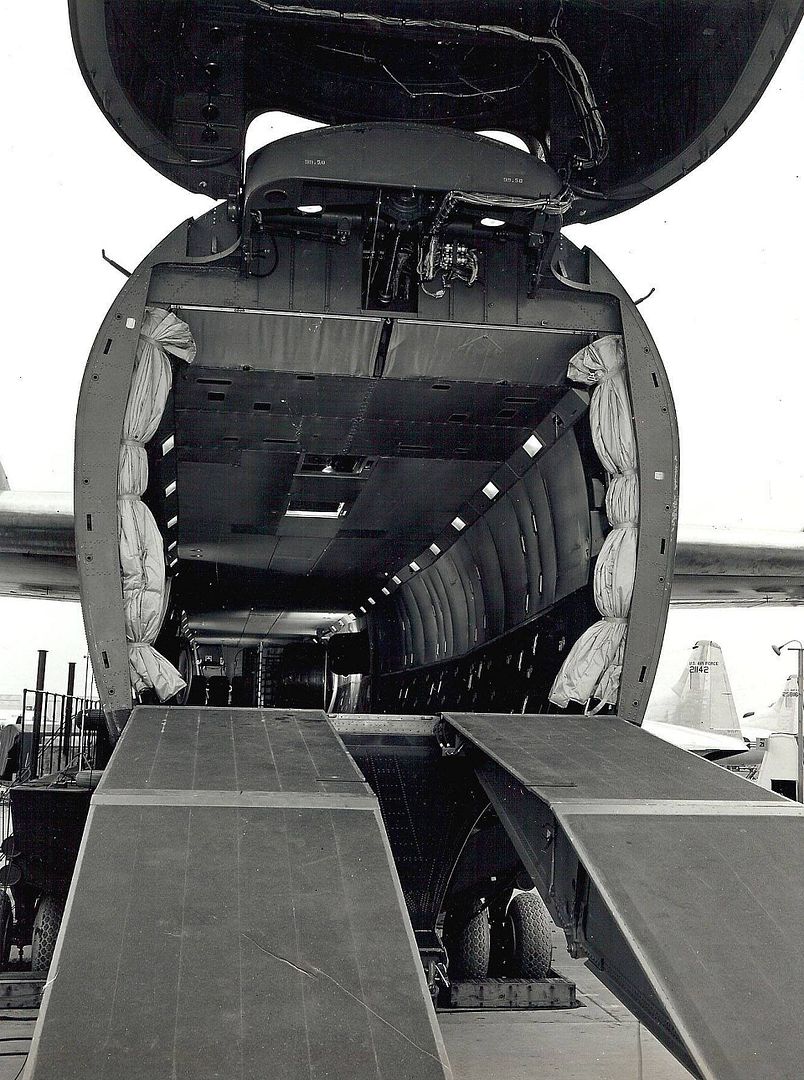

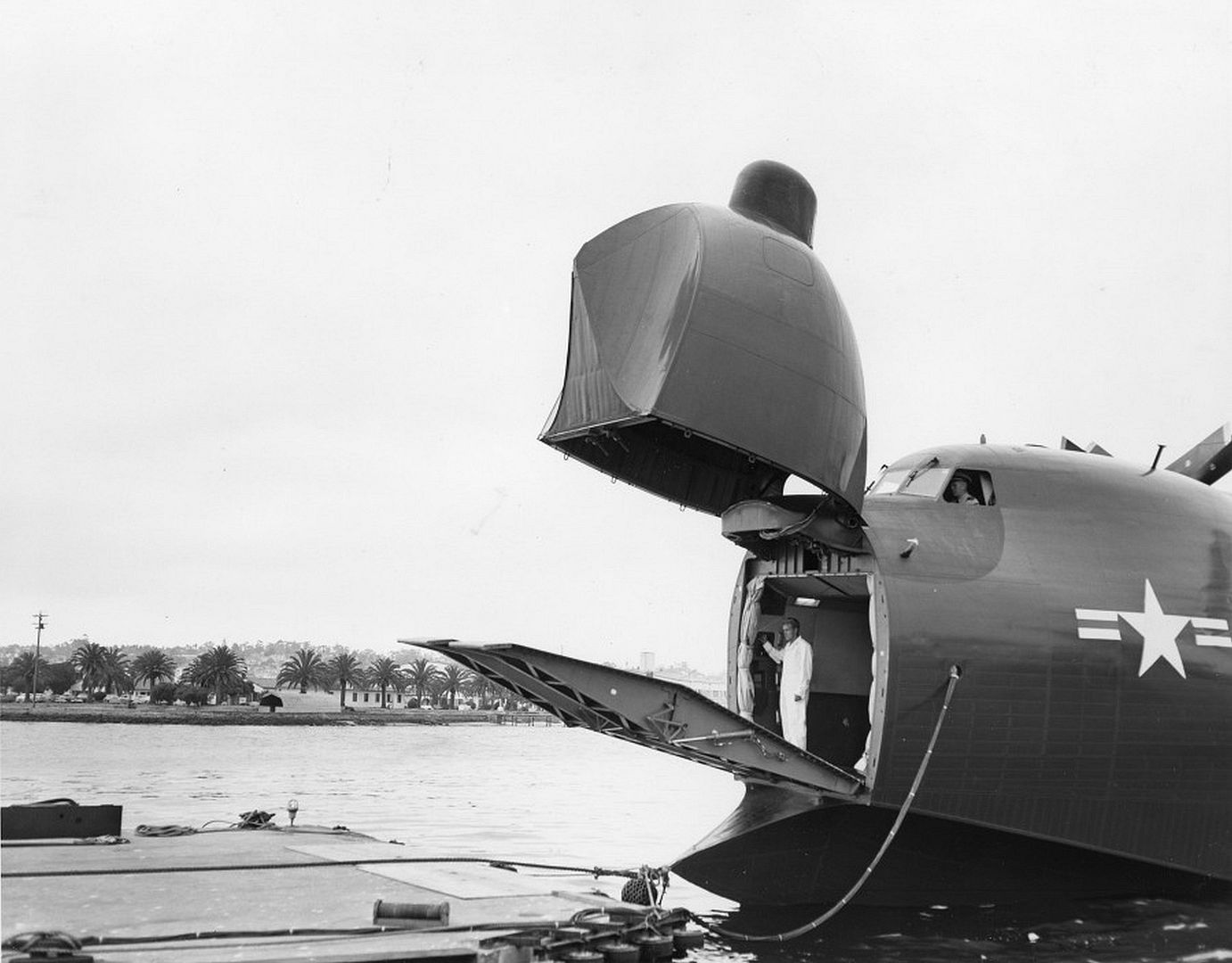

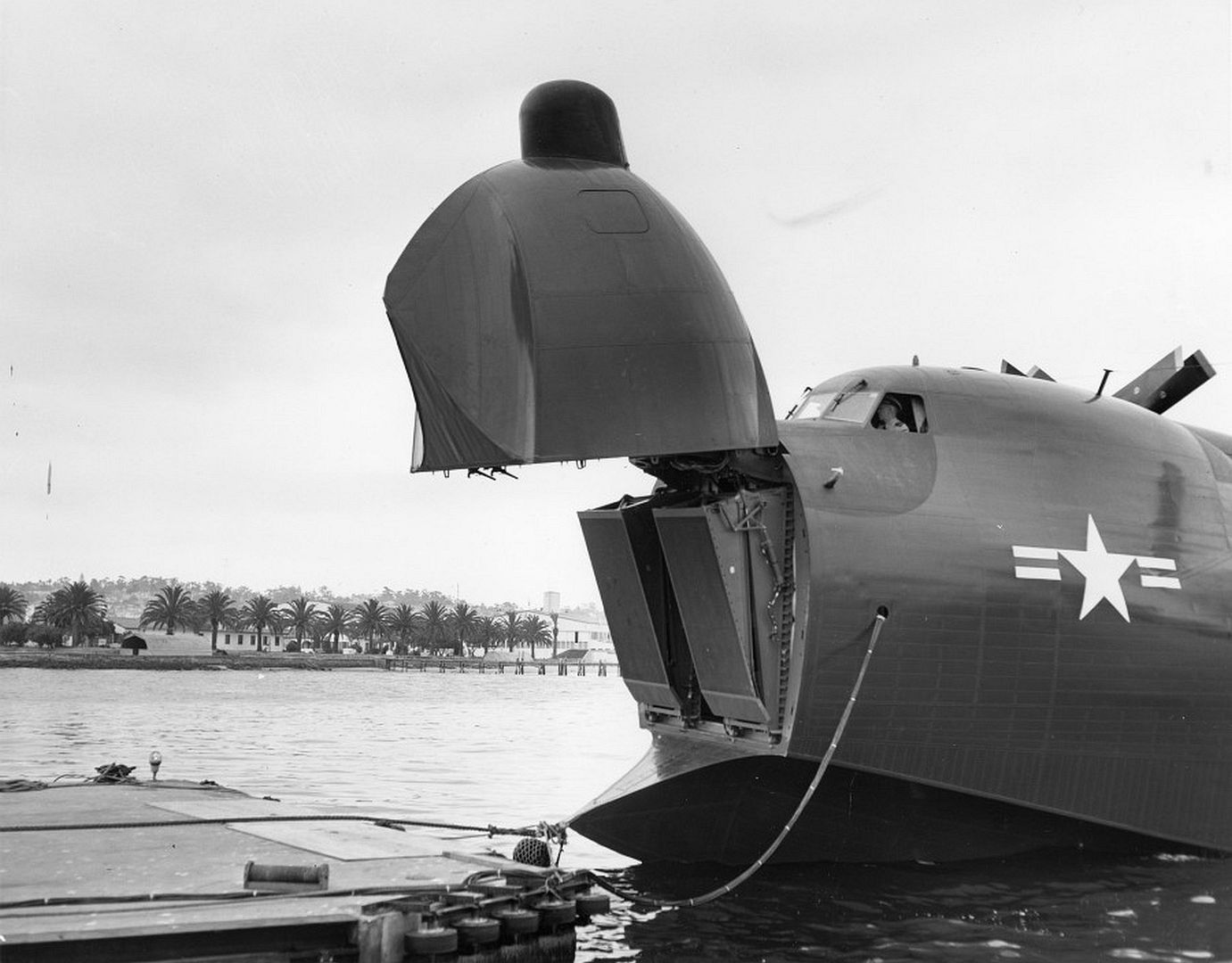

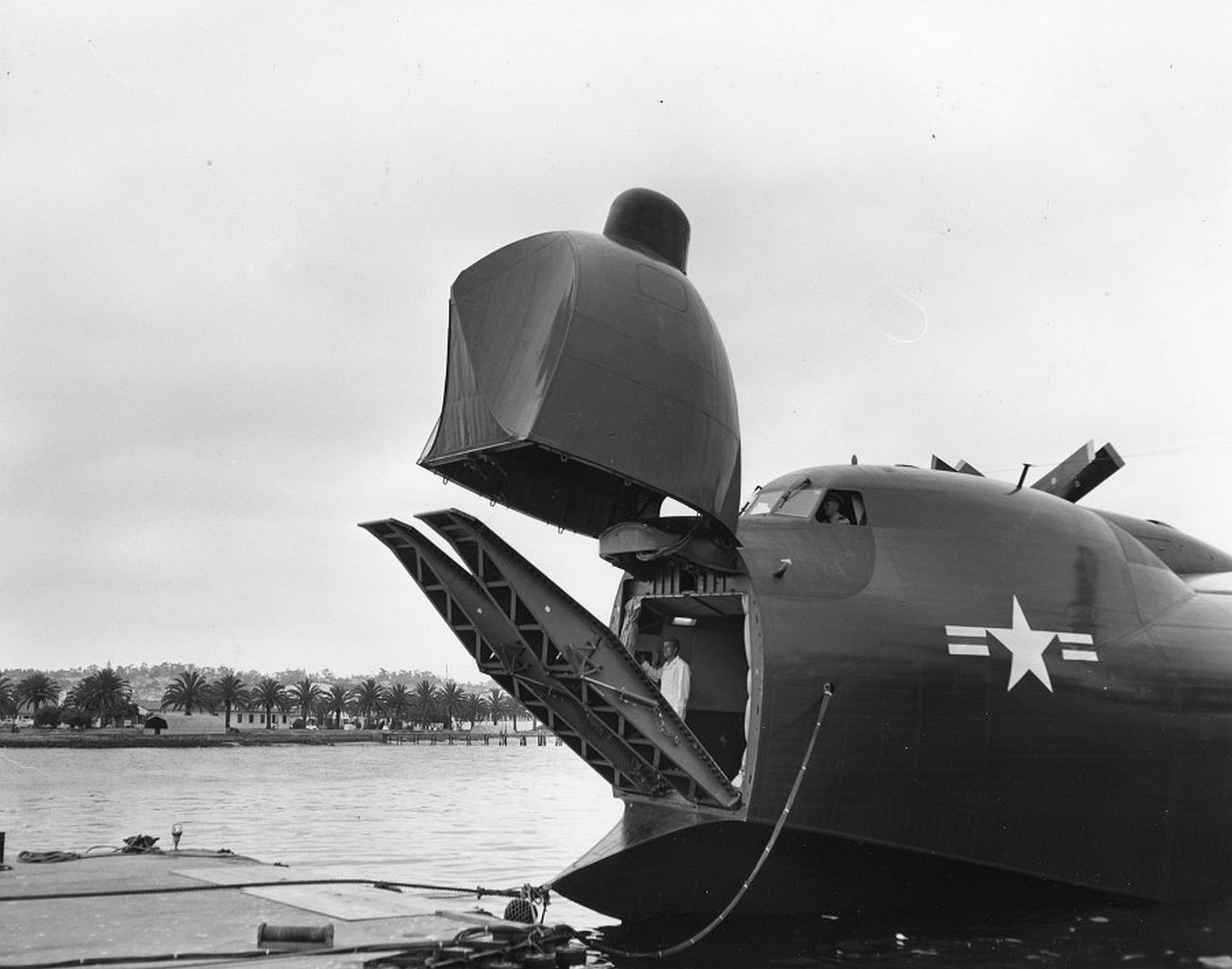

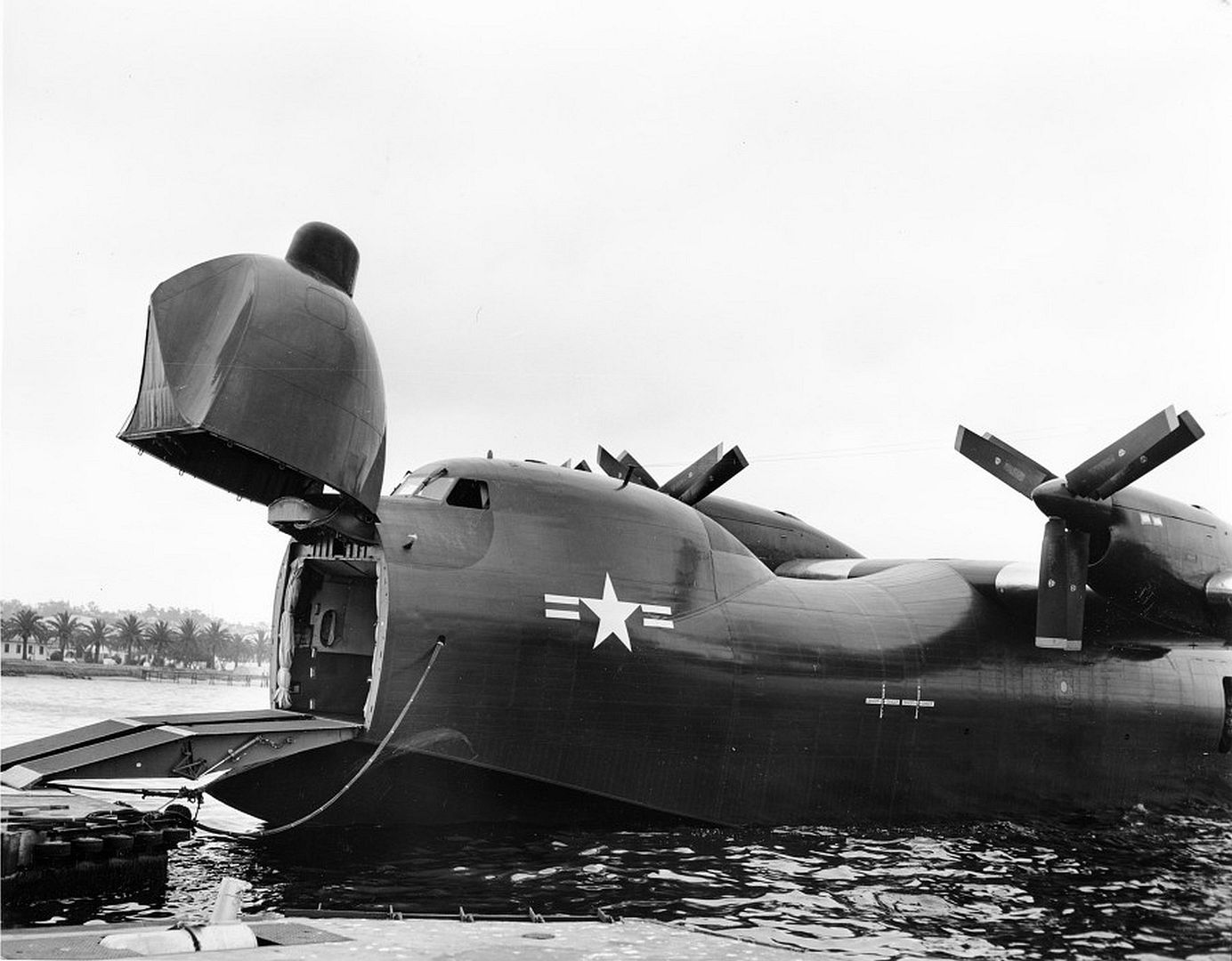

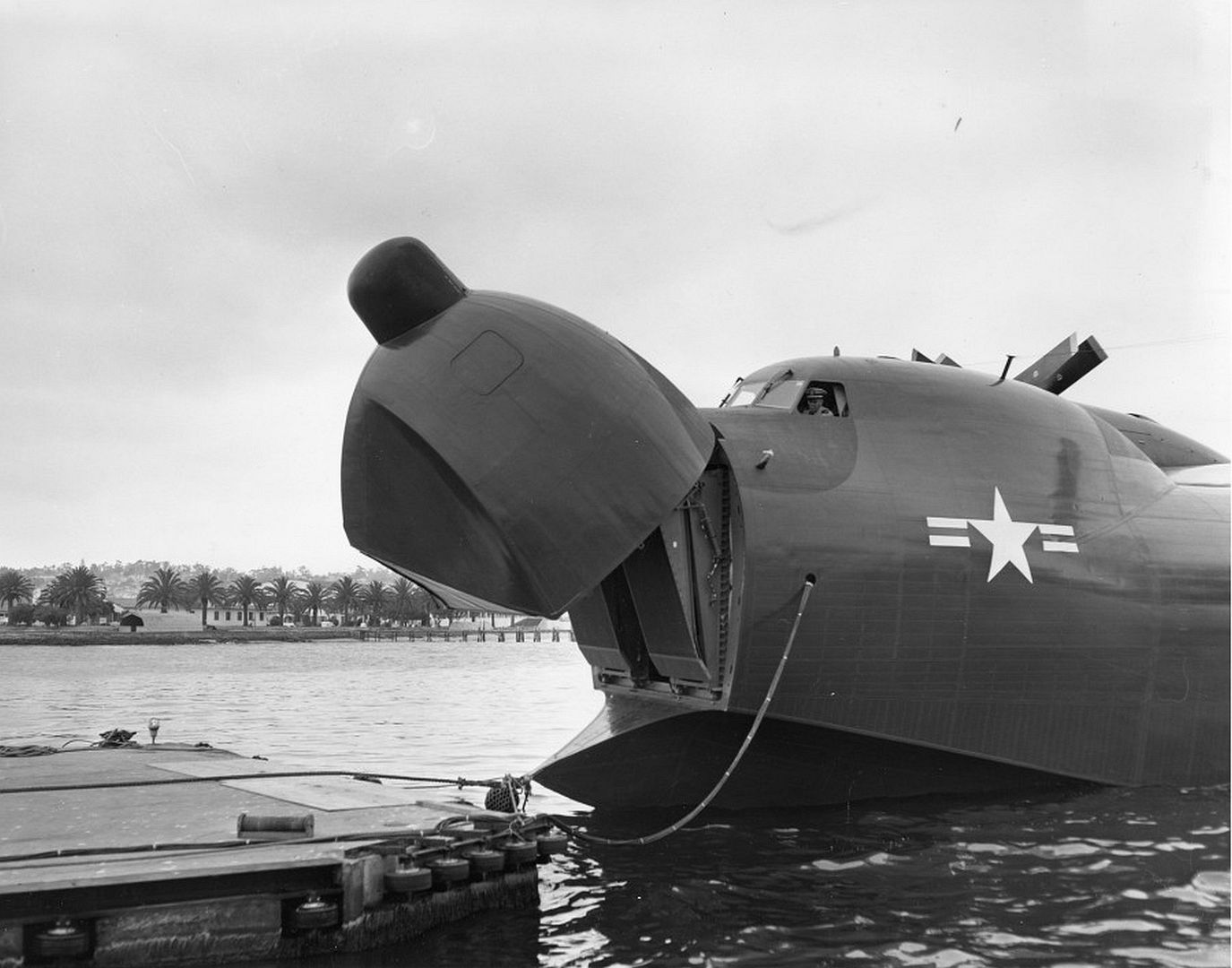

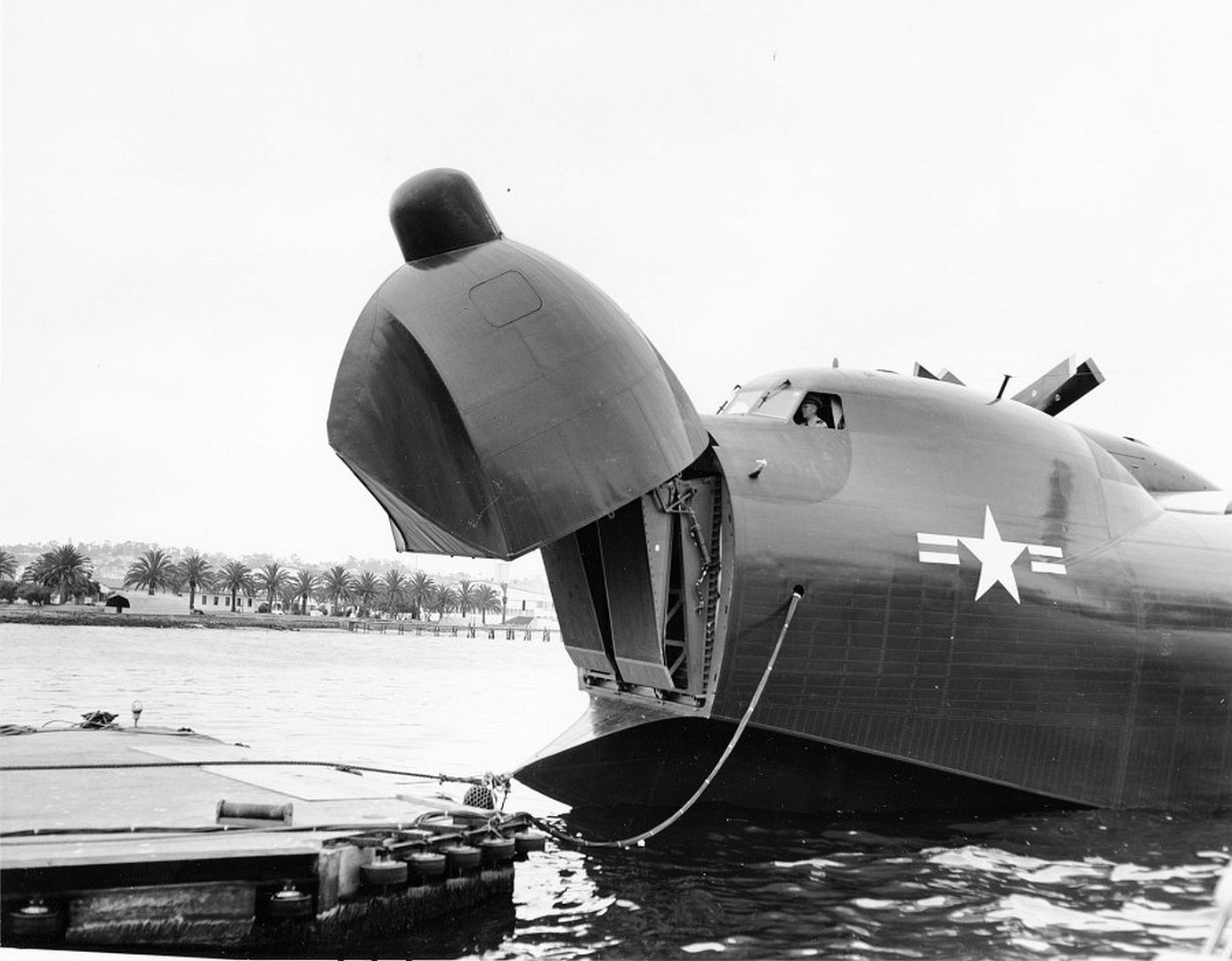

The XP5Y-1 prototype first flew on 18 April 1950 in San Diego. In August of that same year the XP5Y-1 set a turboprop endurance record of 8 hours 6 minutes. Due to the delay in design and construction of the prototypes, the initial patrol boat mission was no longer valid. The Navy instead requested a passenger/cargo version be created to replace the Military Air Transport Service’s Martin Mars seaplanes. This version would be designated the R3Y. Convair returned with two new designs, the R3Y-1 was a passenger transport aircraft with a side loading door and the R3Y-2 was an assault/cargo aircraft with an upward-opening nose loading door similar to the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy. The transport/cargo variants had all armament removed, sported a lengthened fuselage, redesigned engine nacelles (moving them atop the wing rather than within), the addition of cabin soundproofing and pressurization, air conditioning and an additional ten foot wide port-side access hatch.

The R3Y achieved a maximum takeoff weight of 165,000 pounds. It had a length of 139-ft 8-in, stood 51-ft 5-in tall and had a wingspan of 145-ft 9-in which is similar in size to the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. It sported a thin 15:1 beam ratio which allowed it to slice through the water similar to a high-speed boat.

The Tradewind’s twin hull assembly weighed 1,000,000-lbs and had four work levels during assembly. 65,000 specialty tools were required to construct the aircraft. The R3Y-1 had 77 bulkheads (all located below the cargo deck) with some weighing 800-lbs.

The R3Y was designed to carry 100 passengers, 24 tons of cargo, or 92 stretchers with a 2,000 mile range. With 24 tons of cargo capacity, the R3Y-2 could carry four 155-mm towed howitzers or six jeeps or three 6x6 2Vi-ton trucks. Convair intended to market the R3Y-2 as a flying LST (landing ship, tank) as naval LST ships were crucial to many battles in World War II. However, in testing it was determined that pilots could not hold the Tradewind steady enough to nose on to the beach and deploy the vehicles and personnel safely.

In February of 1953 the Navy ordered five R3Y-1 troop transports and six R3Y-2 cargo aircraft. Meanwhile, testing continued of the XP5Y-1 prototype. Forty-two flights with more than 100 flight hours occurred before a non-fatal accident claimed the first prototype on 15 July 1953. While completing contracted testing at 115% of the design limits the elevator torque tube failed and the aircraft began to oscillate through a series of near-vertical dives and climbs. The crew attempted to recover the aircraft for almost 25 minutes before bailing out. The second XP5Y-1 prototype never flew. It was quietly discarded near in 1957.

The R3Y-1 was officially revealed on 17 December 1953, the 50th anniversary of Wright Brothers first flight, but it’s first flight wasn’t until 25 February 1954. The R3Y-2 soon followed on 22 October 1954. Seven of the eleven R3Y Tradewinds built were named for major bodies of water. The fourth-built R3Y, named the “Coral Sea”, set a transcontinental seaplane record of 403 mph that same year by utilizing the speed of high-altitude jetstream winds. The Tradewind flew from San Diego, California to Patuxent River, Maryland in six hours. This record still stands today.

The “Coral Sea” remained at Patuxent River for six months where it conducted thirty test flights including dropping paratroopers from Fort Bragg, North Carolina and the longest flight of nine hours and six minutes. Three additional Tradewinds made the flight to Patuxent River for testing over the following two years.

All aircraft were delivered to USN Air Transport Squadron Two (VR-2) based at NAS Alameda, California starting 31 March 1956 through 28 November 1956. The Tradewind was replacing the unit’s Martin Mars flying boat, the only seaplane larger than the Tradewind. The unit was tasked with flying between San Diego, California and Oahu, Hawaii. The first Tradewind to be delivered was the final built, a R3Y-2 model, and was named the “South Pacific.”

In September of 1956 two R3Y-2 aircraft were modified as in-flight refueling tankers. The first trials were conducted using McDonnell F2H Banshees from VF-23 at NAS Moffett Field, California. The converted Tradewind was the first in-flight refueling aircraft to successfully refuel four other aircraft simultaneously when four Grumman F9F Cougars from VF-111 at NAS North Island, California connected at the same time. The in-flight refueling trials went so well that all remaining Tradewind aircraft were slated for conversion. Ultimately only one additional R3Y-2 and two R3Y-1 aircraft were converted prior to the aircraft’s retirement.

Beginning of the End

The Tradewind’s short service life can be directly attributed to the unreliability of the Allison T40. The T40 engines experienced power deficiency at altitude with poor balance between the dual power sections. Coupled with the 15-ft 1-in diameter propellers and long drive shafts this caused the props to oscillate, overheat and go out of sync. Two problems arose from this condition, gearbox failures and more alarming propeller failure in flight.

In June of 1956 the Tradewind “Caribbean Sea” lost her number one prop while 175 miles off the California coast. The crew was able to continue to Alameda where a safe, three engine landing was completed. Then in May of 1957 the Tradewind “Coral Sea,” of transcontinental seaplane record fame, experienced a runaway number three engine during a training flight. The crew returned to Alameda and attempted a normal landing but found the aircraft to be uncontrollable under 180 knots. The captain elected to perform a 200 knot landing which resulted in a large hole developing in the hull and the aircraft sank in the bay. The famous aircraft was stripped of salvageable equipment, refloated and subsequently scrapped.

Troubles with the T40 occurred so often that maintenance personnel developed a special stand allowing removal of the engine and prop assembly in just 15 man hours. Previously two craning operations were required. With reliability lacking, plans to extend the San Diego to Oahu service on to the Philippines was cancelled.

The penultimate mishap involved another famous Tradewind known as the “Indian Ocean.” This aircraft set a Honolulu to Alameda record of 6 hours 45 minutes. This bested the current record held by the aircraft it replaced, the Martin Mars, by an astonishing 3 hours 46 minutes. Sadly, this aircraft was also lost in an engine-related mishap which occurred on 24 January 1958 when the “Indian Ocean” was completing a night flight from Honolulu to San Francisco. Over 350 miles off the coast of California, the number two engine’s gearbox failed and the propeller suddenly sheared off, slashing the fuselage just forward of the left wing. The crew completed an emergency landing in San Diego only to find that the number one engine controls were cut by the failed prop and it remained fully throttled up. The uncontrollable engine veered them into the seawall. The “Indian Ocean” went out on a high note securing a new Honolulu to Alameda record of 5 hours 54 minutes, bettering it’s previous record while severely damaged by 51 minutes!

All R3Ys were grounded by the end of January 1958. In an effort to salvage the program, Convair proposed replacing the engines with a more reliable Rolls-Royce turboprop (something they also suggested near the start of the program). The eleven aircraft compiled only 3,302 flight hours an average of just over 132 hours (12 hours per aircraft) per month they were in service.

Tradewinds Sunset

Despite the Navy’s critical need for tanker capabilities, the abysmal engine/propeller reliability lead to the termination of the Tradewind operations on 16 April 1958 when Air Transport Squadron VR-2 was decommissioned. All remaining aircraft were officially stricken in March of 1959. Late that year an order was issued to cut the vertical fins off the grounded and stricken aircraft as if just seeing them was a painful embarrassment. The final R3Y was cut up and hauled away by rail in the spring of 1960.

Ironically, and sadly, the last remnants of Convair’s massive, short lived sea plane are a few of the troubled Allison T40 engines in museums. For 25 months of service, the Navy had expended over $250 Million in design and production costs. This amount does not include the operational and replenishment costs of such a maintenance hungry aircraft.

Variants

XP5Y-1 - Prototype patrol flying boat, two built.

R3Y-1 - Transport aircraft for the United States Navy with side loading door, 5 built.

R3Y-2 - Assault transport aircraft for the USN with shorter nose incorporating an upward-opening loading door.

Later converted to four-point tankers for probe-and-drogue operations, six built._123_in_1956-1.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)

_123_in_1956-3.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)

_123_in_1956.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)

_123_in_1956-2.jpg?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)

Specifications (R3Y-1)

General characteristics

Crew: 7 flight crew + cabin crew / loadmasters

Capacity: 80 pax / 72 litter patients with 8 medical staff

R3Y-2: 103 pax / 92 litter patients with 12 medical staff

Length: 139 ft 8.3 in (42.578 m)

R3Y-2: 141 ft 1.7 in (43 m)

Wingspan: 145 ft 9.7 in (44.442 m)

Width: 12 ft 6 in (3.81 m) maximum hull beam

Height: 49 ft 0 in (14.94 m) keel to fin tip

51 ft 5.2 in (16 m) on beaching gear

Wing area: 2,100.7 sq ft (195.16 m2)

Aspect ratio: 10

Airfoil: root: NACA 1420 ; Mid span NACA 4417 ; tip: NACA 4412 ; average thickness 18%

Gross weight: 145,500 lb (65,998 kg)

Max takeoff weight: 165,000 lb (74,843 kg)

Landing weight: 136,739 lb (62,024 kg) with maximum cargo

Fuel capacity: 66,000 lb (29,937 kg)

Powerplant: 4 × Allison T40-A-10 turboprop engines, 5,332 shp (3,976 kW) each

Propellers: 6-bladed Aeroproducts, 15 ft (4.6 m) diameter contra-rotating fully-feathering reversible propellers

Performance

Maximum speed: 299 kn (344 mph, 554 km/h) at 21,000 ft (6,401 m) at MTOW

308 kn (354 mph; 570 km/h) at 23,000 ft (7,010 m) at normal gross weight

Cruise speed: 300 kn (350 mph, 560 km/h) average at 29,000–34,200 ft (8,839–10,424 m)

Stall speed: 98 kn (113 mph, 181 km/h) at MTOW power off

89.4 kn (102.9 mph; 165.6 km/h) at 136,739 lb (62,024 kg) power off

87.5 kn (100.7 mph; 162.1 km/h) at 136,739 lb (62,024 kg) with approach power

Range: 2,420 nmi (2,780 mi, 4,480 km)

Combat range: 1,240 nmi (1,430 mi, 2,300 km)

Service ceiling: 30,300 ft (9,200 m) at MTOW

Rate of climb: 1,910 ft/min (9.7 m/s) at MTOW

Time to altitude: 20,000 ft (6,096 m) in 12 minutes 18 seconds at MTOW

30,000 ft (9,144 m) in 43 minutes 12 seconds

Wing loading: 78.5 lb/sq ft (383 kg/m2) at MTOW

Power/mass: 0.1293 hp/lb (0.2126 kW/kg) at MTOW

Take-off time: 50 seconds in calm sea conditions at MTOW

Text from here by Sean Sims. - http://www.thehangardeck.com/news/2019/4/8/the-short-storied-history-of-the-convair-xp5yr3y-tradewind

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources