Forums

414th NFS

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

13 years ago

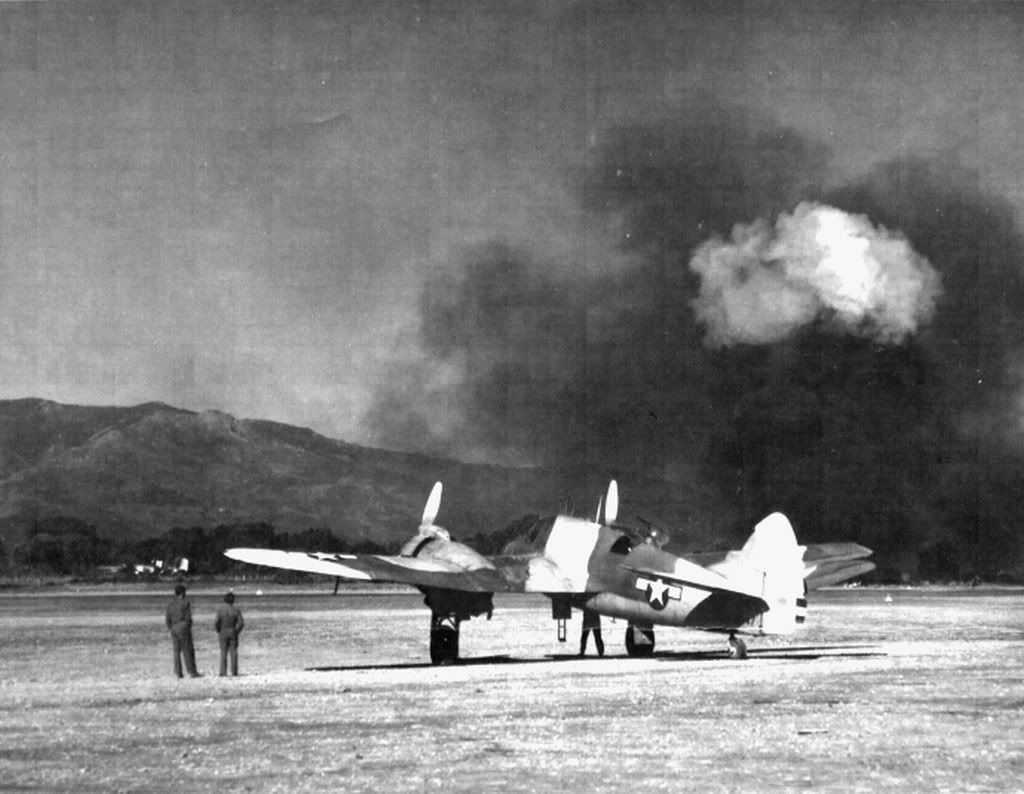

Main AdminThe first U.S. night fighter unit was the 1st Pursuit Squadron (Night), formed from the 15th Bombardment Group (Light) in March 1942 after AAF Commanding General Henry H. (Hap) Arnold?s representative in England asked for a fighter unit, to be equipped with Britishprovided Turbinlite aircraft. Having arrived in England in May 1942, the 1st Squadron soon reverted to the 15th Bomb Group (Light) because of the failure of British Turbinlite operations. The 15th went on to launch the United States? first bombing strike against German targets on July 4, 1942, flying borrowed British Boston IIIs-by day.

Main AdminThe first U.S. night fighter unit was the 1st Pursuit Squadron (Night), formed from the 15th Bombardment Group (Light) in March 1942 after AAF Commanding General Henry H. (Hap) Arnold?s representative in England asked for a fighter unit, to be equipped with Britishprovided Turbinlite aircraft. Having arrived in England in May 1942, the 1st Squadron soon reverted to the 15th Bomb Group (Light) because of the failure of British Turbinlite operations. The 15th went on to launch the United States? first bombing strike against German targets on July 4, 1942, flying borrowed British Boston IIIs-by day.

Meanwhile, the 414th and 415th NFS became the first graduates of the hastily organized training program at Orlando, having flown P-70s and Link trainers. After their transfer to England in late March 1943, the squadrons gained additional training from experienced British units. While there, they practiced night flying in Blenheims left over from the Battle of Britain before converting to Beaufighters and giving up the P-70s in which they had trained in the States. The P-70 proved too slow in climbing to operational altitudes (45 minutes to 22,000 feet) and performed poorly at high altitudes. Several veteran U.S. pilots already flying with the RAF joined the 414th and 415th before they moved to North Africa for combat in July 1943. Two new squadrons from Orlando, the 416th and 417th, then replaced the 414th and 415th in England.

Plans for Operation TORCH, the invasion of North Africa, gave shipping priority to offensive aircraft, delaying the arrival of night fighter units. After Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower reported that he was ?gravely concerned? about the lack of night protection, veteran British units were rushed in to fill the void. Only two days after arriving on the scene, British Beaufighters made their nighttime presence felt, downing eleven out of thirteen attacking Luftwaffe bombers. In part, British success could be attributed to the advanced microwave Mark VIII airborne radar, which did not suffer from the range limitations of the Mark IV/SCR-540 airborne radars that equipped U.S. Beaufighters. Over the next few months, more British night squadrons were deployed to North Africa before the first U.S. squadron, the 414th, arrived in June 1943. The 415th NFS joined these American pioneers during the summer.

Temperatures of 130 degrees in the shade and a constant shortage of replacement parts were only two of the obstacles ground crews faced in keeping the Beaufighters flying. Friendly fire from jittery Allied ground gunners increased the dangers of night flying. Yet, relying primarily on British ground control radar, U.S. crews soon began to score aerial victories, with the first one credited to Pilot Capt. Nathaniel H. Lindsay and R/O Flight Officer Austin G. Petry of the 415th NFS on July 24, 1943. Unfortunately, excessive ground clutter displayed on the Mark IV airborne radars held the 414th and 415th?s Beaufighters to four kills by the end of the North African campaign. The 416th and 417th squadrons eventually joined Twelfth Air Force, but flew unproductive convoy and harbor patrols. The 417th?s opportunity came on October 22, 1943, when ground control radar vectored the newest U.S. night fighter squadron to twenty German aircraft, but the Beaufighters? Mark IV airborne radars proved unable to maintain contact.

Critical to a successful intercept were two factors: speed and ground control radar. 2d Lt. Daniel L. McGuire, a veteran of seventy-five combat missions, explained that ground control radar was useful up to only about sixty miles from the transmitter site. Because the antiaircraft artillery zone defending the site had a radius of fifteen miles, night fighters had only the forty-five miles outside the ground fire zone to the limit of ground control radar range to locate, track, and down an intruder. At speeds of 250 miles per hour, the pursuers had only ten minutes to do their deadly job. It took nearly that long to reach operational altitudes, so there could be no scrambling of fighters once an enemy appeared on the ground control radar screen. Night pursuit aircraft would have to be at altitude, orbiting and waiting, when a bogey appeared.

The ground control radar station used a cathode ray tube designated a Plan Position Indicator to plot the paths of aircraft within radar range. Aircraft appeared on the tube as little blips of light, with identification friend or foe (IFF) radio transmissions identifying the night fighter that the ground control radar operator, or fighter controller, was trying to vector to an interception point. Using VHF radio, the controller directed the night fighter to a point several miles to the rear of the intruder. (A serious limitation of the system was that each ground control radar could control only one night fighter at a time.) Once the airborne R/O made contact with the enemy on his radar set, he directed the pilot to a location where visual contact could be made, at which point the pilot took over. Visual contact was needed to aim the guns and to insure visual recognition of the target, as required by the rules of engagement. Until then, it was a matter of blind faith, with the pilot relying on the R/O behind him to direct an intercept. Though the pilot usually had a radar screen in the cockpit, he dared not look at it for fear of ruining his night vision. Surprise was essential. An enemy using evasive maneuvers was difficult to shoot down. Surprise an enemy at two or three hundred feet ?and open fire with four 20-mm cannons,? according to 2d Lt. Robert F. Graham, ?and that was it.?

Obviously, teamwork was critical. The ground control radar fighter controller could see things the airborne crew could not. The rule in most squadrons was ?no night fighter unit is any better than its control.? Pilot and R/O combined two pairs of eyes, each having a separate responsibility. The pilot had to make smooth consistent turns, whether hard or gentle, or the R/O, with his eyes focused on a small scope, would become confused. According to the wartime commander of the 422d NFS, Maj. Gen. Oris B. Johnson (Ret.), there was no fear of collision, no use of intuition, and no flying by the seat of your pants. Johnson and his R/O, Capt. James ?Pop? Montgomery, flew together from August 1942 until the end of the war. They became so much a team that Johnson could always tell when Montgomery had made airborne radar contact because ?he began to breathe hard.? Proof of the importance of teamwork was a mission in which Montgomery kept Johnson on the tail of a bogey for fifteen minutes, though the pilot never made visual contact. Johnson?s oxygen mask had pulled loose, blurring his vision. The team as a whole was greater than the mere sum of its two parts.

Ground control radar technology alone could not provide accurate altitude directions, so the night fighter had to check out various altitudes, making speed essential for intercepting an intruder before he reached the antiaircraft artillery fire zone. On the other hand, airborne radar was dependable at a distance of several miles. If the night fighter approached too fast, it would probably overshoot the target, requiring the use of speed brakes at about four thousand feet from the target. Too slow an approach and the target might enter the ground fire zone or move beyond airborne radar range. Stateside training taught that the proper technique was for the pursuer to synchronize his speed with the target?s speed and close slowly, but pilots in combat soon discovered that such a tactic took too long and too often allowed the target to escape.

Another stateside lesson involved using exhaust flame patterns to identify the targeted aircraft. One pilot who received such ?extensive training? in flame pattern recognition techniques reported that after eighteen months of combat operations in Europe, he had never seen the exhaust of a German plane that was not entirely blacked out by flame dampeners. This training technique was not a total waste, however, because if a suspect aircraft did show exhaust flames, it was usually American. The best method for identifying the target, according to combat returnees, was to silhouette it against the sky from below and identify it by shape and size. A bonus of this technique was invisibility, because if the enemy was using radar, he would be blind to an approach from below.

A night fighter pilot followed his R/O?s directions to get within visual distance, usually 750 feet or less. Some veterans learned that if they could not make visual contact, a trick of the trade was to fire the aircraft?s cannons blindly, hoping the bogey would open fire, revealing his presence. As one pilot reported, ?the practice is admittedly risky but at times has proven effective.? The riskiest practice, however, was following an intercept into the antiaircraft artillery zones-enemy or Allied. To a man, night fighter combat veterans agreed that the biggest threat they faced was Allied ground fire. Having the ground control radar fighter controller also in charge of antiaircraft artillery fire helped, but friction between the ground artillery and airmen usually prevented any effective cooperation.

During the invasion of Italy in September 1943, the four U.S. night fighter squadrons began to reequip with the SCR-720 airborne microwave radar, though security concerns restricted it from use over enemy-held territory, and it was not released for general use until May 1944. The new radars raised morale but did not bring better hunting. 417th NFS crews did not get their first SCR-720 kill, a Ju 88 downed while on convoy duty, until early February 1944. The continuing lack of opportunities encouraged the 417th?s historian to write ?at last? when the squadron racked up its next aerial victory in late March. Victories were hard to come by, especially because the RAF did most of the night flying. Over Anzio the 415th claimed only two confirmed kills in three months of operations. Its crews reported they were ?fired on by friendly flak more than by enemy flak.? In April 1944 the 416th NFS replaced the 415th because their Beaufighter Mark VIII airborne radar sets proved less susceptible to the window/chaff German pilots had begun using in large quantities. The 416th NFS did little better than the 415th, despite the advanced radar, because of a lack of aerial targets. In 542 missions from January 28 to May 25, 1944, including two months over Anzio, the 416th achieved only thirty-three airborne radar contacts, resulting in two kills.

All four U.S. night fighter squadrons found poor hunting in the Mediterranean theater. Night after night the Beaufighter-equipped 417th NFS, newly arrived at Corsica, rose and found the skies empty, except for one unlucky German off Spain in March. On the night of May 12/13, 1944, however, the Luftwaffe launched a heavy strike against Allied bases at Alesan and Poretta, Corsica, damaging or destroying over one hundred B-25s on the ground and killing or seriously wounding ninety-one personnel. The attacking He 177s proved too fast for the 417th?s Beaufighters, which claimed only one probable kill. The 414th, 415th, and 417th flew night cover for the invasion of southern France, but again the major threat they faced was trigger-happy Allied gunners on the ground. With Allied troops ashore, the 414th and 417th returned to intruder work in Italy, while the 415th flew night cover for the American Seventh Army?s drive north through France.

Even when the night fighters found targets and hit them, the results were not always guaranteed. On May 14, 1944, the 416th NFS ordered Capt. Harris B. Cargill and R/O Flight Officer Freddie C. Kight into the air at 0335 hours to intercept a German intruder. Kight needed twentyfive minutes of ground control radar guidance before locating the bogey on his airborne radar. Identification friend or foe transmissions identified the target as an enemy aircraft, which then initiated evasive maneuvers and dropped window/chaff. Still, the rules of engagement required visual identification. Fifteen minutes of maneuvering brought Cargill into visual contact four hundred feet from the target. Two hundred rounds of 20-mm and 1,260 of .50-caliber fire forced the Ju 88 into a violent dive toward the ground. In night combat, however, especially with clouds, verification of a kill was tough. The bogey disappeared from ground control radar and airborne radar screens, and ground troops reported seeing a German aircraft flying very low before it ?disappeared towards water.? The Victory Credit Board refused to grant Cargill and Kight a victory.

Posterity will never know exactly how many aircraft were shot down by U.S. night fighters. Theirs was a lonely war. Claims had to be substantiated, which was usually not possible at night. A ground control radar operator could help, confirming that a bogey disappeared from his screen at the time claimed by the night fighter crews. R/O 1st Lt. Robert E. Tierney of the 422d NFS remembered his pilot, 1st Lt. Paul A. Smith, radioing ?Murder! Murder! Murder! Give me a fix!? to his ground control radar fighter controller after a kill. Smith then climbed to a higher altitude, orbiting the spot of the victory, so the controller could plot the location. The next day a reconnaissance aircraft would fly to the plotted position, if one were available, and attempt to photograph the downed enemy plane. But Tierney, Smith, and the rest of the night fighter crews were in a war that could not be stopped to tally victory credits.

Britain?s decision to stop building Beaufighters after January 1, 1944, condemned many U.S. night fighter pilots in the Mediterranean theater to flying war-weary aircraft that were already three years old by 1944. The 414th got P-61s and the 416th Mosquitoes in late 1944, while the 415th and 417th soldiered on with the venerable Beaufighter (some of which had fought in the Battle of Britain), though the latter had the highest accident rates in the theater. Nevertheless, with RAF units, U.S. night fighters forced the Luftwaffe into single aircraft ?nuisance? raids during the Italian campaign. Flying at low altitudes to hide their presence from airborne or ground radars and using radar jamming and window/chaff to confuse Allied ground control radars, the occasional German reconnaissance flight offered no aerial threat to Allied operations.

By mid-1944 Allied daylight air superiority had so weakened the Luftwaffe that it was forced into mostly night operations. U.S. night fighter squadrons flew missions to stop these nocturnal ventures, yet the vast majority of radar contacts proved to be Allied aircraft. In the words of the men searching for German bogeys, ?none seemed anxious to press the attack.? Anxious to contribute to victory, the night fighters had to find a new way to wage war. The British had initiated just such a new mission for night fighters back in June 1940.

Night intruder missions were the brainchild of Flight Lt. Karel M. Kuttelwascher, a Czech pilot who had escaped to France in 1939. Committed to attacking Nazis, he found defensive patrols too passive. Initially he proposed using night fighters in a counterair role, striking against enemy night air power at its source-German airfields. On an early mission, Kuttelwascher shot down three German bombers in five minutes. Then, on another sortie, he claimed eight bombers that crashed because his presence prevented them from landing and refueling. Emulating their Czech comrade, RAF night crews, flying U.S.-built Bostons, endeavored to shoot down German bombers returning to their bases after missions against England, just as the crews turned on their landing lights. British intruders also began strafing trains on their return flights to England. Pouncing on the unsuspecting victim so close to home, where the enemy felt most secure, had a dramatic effect on Luftwaffe morale. Many of these British nighttime missions also supported Bomber Command operations, attempting to suppress German night fighters as they rose to intercept the bomber streams.

In 1944 U.S. units expanded on this role of night intrusion. If the enemy would not come up and expose himself to aerial combat, AAF night fighters would follow the British lead and attack him at his airfields. Moreover, when German ground forces used the cover of darkness for maneuvering and resupplying to avoid the overwhelming Allied air superiority in the day, the night fighters attempted to harass them in the starlit skies. These operations often differed from British intruder missions in that the U.S. night fighters performed armed reconnaissance, flying over enemy territory during darkness with no preplanned targets, in search of targets of opportunity: troop movements, motor transport, shipping, and railroads. These missions were flown in conjunction with day interdiction efforts in order to isolate enemy forces on the battlefield twenty-four hours a day.

Meanwhile, Operation STRANGLE called for interdicting the flow of supplies to Nazi forces in Italy. Its success during the day forced the enemy to travel at night. Night fighters were thrown into the breach, according to a squadron historian, to bridge ?the gap so that the destruction of the enemy air force, the isolation of the battle field, and support of the ground forces, might be put on a 24 hour basis.? Air leaders divided northern Italy into fifty-mile squares, with an aircraft orbiting each square, to be relieved by other aircraft throughout the night. At its peak, this night effort included four A-20 squadrons from the 47th Bombardment Group and the three night fighter squadrons in Italy, the 414th, 416th, and 417th, flying the venerable British Beaufighters. Unfortunately, the operation?s success was difficult to measure. Except for crew reports, these forces lacked the ability to evaluate their effectiveness. Since Germany continued to resupply its troops in Italy by night, despite the most extensive use of interdiction of the entire war, apparently the effort failed, whatever price the night intruders exacted.

Artillery spotting was another job performed by night fighter crews. Flying over enemy lines, they looked for muzzle flashes. After dropping flares on a suspected position, the airmen would descend and attempt to identify the target. When a crew spotted an artillery position, they would radio a gun-laying radar behind American lines, which would mark the aircraft?s position at that moment before directing an artillery barrage to the suspected enemy position.

In eighteen months of operations, using the ground and airborne radar visual recognition technique of night interception, the four U.S. night 26 fighter squadrons in the Mediterranean flew 4,937 sorties, received credit for downing thirty-five enemy aircraft, and in the process lost forty-eight of their own from all causes. These night fighters helped harry enemy aircraft, broke up raids, and lessened German night bombing accuracy. Their successes boosted Allied morale at the expense of Nazi morale. The official AAF history of the squadrons? activities reported that ?their contributions, both toward the outcome of the actual battle and in the experience gained and lessons learned, were invaluable and greatly aided the ultimate Allied victory.? U.S. night fighter squadrons set the tone and provided lessons for future U.S. night aerial activities: avoid bright lights, keep the windscreen spotless and unscratched, turn cockpit lights off, use oxygen from the ground up (combat experience showed an increase in night vision of 40 percent at 16,000 feet with the continuous use of oxygen), and use the corners of the eyes for the best night vision. The Mediterranean Allied Coastal Air Force believed ?it does not suffice simply to practice them [these rules] spasmodically: one must live them constantly if one is to live constantly.? The official history of U.S. night fighter operations in the Mediterranean theater concluded that ?in terms of destruction alone they [the night fighters] had hardly justified their existence. On the other hand, their existence was one of the reasons they had few opportunities to destroy enemy planes.?

Regards Duggy. -

12 years ago

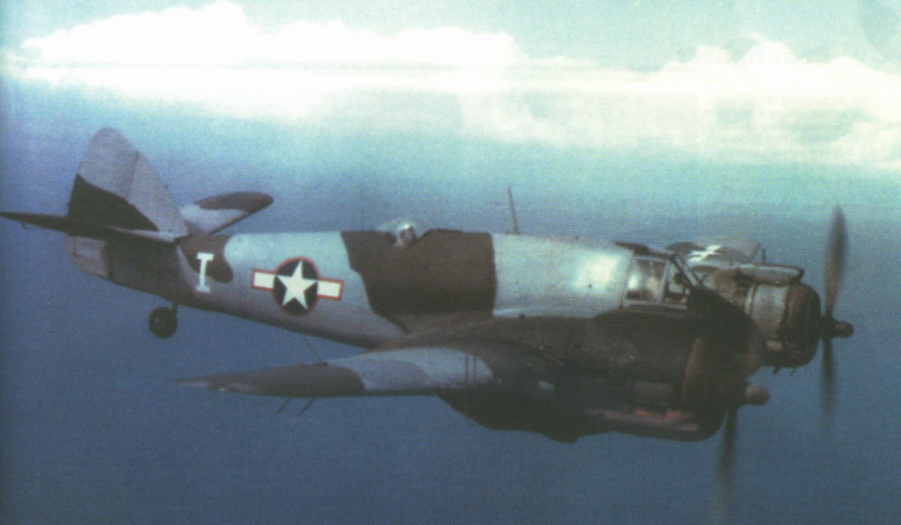

Level 1Here is a nice colour Beaufighter that I'm sure is a 414th NFS aircraft.

Level 1Here is a nice colour Beaufighter that I'm sure is a 414th NFS aircraft.

-

12 years ago

Main AdminThanks Kev an interesting shot, I would imagine taken 43 due too the red surround.

Main AdminThanks Kev an interesting shot, I would imagine taken 43 due too the red surround.

Regards Alan -

AdminAwesome... I'd only ever seen one or two photos of American Beaus- got any more? If I can find the time, I might throw together a few skins...

AdminAwesome... I'd only ever seen one or two photos of American Beaus- got any more? If I can find the time, I might throw together a few skins...

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources