Forums

He-100

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

10 years agoSun Jun 06 2021, 12:05pmDuggy

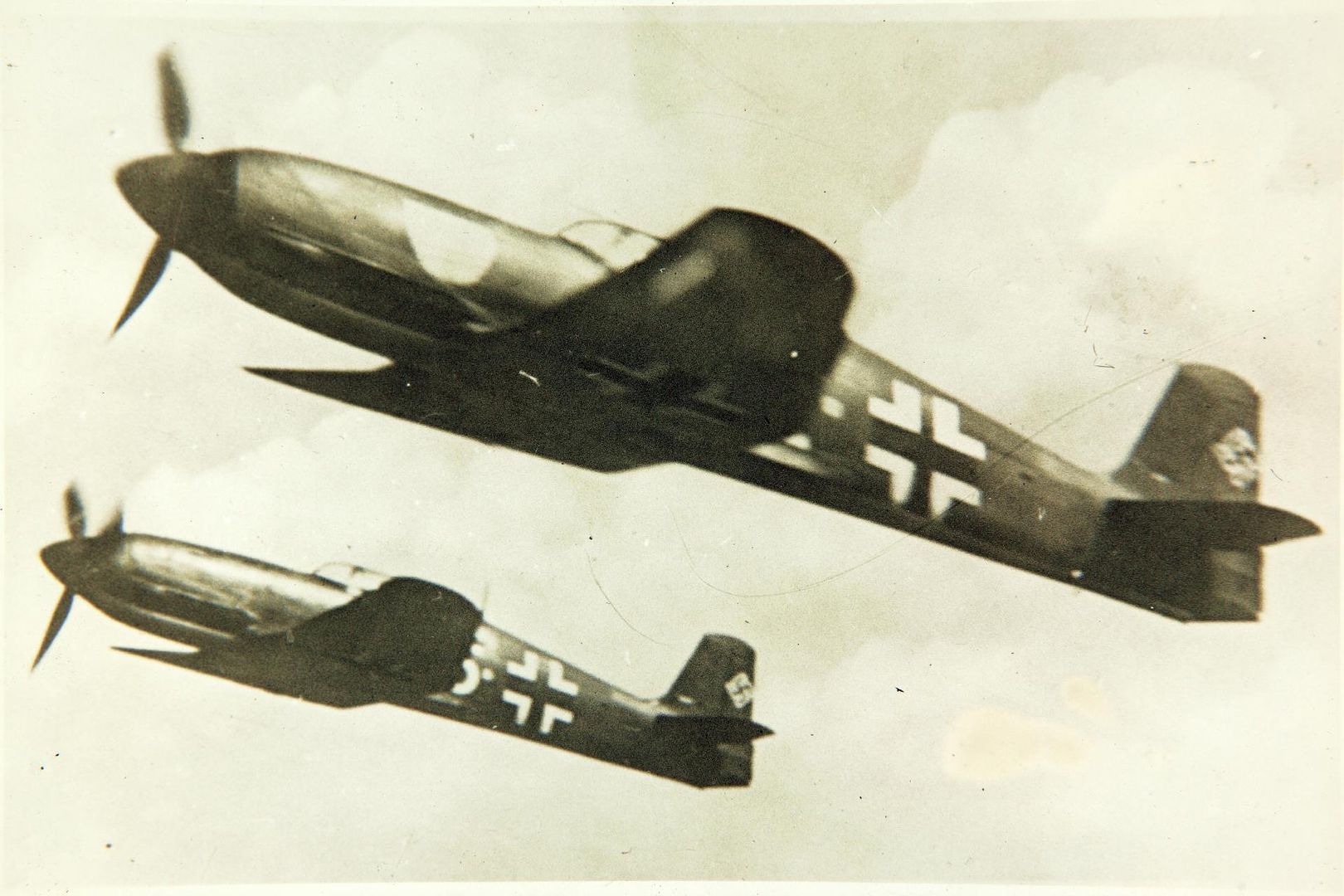

Main AdminThe Heinkel He 100 was a German pre-World War II fighter aircraft design from Heinkel. Although it proved to be one of the fastest fighter aircraft in the world at the time of its development, the design was not ordered into series production, Approximately 19 prototypes and pre-production machines were built. The reason for the failure of the He 100 to reach production status is subject to debate. None are known to have survived the war.

Main AdminThe Heinkel He 100 was a German pre-World War II fighter aircraft design from Heinkel. Although it proved to be one of the fastest fighter aircraft in the world at the time of its development, the design was not ordered into series production, Approximately 19 prototypes and pre-production machines were built. The reason for the failure of the He 100 to reach production status is subject to debate. None are known to have survived the war.

Officially, the Luftwaffe rejected the He 100 to concentrate single seat fighter development on the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Following the adoption of the Bf 109 and Bf 110 as the Luftwaffe's standard fighter types, the RLM announced a "rationalization" policy that placed fighter development at Messerschmitt and bomber development at Heinkel.

Design & Development

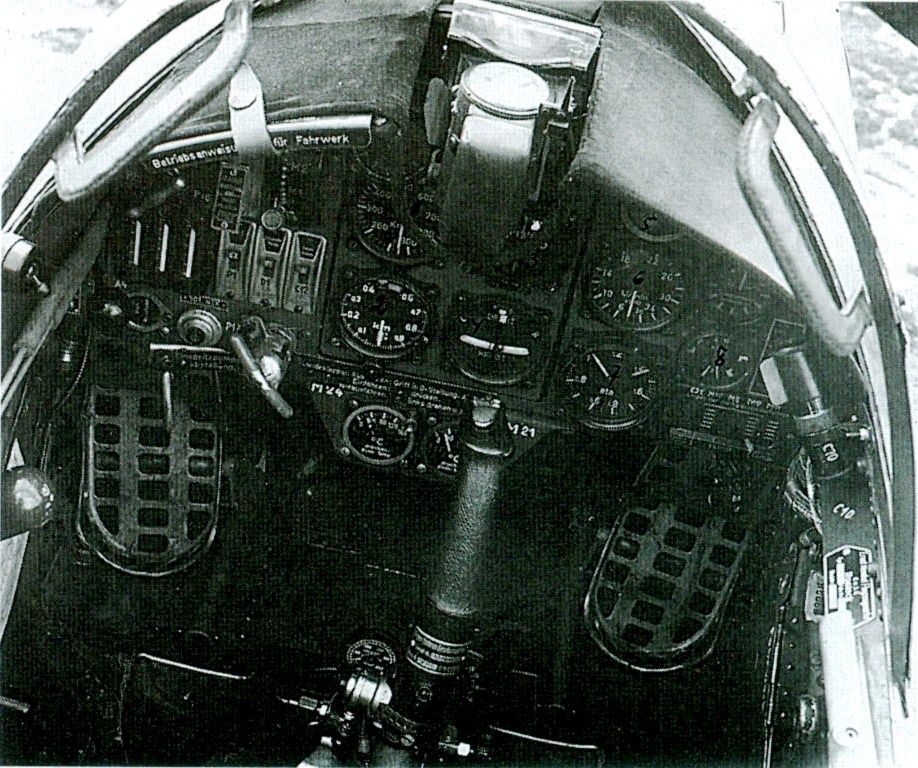

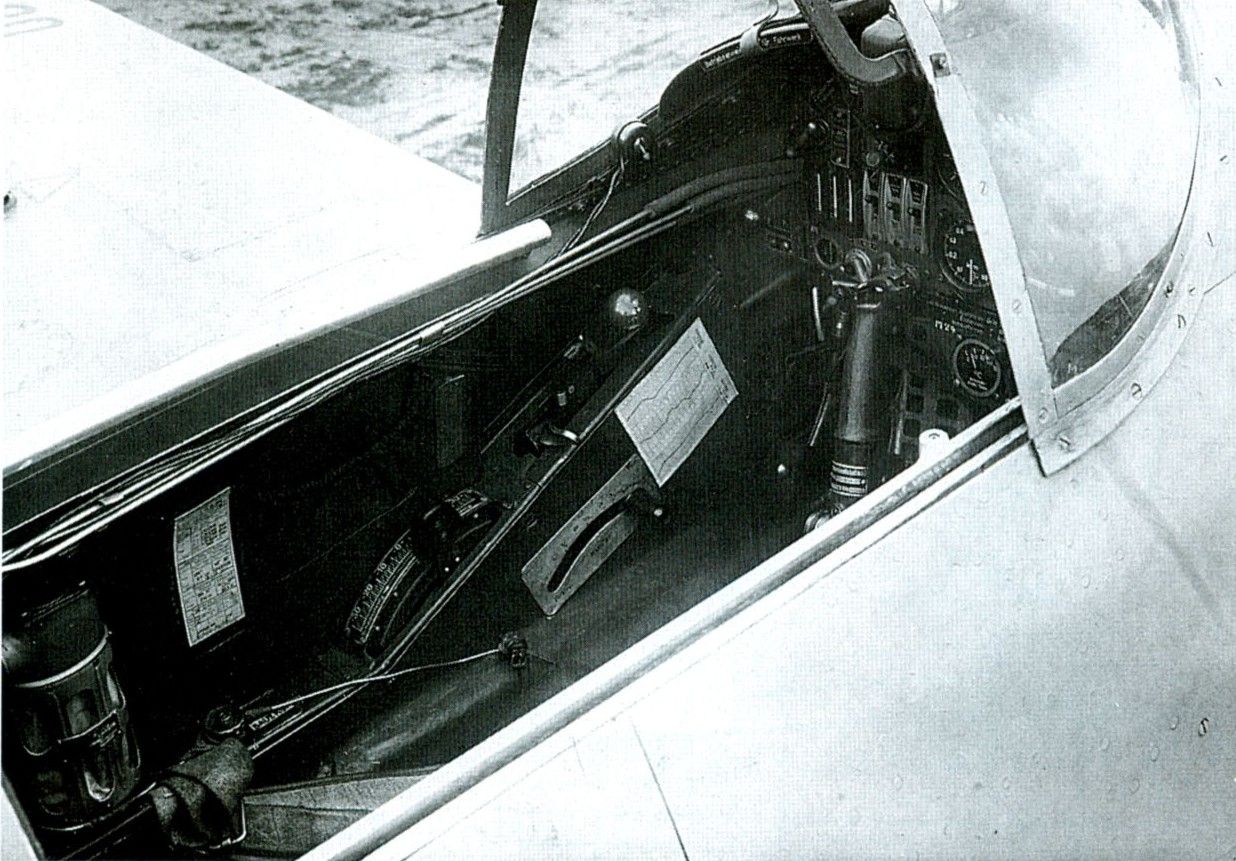

In order to get the promised performance out of the aircraft, the design included a number of drag reducing features. On the simple end was a well faired cockpit, the absence of struts and other drag inducing supports on the tail. The landing gear (including the tailwheel) was retractable and completely enclosed in flight.

There was also a serious shortage of advanced aero engines in Germany during the late 1930s. The He 100 used the same Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine as the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110, and there was insufficient capacity to support another aircraft using the same engine. The only available alternate engine was the Jumo 211, and Heinkel was encouraged to consider its use in the He 100. However, the early Jumo 211 then available did not use a presurized cooling system, and it was therefore not suitable for the He 100's evaporative cooling system. Furthermore, a Jumo 211-powered He 100 would not have been able to outperform the contemporary DB 601-powered Bf 109 because the supercharger on the early Jumo 211 was not fully shrouded. From a practical matter, the He 100 used a novel cooling system that was complex, dependent upon many small pumps and difficult to maintain under field conditions. In order to reduce weight and frontal area, the engine was mounted directly to the forward fuselage, which was strengthened and literally tailored to the DB 601, as opposed to conventional mounting on engine bearers. The cowling was very tight fitting and as a result the aircraft has something of a slab sided appearance.

In order to provide as much power as possible from the DB 601 engine, the 100 used exhaust ejectors for a small amount of additional thrust. The supercharger inlet was moved from the normal position on the side of the cowling to a location in the leading edge of the left wing, which was also a feature of the earlier He-119. Although cleaner looking, the long, curving induction pipe most likely negated any benefit.

For the rest of the designed performance increase, Walter turned to the somewhat risky and still experimental method of cooling the engine via evaporative cooling. Such systems had been in vogue in several countries at the time. Heinkel and the Gunter brothers were avid proponents of the technology, and had previously used it on the He-119 with promising results. Evaporative or "steam" cooling promised a completely drag free cooling system. Unfortunately, the systems also proved complex and terribly unreliable in practice. Huge expanses of the airframe's outer skin had to be devoted to cooling, which made such systems succeptible to combat damage. The DB 601 was a pressure cooled engine in that the water/glycol coolant was kept in liquid form by pressure even though its temperature was allowed to exceed the normal boiling point. Heinkel's system took advantage of that fact and the cooling energy loss associated with the phase change of the coolant as it boils. Following is a description of what is known about the cooling system used in the final version of Heinkel's system. It is based entirely on careful study of surviving photographs of the He 100 since no detail plans survive. The earlier prototypes varied, but they were all eventually modified to something close to the final standard before they were exported to the Soviet Union.

Coolant exits the DB 601 at two points located at the front of the engine and at the base of each cylinder block casting immediately adjacent to the crank case. In the Heinkel system, an "S" shaped steel pipe took the coolant from each side of the engine to one of two steam separators mounted alongside the engine's reduction gear and immediately behind the propeller spinner. The separators, designed by engineers Jahn and Jahnke, accepted the water at about 110 degrees Celsius and 1.4 bar of pressure. The vertically mounted, tube shaped separators contained a centrifugal impeller at the top connected to an impeller-type scavenge pump at the bottom. The coolant was expanded through the upper impeller where it lost pressure, boiled and cooled. The by product was mostly very hot coolant and some steam. The liquid coolant was slung by the centrifugal impeller to the sides of the separator where it fell by gravity to the bottom of the unit. There, it was pumped to header tanks located in the leading edges of both wings by the scavenge pump. The presence of the scavenge pump was necessary to ensure the entire separator did not simply fill up with high pressure coolant coming from the engine.

Existing photographs of the engine bay of the final pre-production version of this system clearly show the liquid coolant from both separators was piped along the bottom left side of the engine compartment and into the right wing. The header tanks were located in the outer wing panels ahead of the main spar and immediately outboard of the main landing gear bays. The tanks extended over the same portion of the outer panel's span as the outer flaps. Coolant from the right wing header tank was pumped by a separate, electrical pump to the left wing header tank. Along the way from the right to left wing, the coolant passed through a conventional radiator mounted on the bottom of the fuselage. That radiator was retractable and intended for use only during ground running or slow speed flight. Nevertheless, coolant passed through it whenever the engine was running and regardless of whether it was extended or retracted. In the retracted position, the radiator offered little cooling, but some heat was exchanged into the aft fuselage. Finally, a return tube connected the left wing's header tank to that on the right. This allowed the coolant to equalize between the two header tanks and circulate through the retractable radiator. The engine drew coolant directly from both header tanks through two separate pipes that ran through the main landing gear bays, up the firewall at the back of the engine compartment and into the usual coolant intakes located at the top rear of the engine.

The steam collected in the separators was vented separately from the liquid coolant. The steam did not required mechanical pumping to do this, and the build up of pressure inside the separator was sufficient. The steam was piped down the lower right side of the engine bay and led into the open spaces between the upper and lower wing skins of the outer wing panels. There, it further expanded and condensed by cooling through the skins. The entire outer wing, both ahead of and behind the main spar, was used for this purpose covering that portion of the span containing the ailerons (the fuel was also carried entirely in the wings and occupied the areas behind the main spar in the center section and immediately ahead of the outboard flaps). The condensate was scavenged by electrically driven centrifugal pumps and fed to the header tanks. Sources indicate as many as 22 separate pumps were used for this, but it is not clear whether that number includes all of the pumps in the entire water and oil cooling systems or merely the number of pumps in the outer wing panels. The former is generally accepted.

Some sources state the outer wing panels used double skins top and bottom with the steam being ducted into a thin space between the outer and inner skins for cooling. A double skinned panel was used in the oil cooling system, but surviving photographs of the wings demonstrate they were conventionally single skinned, and the coolant was simply piped into the open spaces of the structure. Double skinning over such an extensive area would have made the aircraft unacceptably heavy. Furthermore, there was no access to the inner structure to repair damage, such as a bullet hole, from the inside as would be needed if the system used a double skin. A similar system was used by the earlier Supermarine Type 224. Contrary to assertions in some references, all of the He 100s that were built used the evaporative cooling system described above. A derivative of this system was also intended for a late war project based on the He 100, designated P.1076.

Unlike the cooling fluid, oil cannot be allowed to boil. This presented a particular problem with the Daimler-Benz DB 601 series of engines, because oil is sprayed against the bottom of the pistons resulting in a considerable amount of heat being transferred to the oil as opposed to the coolant. The He 100's oil cooling system was conceptually similar to the water cooling system in that vapor was generated using the heat of the oil and condensed back to liquid by surface cooling through the skins of the airframe. A heat exchanger was used to cool the oil by boiling ethyl alcohol. The oil itself was simply piped to and from this exchanger, which was apparently located in the aft fuselage. The alcohol vapor was piped into the fixed portions of the horizontal and vertical stabilizers and into a double skinned portion of the upper, aft fuselage behind the cockpit. This fuselage "turtle deck" panel was the only double skinned portion of the aircraft's cooling system. The use of a double skinned panel was possible here because the inside of panel was accessible in the event of repair. The retractable radiator below the fuselage was not used for the oil cooling system. Condensed alcohol was collected by a series of bellows pumps and returned to a single header tank that fed the heat exchanger. Some sources speculate that a small air intake located at the bottom front of the engine cowl was used for an auxiliary oil cooler. No such cooler was fitted, nor was there room for one at that point. This small inlet served simply to admit cool air into what was a very hot portion of the engine bay. Immediately above this vent were the two steam separators and immediately behind it were the hot coolant pipes coming from the separators.

Prototypes

V2 was completed in March, but instead of moving to Rechlin it was kept at the factory for an attempt on the 100 km closed circuit speed record. A course was marked out on the Baltic coast between Wustrow and M?ritz, 50 km apart, and the attempt was to be made at the aircraft's best altitude of 18,000 ft (5,500 m). After some time cleaning out the bugs the record attempt was set to be flown by Captain Herting, who had previously flown the aircraft several times.

At this point Ernst Udet showed up and asked to fly V2, after pointing out he had flown the V1 at Rechlin. He took over from Herting and flew the V2 to a new world 100 km closed circuit record on 5 June 1938, at 634.73 kph (394.6 mph). Several of the cooling pumps failed on this flight as well, but Udet wasn't sure what the lights meant and simply ignored them.

The record was heavily publicized, but in the press the aircraft was referred to as the "He 112U". Apparently the "U" stood for "Udet". At the time the 112 was still in production and looking for customers, so this was one way to boost sales of the older design. V2 was then moved to Rechlin for continued testing. Later in October the aircraft was damaged on landing when the tail wheel didn't extend, and it is unclear if the damage was repaired.

The V3 prototype received the clipped racing wings, which reduced span and area from 30 ft 10 in (9.4 m) and 155 ft? (14.4 m?), to 24 ft 11 in (7.6 m) and 118.4 ft? (11 m?). The canopy was replaced with a much smaller and more rounded version, and all of the bumps and joints were puttied over and sanded down. The aircraft was equipped with the 601M and flown at the factory.

In August the DB 601R engine arrived from Daimler-Benz and was installed. This version increased the maximum rpm from 2,200 to 3,000, and added methyl alcohol to the fuel mixture to improve cooling in the supercharger and thus increase boost. As a result the output was boosted to 1,776 hp (1,324 kW), although it required constant maintenance and the fuel had to be drained completely after every flight. The aircraft was then moved to Warnem?nde for the record attempt in September.

On one of the pre-record test flights by the Heinkel chief pilot, Gerhard Nitschke, the main gear failed to extend and ended up stuck half open. Since the aircraft could not be safely landed it was decided to have Nitschke bail out and let the aircraft crash in a safe spot on the airfield. Gerhard was injured when he hit the tail on the way out, and made no further record attempts.

V4 was to have been the only "production" prototype and was referred to as the "100B" model (V1 through V3 being "A" models). It was completed in the summer and delivered to Rechlin, so it wasn't available for modification into racing trim when V3 crashed. Although the aircraft was unarmed it was otherwise a service model with the 601M, and in testing over the summer it proved to be considerably faster than the Bf 109. At sea level the aircraft could reach 348 mph (560 kph), faster than the Bf 109E's speed at its best altitude. At 6,560 ft, it improved to 379 mph (610 kph), topping out at 416 mph (669 kph) at 16,400 ft before falling again to 398 mph (641 kph) at 26,250 ft. The aircraft had flown a number of times before its landing gear collapsed while standing on the pad on 22 October. The aircraft was later rebuilt and was flying by March 1939.

Although V4 was to have been the last of the prototypes in the original plans, production was allowed to continue with a new series of six aircraft. One of the airframes was selected to replace V3, and as luck would have it V8 was at the "right point" in its construction and was completed out of turn. It first flew on 1 December but this was with a standard DB 601Aa engine. The 601R was then put in the aircraft on 8 January 1939, and moved to a new course at Oranienberg. After several shakedown flights, Hans Dieterle flew to a new record on 30 March 1939, at 746.6 kph (463.9 mph). Once again the aircraft was referred to as the He 112U in the press. It is unclear when happened to V8 in the end; it may have been used for crash testing.

V5 was completed like V4, and first flew on 16 November. It was later used in a film about V8's record attempt, in order to protect the record breaking aircraft. At this point a number of changes were made to the design resulting in the "100C" model, and with the exception of V8 the rest of the prototypes were all delivered as the C standard.

V6 was first flown in February 1939, and after some test flights at the factory it was flown to Rechlin on 25 April. There it spent most of its time as an engine testbed. On 9 June the gear failed inflight, but the pilot managed to land the aircraft with little damage and it was returned to flying condition in six days.

V7 was completed on 24 May with a change to the oil cooling system. It was the first to be delivered with armament, consisting of two 20 mm MG/FF in the wings and four 7.92 mm MG17's arranged around the engine cowling. This made the 100 the most heavily armed fighter of its day. V7 was then flown to Rechlin where the armament was removed and the aircraft was used for a series of high speed test flights.

V9 was also completed and armed, but was used solely for crash testing and was "tested to destruction". V10 was originally to suffer a similar fate, but instead ended up being given the racing wings and canopy of the V8 and displayed in the German Museum in Munich as the record?setting "He 112U". It was later destroyed in a bombing attack.

Overheating problems and general failures with the cooling system motors continued to be a problem. Throughout the testing period failures of the pumps ended flights early, although some of the test pilots simply starting ignoring them. In March Kleinemeyer wrote a memo to Ernst Heinkel about the continuing problems, stating that Schw?rzler had asked to be put on the problem.

Another problem that was never cured during the prototype stage was a rash of landing gear problems. Although the wide-set gear should have eliminated the collapse of landing gears that plagued the Bf 109, especially in the difficult takeoffs and landings, the He 100's landing gear were not built to withstand heavy use and as a result they were no improvement over the Bf 109. V2, 3, 4 and 6 were all damaged to various degrees due to various gear failures, a full half of the prototypes.

Operational history

He 100D-0

Throughout the prototype period the various models were given series designations (as noted above), and presented to the RLM as the basis for series production. The Luftwaffe never took them up on the offer. Heinkel had decided to build a total of 25 of the aircraft one way or the other, so with ten down, there were another 15 of the latest model to go. In keeping with general practice, any series production is started with a limited run of "zero series" machines, and this resulted in the He 100D-0.

The D-0 was similar to the earlier C models, with a few notable changes. Primary among these was a larger vertical tail in order to finally solve the stability issues. In addition the cockpit and canopy were slightly redesigned, with the pilot sitting high in a large canopy with excellent vision in all directions. The armament was reduced from the C model to one 20 mm MG/FF-M in the engine V firing through the propeller spinner, and two 7.92 mm MG17s in the wings close to the fuselage.

The three D-0 aircraft were completed by the summer of 1939 and stayed at the Heinkel Marienehe plant for testing. They were later sold to the Japanese Imperial Navy to serve as pattern aircraft for a production line, and were shipped there in 1940. They received the designation AXHe.

He 100D-1

The final evolution of the short He 100 history is the D-1 model. As the name suggests the design was supposed to be very similar to the pre-production D-0s, the main planned change was to enlarge the horizontal stabilizer.

But the big change was the eventual abandonment of the surface cooling system, which proved to be too complex and failure prone. Instead an even larger version of the retractable radiator was installed, and this appeared to completely cure the problems. The radiator was inserted in a "plug" below the cockpit, and as a result the wings were widened slightly.

While the aircraft didn't match its design goal of 700 kph once it was loaded down with weapons, the larger canopy and the radiator, it was still capable of speeds in the 400 mph (644 kph) range. A low drag airframe is good for both speed and range, and as a result the He 100 had a combat radius between 900 and 1000 km compared to the Bf 109's 600 km. While not in the same league as the later escort fighters, this was at the time a superb range and may have offset the need for the Bf 110 to some degree. Finally, there were allegations that politics played a role in killing the He 100.

By this point the war was underway, and as the Luftwaffe would not purchase the aircraft in its current form, the production line was shut down.

The remaining 12 He 100D-1c fighters were used to form Heinkel's Marienehe factory defense unit, flown by factory test pilots. They replaced the earlier He 112s that were used for the same purpose, and the 112s were later sold off. At this early stage in the war there were no bombers venturing that far into Germany, and it appears that the unit never saw action. The eventual fate of the D-1s remains unknown. The aircraft were also put to an interesting propaganda/disinformation role, as the supposed Heinkel He 113.

Foreign use:

When the war opened in 1939 Heinkel was allowed to look for foreign licensees for the design. Japanese and Soviet delegations visited the Marienehe factory in late October, and were both impressed with what they saw. Thus it was in foreign hands that the 100 finally saw use, although only in terms of adopted design features. Six He 100s were exported to the Soviet Union and three were exported to Japan. Although any Japanese aircraft that survived the war would have been destroyed by the allies, there is a possibility that parts of or even a complete He 100 may exist somewhere in storage in Russia. It is also possible the Russians made plans or blueprints of their He 100s while the design was being studied.

The Soviets were particularly interested in the surface cooling system, and in order to gain experience with it they purchased the six surviving prototypes (V1, V2, V4, V5, V6 and V7). After arriving in the USSR they were passed onto the TsAGI institute for study; there they were analyzed with He 100 features influencing a number of Soviet designs, notably the LaGG-3 and MiG-1. Although the surface cooling system wasn't copied, the addition of larger Soviet engines made up for the difference and the LaGG-3 was a reasonably good performer. It's perhaps ironic that German aircraft would later be shot down by German inspired aircraft.

The Japanese were also looking for new designs, notably those using inline engines where they had little experience. They purchased the three D-0s for 1.2 million RM, as well as a license for production and a set of jigs for another 1.8 million RM. The three D-0s arrived in Japan in May 1940 and were re-assembled at Kasumigaura. They were then delivered to the Japanese Naval Air Force where they were re-named AXHei, for "Experimental Heinkel Fighter". When referring to the German design the aircraft is called both the He 100 and He 113, with at least one set of plans bearing the later name.

In tests the Navy was so impressed that they planned to put the aircraft into production as soon as possible as their land based interceptor; unlike every other armed forces organization in the world, the Army and Navy both fielded complete land based air forces. Hitachi won the contract for the aircraft and started construction of a factory in Chiba for its production. With the war in full swing in Europe however, the jigs and plans never arrived. Why this wasn't sorted out is something of a mystery, and it appears there isn't enough information in the common sources to say for sure what happened.

The DB 601 engine design was far more advanced than any indigenous Japanese design, which tended to concentrate on air cooled radials. To get a jump into the inline field, Kawasaki had already purchased the license for the 601A from Daimler Benz in 1938. The adoption process went smoothly, they adapted it to Japanese tooling and had it in production by late 1940 as the Ha-40.

At the same time Kawasaki was working on two parallel fighter efforts, the Ki-60 heavy fighter and the Ki-61. The former was abandoned after poor test results (the test pilots disliked the high wing loading) but work continued on the lightened Ki-61 with the Ha-40 engine. The Ki-61 was clearly influenced by the He 100.

Like the Ds, the Ki-61 lost the surface cooling system (although an early prototype may have included it), but is otherwise largely similar in design except for changes to the wing and vertical stabilizer. Since the Ki-61 was supposed to be lighter and offer better range than the Ki-60, the design had a longer and more tapered wing for better altitude performance. This also improved the handling and the aircraft was put into production. The Hien would prove to be the first of the Japanese aircraft that was truly equal to the contemporary US fighters.

World speed record

One aspect of the original Projekt 1035 was an intention to capture the absolute speed record for Heinkel and Germany. Both Messerschmitt and Heinkel vied for this record before the war. Messerschmitt ultimately won that battle with the first prototype of the Me-209, but the He 100 briefly held the record when Heinkel test pilot Hans Dieterle flew the eighth prototype to 746.606 kph on 30 March 1939. The third and eighth prototypes were specially modified for speed with unique outer wing panels of reduced span. The third prototype crashed during testing. The record flight was made using a special version of the DB-601 engine that offered 2,700 hp and had a service life of just 30 minutes. Prior to setting this absolute speed record over a short, measured course, Ernst Udet flew the second prototype to a 100 km closed course record of 634.32 kph on 5 June 1938. Udet's record was apparently set using a standard DB 601a engine.

There is a debate regarding the correct designation of the He 100 aircraft actually built. One group holds that all of the machines were either "Versuchs" or "trials" prototypes and pre-production "A-0" series machines. This is consistent with the RLM's normal practice of changing an aircraft's sub-designation only with a significant redesign, such as an engine change. All of the He 100s built were essentially the same, and even the prototypes were later updated to the production standard before they were exported to the Soviet Union. The second group holds that the Heinkel factory intended "A," "B," "C" and "D" series aircraft, and the final version was the "D." This camp also holds that there were separate "D-0" and "D-1" production runs, although in extremely limited numbers. Most literature follows the latter school of thought, Since the He 100 was never accepted for operational use by the Luftwaffe, it is unlikely there was ever an official resolution of this issue. The separate letter designations "A" through "D" appear to have come from internal Heinkel documents.

Further developments

In late 1944 the RLM went to manufacturers for a new high altitude fighter with excellent performance - the Ta 152H (a version of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190) was currently in limited production for just this task but Heinkel was contracted to design an aircraft, and Siegfried G?nter was placed in charge of the new Projekt 1076.

The resulting design was similar to the He 100, but the many detail changes resulted in an aircraft that looked all new. It sported a new and longer wing for high altitude work, which lost the gull wing bend and was swept forward slightly at eight degrees. Flaps or ailerons spanned the entire trailing edge of the wing giving it a rather modern appearance. The cockpit was pressurized for high altitude flying, and covered with a small bubble canopy that was hinged to the side instead of sliding to the rear. Other changes that seem odd in retrospect is that the gear now retracted outward like the original Bf 109, and the surface cooling system was re-introduced. Planned armament was one 30 mm MK 103 cannon firing through the propeller hub, and two wing mounted 30 mm MK 108 cannons.

The use of one of three different engines was planned: the DB 603M with 1,825 hp (1,361 kW), the DB 603N with 2,750 hp (2,051 kW) or the Jumo 213E with 1,750 hp (1,305 kW). The 603M and 213E both supplied 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) using MW-50 water injection. Performance with the 603N was projected to be 880 kph (546 mph), which would have stood as a record for many years even when faced with dedicated racing machines. Performance would still be excellent even with the far more likely 2,000 hp (1.5 MW) class engines, the 603M was projected to give it the high speed of 855 kph (532 mph).

These figures are somewhat suspect though, and are likely just optimistic guesses that could not have been met ? something Heinkel was famous for. Propellers lose efficiency as they approach the speed of sound, and eventually they no longer provide an increase in thrust for an increase in engine power. Even the advanced counter rotating VDM design is unlikely to have been able to effect this problem too much.

The design apparently received low priority, and it was not completed by the end of the war. Siegfried G?nter later completed the detailed drawings and plans for the Americans in mid-1945.

Legacy

In 1939, it was reputedly one of the most advanced fighter designs, even faster than the later Fw 190, with performance unrivalled until the introduction of the Vought F4U Corsair in 1943. Nevertheless the aircraft was not ordered into production. The reasons the He 100 wasn't put into service seems to vary depending on the person telling the story, and picking any one version results in a firestorm of protest.

Some say it was politics that killed the He 100. However this seems to stem primarily from Heinkel's own telling of the story, which in turn seems to be based on some general malaise over the He 112 debacle. The fact is that Heinkel was well respected within the establishment regardless of Messerschmitt's success with the Bf 109 and Bf 110, and this argument seems particularly weak.

Others blame the bizarre production line philosophy of the RLM, which valued huge numbers of single designs over a mix of different aircraft. This too seems somewhat suspect considering that the Fw 190 was purchased shortly after this story ends.

For these reasons it seems safe to accept the RLM version of the story largely at face value; that the production problems with the DB series of engines was so acute that all other designs based on the engine were canceled. At the time the DB 601 engines were being used in both the Bf 109 and Bf 110 aircraft, and Daimler couldn't keep up with those demands alone. The RLM eventually forbade anyone but Messerschmitt from receiving any DB 601s, leading to the shelving of many designs from a number of vendors. Furthermore, the Bf 109 and Bf 110 were perceived as superior to their likely opponents, which made the requirement for an even more powerful aircraft less imperative.

The only option open to Heinkel was a switch to another engine, and the RLM expressed some interest in purchasing such a version of the He 100. At the time the only other useful inline was the Junkers Jumo 211, and even that was in short supply. However the design of the He 100 made adaptation to the 211 difficult; both the cooling system and the engine mounts were designed for the 601, and a switch to the 211 would have required a redesign. Heinkel felt it wasn't worth the effort considering the aircraft would end up with inferior performance, and so the He 100 production ends on that sour note.

For this reason more than any other the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 became the next great aircraft of the Luftwaffe, as it was based around the otherwise unused Bramo 139 (and later BMW 801) radial engine. Although production of these engines was only starting, the lines for the airframes and aircraft could be geared up in parallel without interrupting production of any existing design, which was exactly what happened.

Sources:

Gunston, Bill & Wood, Tony - Hitler's Luftwaffe, 1977, Salamander Books Ltd., London

Wikipedia - He 100

Specifications

Origin: Ernst Heinkel AG

Models: He 100 V1 to V8 and He 100D-1

Type: Single-seat fighter

First Flight: Jan. 22, 1938

Number produced: 25

ENGINE:

Model: Daimler-Benz DB 601 Aa

Type: Inverted-vee-12 liquid-cooled

Number: One Horsepower: 1,175 hp

DIMENSIONS:

Span: 30 ft. 10? in. (9.41m)

Length: 26 ft. 10? in. (8.195m)

Height: 11 ft. 9? in. (3.60m)

Wing area: 156 sq. ft (14.5 sq. m)

WEIGHTS:

Empty: 1810kg (3,990 lbs.)

Maximum Loaded: 2500kg (5,512 lbs.)

PERFORMANCE:

Maximum speed: 670kph (416mph)

Service Ceiling: 11,000m (36,090ft)

Range: 900km (559 Miles)

ARMAMENT:

He 100D-0: Two MG 17 and a 20mm MG/FF

He 100D-1: N/A

Regards Duggy -

Main Admin

Main Admin

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources