Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- RAF Library

- Westland Whirlwind (fighter)

Westland Whirlwind (fighter)

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

9 years agoFri Feb 07 2025, 10:20pmDuggy

Main AdminDesign and development

Main AdminDesign and development

By the mid-1930s, aircraft designers around the world perceived that increased attack speeds were imposing shorter firing times on fighter pilots. This implied less ammunition hitting the target, so something would have to be done to offset this effect and ensure the aircraft could destroy its target. Instead of two rifle-calibre machine guns, six or eight were required; studies had shown that eight machine guns could deliver 256 rounds per second. Cannon, such as the French 20mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404, which could fire explosive ammunition, offered another type of heavy firepower and attention turned to aircraft designs which could carry four cannon. While the most agile fighter aircraft were generally small and light, their limited fuel storage also limited their range and tended to restrict them to defensive and interception roles. The larger airframes and bigger fuel loads of twin-engined designs were therefore favoured for long-range, offensive roles.

The first British specification for a high performance machine-gun monoplane was F.5/34, but the aircraft produced were overtaken by developments by Hawker and Supermarine. The RAF Air Staff thought that an experimental aircraft armed with the 20mm cannon was needed urgently and Air Ministry specification F.37/35 was issued in 1935. The specification called for a single-seat day and night fighter armed with four cannon. The top speed had to be at least 40 mph (64 km/h) greater than that of contemporary bombers ? at least 330 mph (530 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,570 m).

Eight aircraft designs from five companies were submitted in response to the specification. Boulton Paul offered the P.88A and P.88B (two related single engine designs); Bristol the single-engined Type 153 and the twin-engined Type 153A; Hawker offered a variant of the Hurricane; the Supermarine 312 was a variant of Spitfire and the Supermarine 313 a twin engined design with four guns in the nose and potentially a further two firing through the propeller hubs; the Westland P.9 had two Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26 engines and a twin tail.

When the designs were considered in May 1936, there were two issues ? concern that two engines would be less manoeuvrable than a single-engined design and that uneven recoil from cannon set in the wings would give less accurate fire. The conference favoured two engines with the cannon set in the nose and recommended the Supermarine 313.

Although Supermarine's efforts were favoured due to their previous success with fast aircraft and the promise of the Spitfire which was undergoing trials, neither they nor Hawker were in a position to deliver a modified version of their single-engined designs quickly enough. Westland, which had less work and was further advanced in their project, was chosen along with the P.88 and the Type 313 for construction. A contract for two P.9s was placed in February 1937 which were expected to be flying in mid-1938. The P.88s were ordered in December along with a Supermarine design to F37/35 but both were cancelled in January.

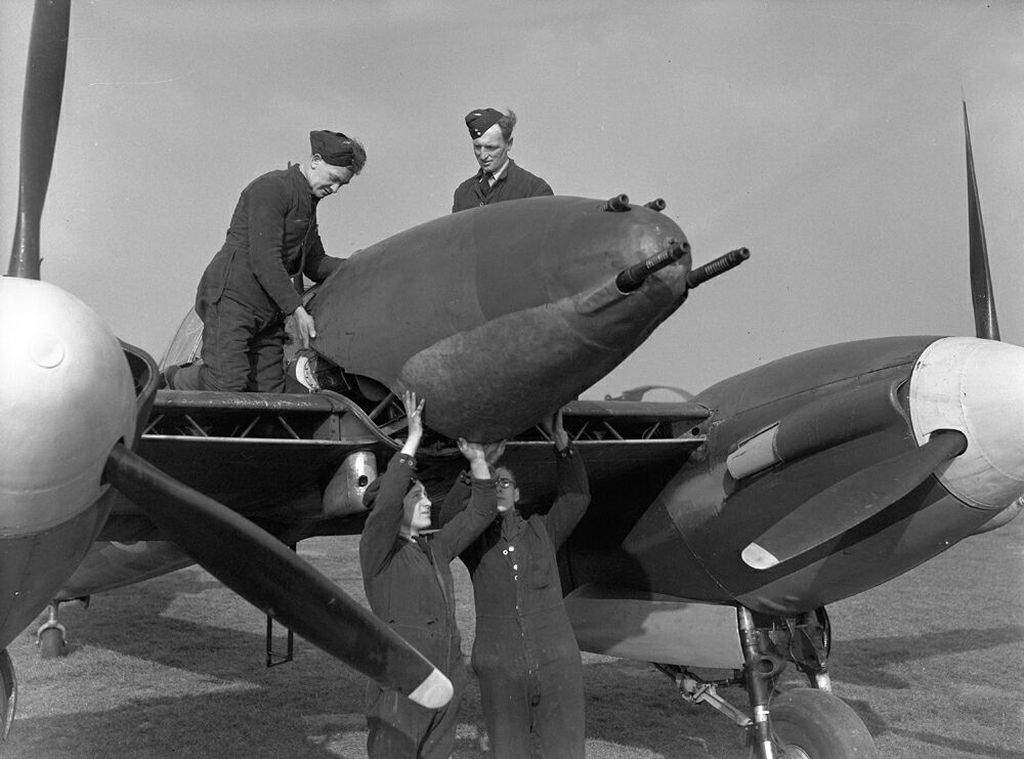

Westland's design team, under the new leadership of Teddy Petter (who later designed the English Electric Canberra, Lightning and Folland Gnat) designed an aircraft that employed state-of-the-art technology. The magnesium monocoque fuselage was a small tube with a T-tail at the end, although as originally conceived, the design featured a twin tail which was discarded when large Fowler flaps were added that caused large areas of turbulence over the tail unit. The horizontal stabilizer (tailplane) was moved up out of the way of the disturbed air flow caused when the flaps were down. The engines were the Kestrel K.26, later renamed Peregrine, with internal exhaust and leading edge radiators to reduce drag. The airframe was built completely of stressed-skin duraluminium, with the pilot sitting high under one of the world's first full bubble canopies, while the low and forward location of the wing made for superb visibility (except for directly over the nose). Four 20 mm cannon were mounted in the nose; the 600 lb/minute fire rate made it the most heavily armed fighter aircraft of its era. The clustering of the weapons also meant that there were no convergence problems as with wing-mounted guns. Hopes were so high for the design that it remained "top secret" for much of its development, although it had already been mentioned in the French press.

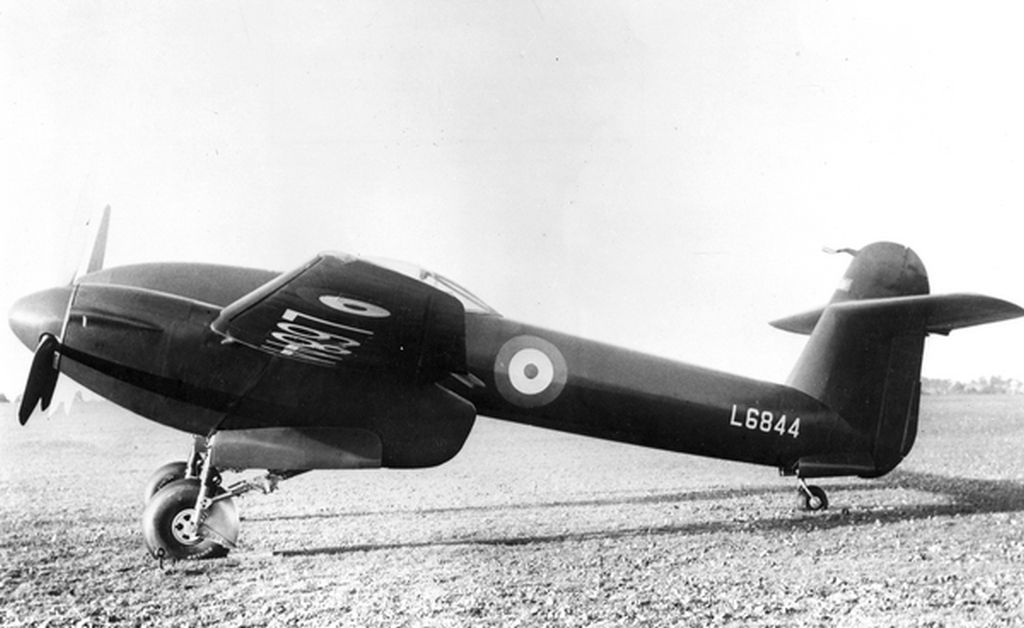

The first prototype (L6844) flew on 11 October 1938, construction had been delayed chiefly due to the new features and also the late delivery of the engines. It was passed to RAE Farnborough at the end of the year. Further service trials were carried out at Martlesham Heath. It exhibited excellent handling and was very easy to fly at all speeds. The only exception was the inadequate directional control during takeoff which necessitated an increased rudder area above the tailplane.

Below 2nd prototype

The Whirlwind was quite small, only slightly larger than the Hurricane in overall size, but smaller in terms of frontal area. The landing gear was fully retractable and the entire aircraft was very "clean" with few openings or protuberances. Radiators were in the leading edge on the inner wings rather than below the engines. This careful attention to streamlining and two 885 hp Peregrine engines powered it to over 360 mph (580 km/h), the same speed as the latest single-engine fighters.

But there were problems as well. The aircraft had limited range, under 300 miles combat radius, which made it marginal as an escort. the first deliveries of Peregrine engines did not reach Westland until January 1940.

By late 1940, the Supermarine Spitfire was scheduled to mount 20 mm cannon so the "cannon-armed" requirement was being met. In addition, by this time the role of escort fighter was becoming less important as RAF Bomber Command turned to night bomber missions. The main qualities the RAF were looking for in a twin-engine fighter were range and carrying capacity (to allow the large radar apparatus of the time to be carried), in which requirements the Bristol Beaufighter could perform just as well as or even better than the Whirlwind.

Production orders were contingent on the success of the test program; delays caused by over 250 modifications to the two prototypes led to an initial production order for 200 aircraft being held up until January 1939 followed by a second order for a similar number, deliveries to fighter squadrons being scheduled to begin in September 1940. Earlier, due to the lower expected production at Westland, there had been suggestions that production should be by other firms and an early 1939 plan to build 600 of them at the Castle Bromwich factory was dropped in favour of Spitfire production.

However, in spite of the Whirlwind's initial promise, production ended in January 1942, after the completion of just 2 prototypes and 112 production aircraft. A primary reason for the limited production, was the need for Rolls-Royce to concentrate on the development and production of the Merlin, and the troubled Vulture, rather than the Peregrine engine. Westland were aware that their design ? which had been built around the Peregrine ? was incapable of using anything larger without extensive redesigning. After the cancellation of the Whirlwind, Petter campaigned for the development of a Whirlwind Mk II, which was to have been powered by an improved 1,010 hp Peregrine which was to use 100 Octane fuel and an improved, higher altitude rated supercharger. This proposal was aborted owing to Rolls-Royce's cancellation of further development of the engine. In addition to the limitations of the Peregrine, it was shown that building a Whirlwind consumed three times as much alloy as a Spitfire.

Operational history

Many pilots who flew the Whirlwind praised its performance. Sergeant G. L. Buckwell of 263 Squadron, who was shot down in a Whirlwind over Cherbourg, later commented that the Whirlwind was "great to fly ? we were a privileged few... In retrospect the lesson of the Whirlwind is clear... A radical aircraft requires either prolonged development or widespread service to exploit its concept and eliminate its weaknesses. Too often in World War II, such aircraft suffered accelerated development or limited service, with the result that teething difficulties came to be regarded as permanent limitations." Bruce Robertson, in The Westland Whirlwind Described, quotes a 263 Squadron pilot as saying, "It was regarded with absolute confidence and affection."

An aspect of the type often criticised was the high landing speeds imposed by the wing design. Because of the low production level, based on the number of Peregrines available, no redesign of the wing was contemplated, although Westland did test the effectiveness of leading-edge slats to reduce speeds. When the slats were activated with such force that they were ripped off the wings, the slats were wired shut.

As the performance of the Peregrine engines fell off at altitude, the Whirlwind was most often used in ground attack missions over France, attacking German airfields, marshaling yards, and railway traffic. The Whirlwind was used to particularly good effect as a gun platform for destroying locomotives. Some pilots were credited with several trains damaged or destroyed in a single mission. The aircraft was also successful in hunting and destroying German E-boats which operated in the English Channel. At lower altitudes, it could hold its own against the Bf 109. Though the Peregrine was a much-maligned powerplant, it actually proved to be more reliable than the troublesome Napier Sabre engine used in the Hawker Typhoon, the Whirlwind's successor. The Whirlwind's twin engines meant that seriously damaged aircraft were able to return from dangerous bombing missions over occupied France and Belgium with one engine knocked out. The placement of the wings and engines ahead of the cockpit allowed the aircraft to absorb a great deal of damage, while the cockpit area remained largely intact. The rugged frame of the Whirlwind gave pilots greater protection than contemporary aircraft during crash landings and ground accidents.

Philip J. R. Moyes noted in Aircraft in Profile 191: The Westland Whirlwind:

The basic feature of the Whirlwind was its concentration of firepower: its four closely-grouped heavy cannon in the nose had a rate of fire of 600 lb./minute ? which, until the introduction of the Beaufighter, placed it ahead of any fighter in the world. Hand in hand with this dense firepower went a first-rate speed and climb performance, excellent manoeuvrability, and a fighting view hitherto unsurpassed. The Whirlwind was, in its day, faster than the Spitfire down low and, with lighter lateral control, was considered to be one of the nicest "twins" ever built? From the flying viewpoint, the Whirlwind was considered magnificent.

The first squadron to receive the Whirlwind was No. 25 Squadron, then based at North Weald. The squadron was fully equipped with radar-equipped Bristol Blenheim IF night fighters when Squadron Leader K. A. K. MacEwen flew prototype Whirlwind L6845 from Boscombe Down to North Weald on 30 May 1940. The following day it was flown and inspected by four of the squadron's pilots, and the next day was inspected by the Secretary of State for Air, Sir Archibald Sinclair, and Lord Trenchard. The first two production Whirlwinds were delivered in June to 25 Squadron for night-flying trials. It was then decided, however, to re-equip No. 25 Squadron with the two-seat Bristol Beaufighter night fighter, as it was already an operational night fighter squadron.

It was instead decided that the first Whirlwind squadron would be 263 Squadron, which was reforming at Grangemouth, Scotland after disastrous losses in the Norwegian Campaign. The first production Whirlwind was delivered to No. 263 Squadron by its commander, Squadron Leader H. Eeles on 6 July. Deliveries were slow, with only five on strength with 263 Squadron on 17 August 1940, with none serviceable. (The squadron supplemented its strength with Hawker Hurricanes to allow the squadron's pilots to fly in the meantime. Despite the Battle of Britain and the consequent urgent need for fighters, 263 Squadron remained in Scotland - Air Chief Marshall Hugh Dowding, in charge of RAF Fighter Command, stated on 17 October that 263 could not be deployed to the south because "there was no room for 'passengers' in that part of the world".

The first Whirlwind was written off on 7 August when Pilot Officer McDermott had a tyre blow out while taking off in P6966. In spite of this he managed to get the aircraft airborne. Flying Control advised him of the dangerous condition of his undercarriage, and to land the aircraft in such condition was extremely hazardous. PO McDermott bailed out of the aircraft between Grangemouth and Stirling. The aircraft dived in and buried itself 30 feet into the ground. On recent inspection of the salvaged wreck of P6966, it was noticed that the defective tyre fitted was not of the correct size for a Whirlwind. Instead, it was the correct size for a Hawker Hurricane which 263 Squadron was also flying at that time.

No. 263 Squadron moved south to RAF Exeter and was declared operational with the Whirlwind on 7 December 1940. Initial operations consisted of convoy patrols and anti E-boat missions. The Whirlwind?s first confirmed kill occurred on 8 February 1941, when an Arado Ar 196 floatplane was shot down; the Whirlwind responsible also crashed into the sea and the pilot was killed. From then on the squadron was to have considerable success with the Whirlwind while flying against enemy Junkers Ju 88s, Dornier Do 217s, Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s.

263 Squadron also occasionally carried out day bomber escort missions with the Whirlwinds. One example was when they formed part of the escort of 54 Blenheims on a low-level raid against power stations near Cologne on 12 August 1941; owing to the relatively short range of the escorts, including the Whirlwinds, the fighters turned back near Antwerp, with the bombers continuing on without escort. Ten Blenheims were lost.

The major role for the squadron's Whirlwinds, however, became low-level attack, flying cross-channel "Rhubarb" sweeps against ground targets and "Roadstead" attacks against shipping. The Whirlwind proved a match for German fighters at low level, as demonstrated on 6 August 1941, when four Whirlwinds on an anti-shipping strike were intercepted by a large formation of Messerschmitt Bf 109s, and claimed three Bf 109s destroyed for no losses. A second Whirlwind squadron, No. 137, formed in September 1941, specialising in attacks against railway targets. In the summer of 1942, both squadrons' Whirlwinds were fitted with racks to carry two 250 lb or 500 lb bombs, and nicknamed Whirlibombers. These undertook low-level cross-channel "Rhubarb" sweeps, attacking locomotives, bridges, shipping and other targets.

No. 137 Squadron's worst losses were to be on 12 February 1942 during the Channel Dash, when they were sent to escort five British destroyers, unaware of the escaping German warships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Four Whirlwinds took off at 13:10 hours, and soon sighted warships through the clouds about 20 miles from the Belgian coast. They descended to investigate and were immediately jumped by about 20 Bf 109s of Jagdgeschwader 2. The Whirlwinds shot at anything they got in their sights, but the battle was against odds. While this was going on, at 13:40 two additional Whirlwinds were sent up to relieve the first four, and two more Whirlwinds took off at 14:25. Four of the eight Whirlwinds failed to return.

From 24 October until 26 November 1943, Whirlwinds of 263 Squadron made several large attacks against the German blockade runner M?nsterland, in dry dock at Cherbourg. As many as 12 Whirlwinds participated at a time in dive bombing attacks carried out from 12,000 to 5,000 ft using 250 lb bombs. The attacks were met by very heavy anti-aircraft fire, but virtually all bombs fell within 500 yards of the target. Only one Whirlwind was lost during the attacks.

The last Whirlwind mission to be flown by 137 Squadron occurred on 21 June 1943, when five Whirlwinds took off on a "Rhubarb" attack against the German airfield at Poix. One (P6993) was unable to locate the target and instead bombed a supply train north of Rue. While returning, the starboard throttle jammed in the fully open position and the engine eventually lost power. It made a forced landing in a field next to RAF Manston, but the aircraft was a complete write-off, although, as in many other crash landings in the type, the pilot walked away unhurt.

No. 263 Squadron, the first and last squadron to operate the Whirlwind, flew its last Whirlwind mission on 29 November 1943, turning in their aeroplanes and converting to the Hawker Typhoon in December that year. On 1 January 1944, the type was officially declared obsolescent. The remaining serviceable aircraft were transferred to No. 18 Maintenance Unit, while those undergoing repairs or overhaul were only allowed to be repaired if they were in near-flyable condition. An official letter forbade aircraft needing repair to be worked on.

P6969 'HE-V' of 263 in flight over the West Country

The aircraft was summed up by Francis K. Mason?s comments in Royal Air Force Fighters of World War Two, Vol. One:

Bearing in mind the relatively small number of Whirlwinds that reached the RAF, the type remained in combat service, virtually unmodified, for a remarkably long time?The Whirlwind, once mastered, certainly shouldered extensive responsibilities and the two squadrons were called upon to attack enemy targets from one end of the Channel to the other, by day and night, moving from airfield to airfield within southern England.

Below company demonstrator

General characteristics

Crew: One pilot

Length: 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m)

Wingspan: 45 ft 0 in (13.72 m)

Height: 11 ft 0 in (3.35 m)

Wing area: 250 ft? (23.2 m?)

Airfoil: NACA 23017-08

Empty weight: 8,310 lb (3,777 kg)

Loaded weight: 10,356 lb (4,707 kg)

Max. takeoff weight: 11,445 lb (5,202 kg)

Powerplant: 2 ? Rolls-Royce Peregrine I liquid-cooled V12 engine, 885 hp (660 kW) at 10,000 ft (3,050 m) with 100 octane fuel each

Propellers: de Havilland constant speed propeller

Propeller diameter: 10 ft (3.28 m)

Performance

Maximum speed: 360 mph (313 knots, 580 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,570 m)

Stall speed: 95 mph (83 knots, 153 km/h) (flaps down)

Range: 800 mi[44] (696 nmi, 1,288 km)

Combat radius: 150 mi (130 nmi, 240 km) as low altitude fighter, with normal reserves[29]

Service ceiling: 30,300 ft (9,240 m)

Armament

Guns: 4x Hispano 20 mm cannon with 60 rounds per gun

Bombs: 2x 250 lb (115 kg) or 500 lb (230 kg) bombs

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources