Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- RAF Library

- Stirling Stuff

Stirling Stuff

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

13 years agoFri Nov 03 2023, 04:33pmDuggy

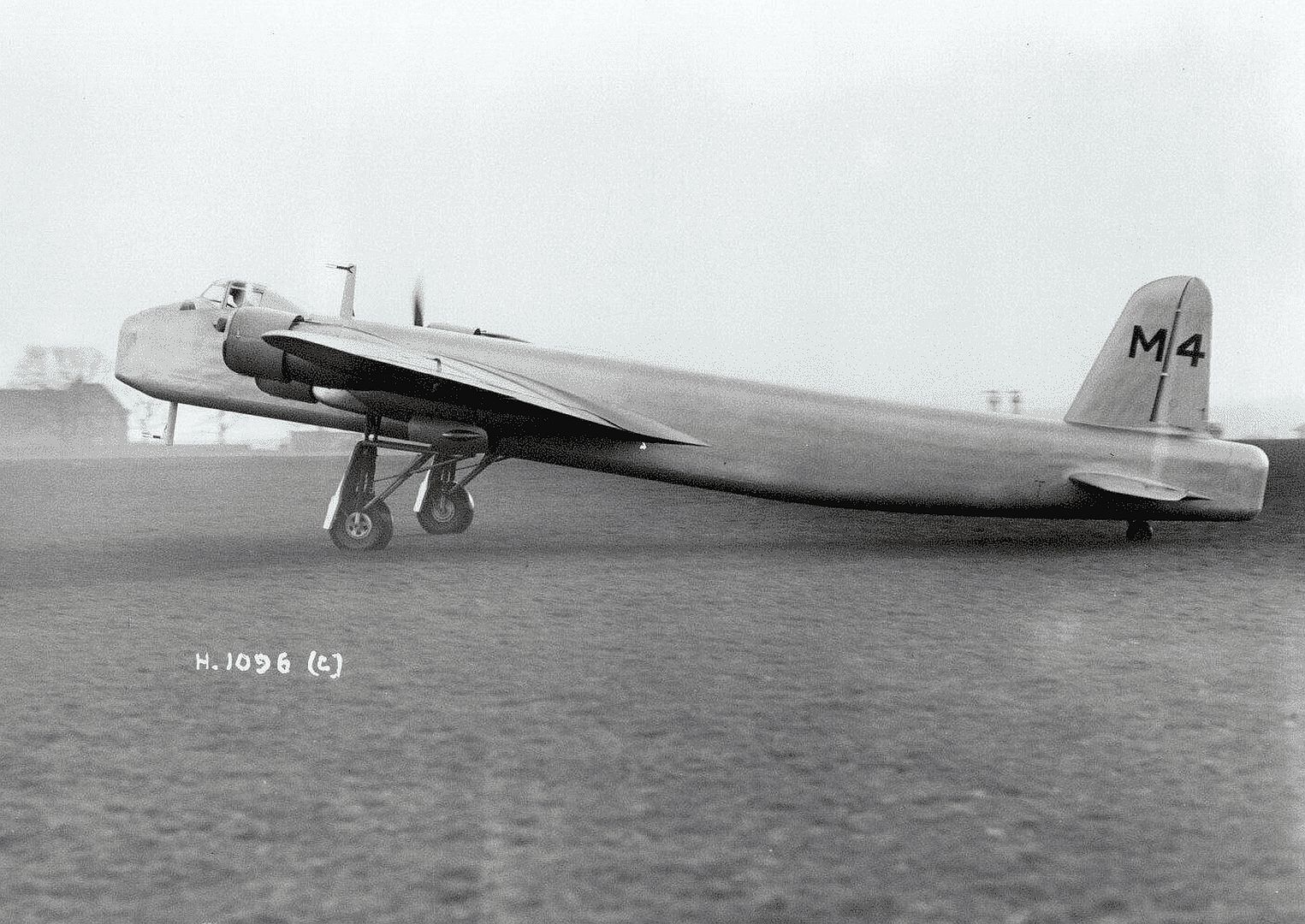

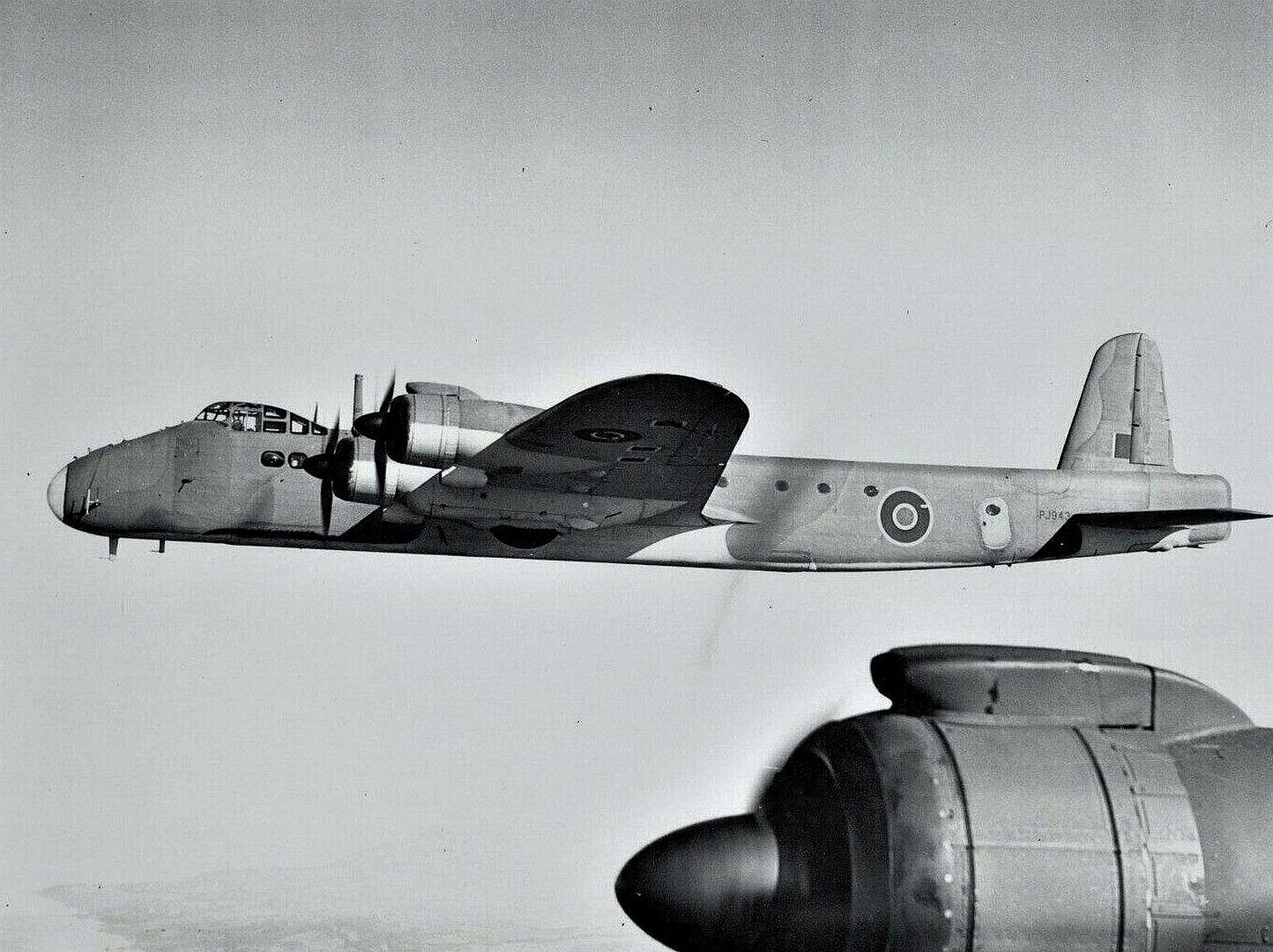

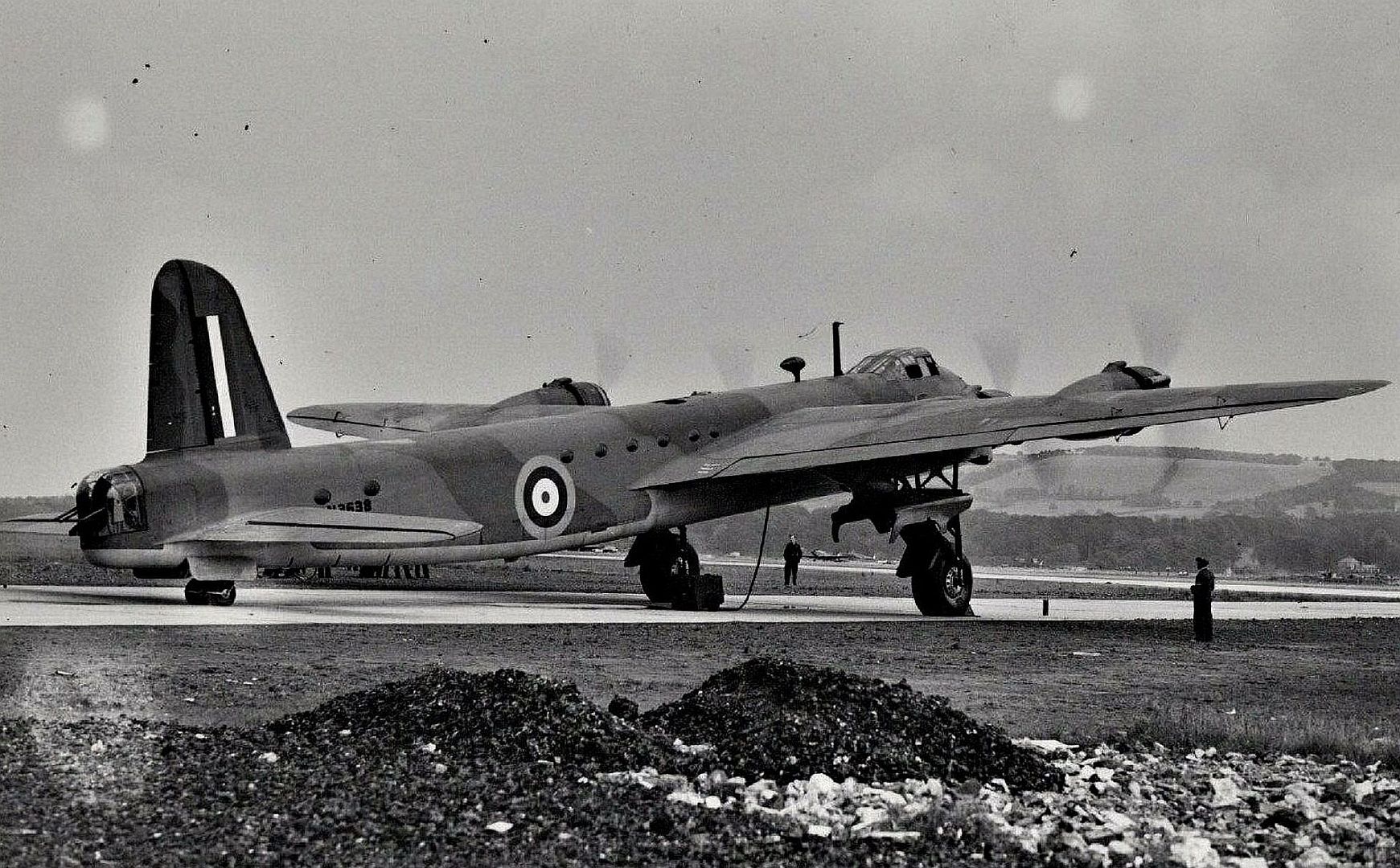

Main AdminThe first of many was ---- "The single Short S.31 Stirling prototype, coded M4, flies over the River Medway on a test flight out of Rochester. It was powered by four Pobjoy Niagara engines and was a half scale, aerodynamic tests version of the future proposed Stirling bomber.

Main AdminThe first of many was ---- "The single Short S.31 Stirling prototype, coded M4, flies over the River Medway on a test flight out of Rochester. It was powered by four Pobjoy Niagara engines and was a half scale, aerodynamic tests version of the future proposed Stirling bomber.

And below the S.31 at Rochester Airport 24-11-1938.

And here's a link to probably the most enthusiastic restoration in the world at the moment.

http://www.stirlingproject.co.uk/

World War II's first four-engined bomber: the heavy-weight which spear-headed the RAF.s attacks on German targets.

>This bloody contraption will never fly" commented Fight Engineer Albert Swales, RAF, as he stepped into his first Stirling bomber, a plane developed and tested over a few short months, during a period of prewar tension and economy. The Stirling did fly, but its progress was impeded by a government which constantly changed its mind over production requirements,even interfering with the design. At the end of the war, representatives of that same government concluded that the Stirling had been a disappointment. Some of the crews who fought in it and lived against all the fortunes of war declared that it was an aircraft of the highest caliber. This, then, was the paradox of the Short Bros. four engined Stirling heavy bomber. All things to all men! A magnificently conceived flying and fighting machine weighing 30 tons with 60,000 parts, but put together by semi-skilled builders, and watered down by bureaucracy and circumstance.

The Stirling came into being when the Air Ministry of 1936 accepted the Short company's design for an aircraft to meet their specification 812/36. This new machine was intended to meet the threat of the Luftwaffe. Germany was building to unprecedented peacetime strength and arrogantly crowing the noises of war. 812/36 demanded a plane of exceptional qualities.

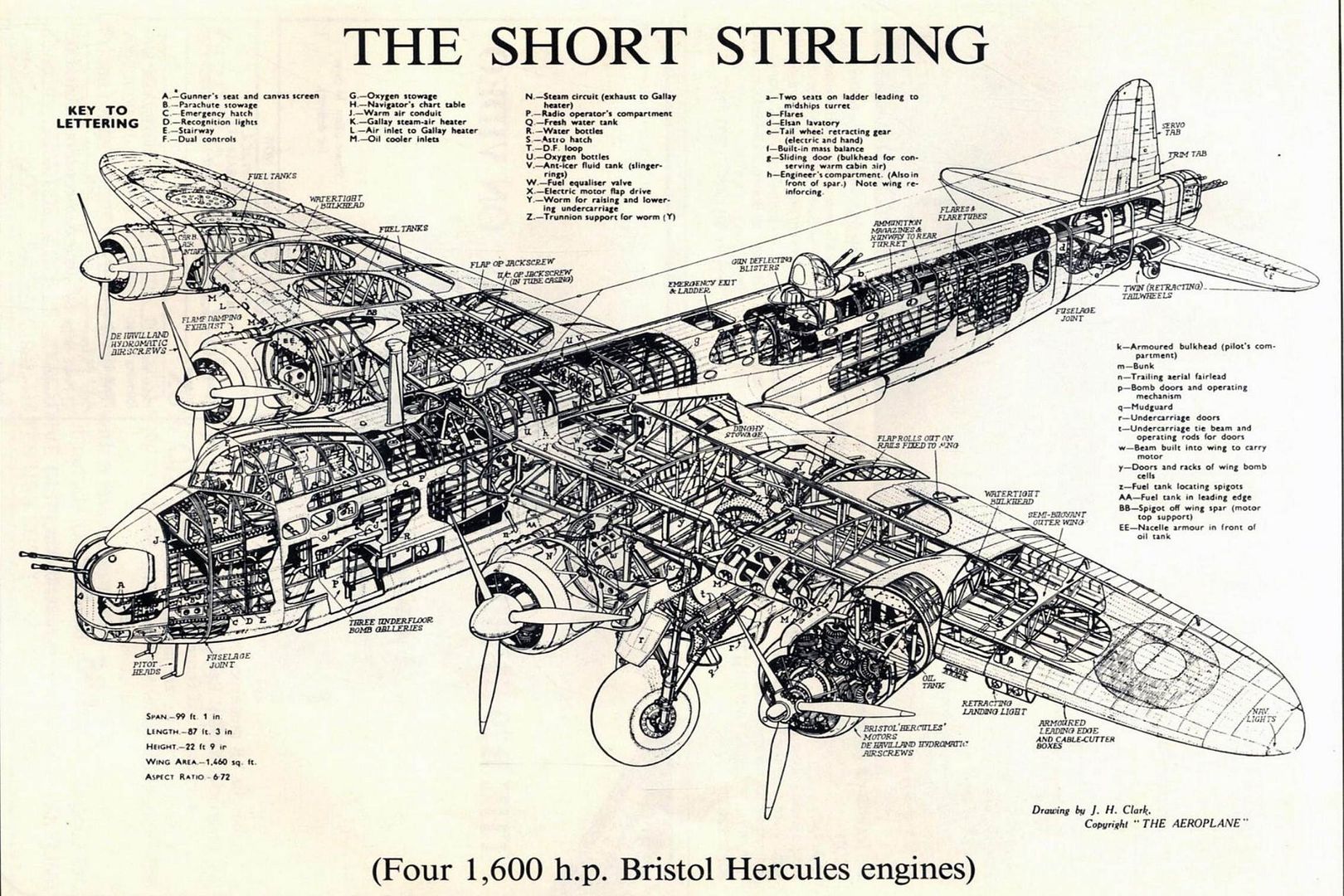

The Stirling was the first purpose designed four engined bomber since 1916. It was required to carry a crew of six and a pay load of up to 14,000lb of bombs, giving a normal all-up weight of 48,000lb, with an envisaged maximum overload weight of 65,000lb. (Unfortunately the largest bomb the Stirling was able to carry was the 2,000lb AP, due to the 42ft long bomb bay being divided into smaller sections.) It had to have a cruising speed in excess of 200mph and to be capable of reaching Berlin. To cope with existing airfields it had to be able to clear a 50ft obstacle at 1,400 yards. From this specification it is apparent that Short's answer to Churchill's request for a bomber able to deliver "the shattering strokes of retributive justice" had to be a compromise: an amalgum of many tried and tested techniques. From this stemmed all the Stirling's short comings as well as its many virtues.

The first of the virtues became apparent as early as October 1938. John Lankester Parker, Short's chief test pilot, was proving the design, which had been built of wood to exactly half the scale of the specification. Engines on the half size model were four 90hp Pobjoy Niagara III seven-cylinder radials. At a distance, S31 had the same perspective as a full sized bomber. Secrecy at the trials was so successful that RAF fighter pilots, trying to close with the aircraft to identify an unidentified four engined machine, were astonished to discover that it could outrun them.

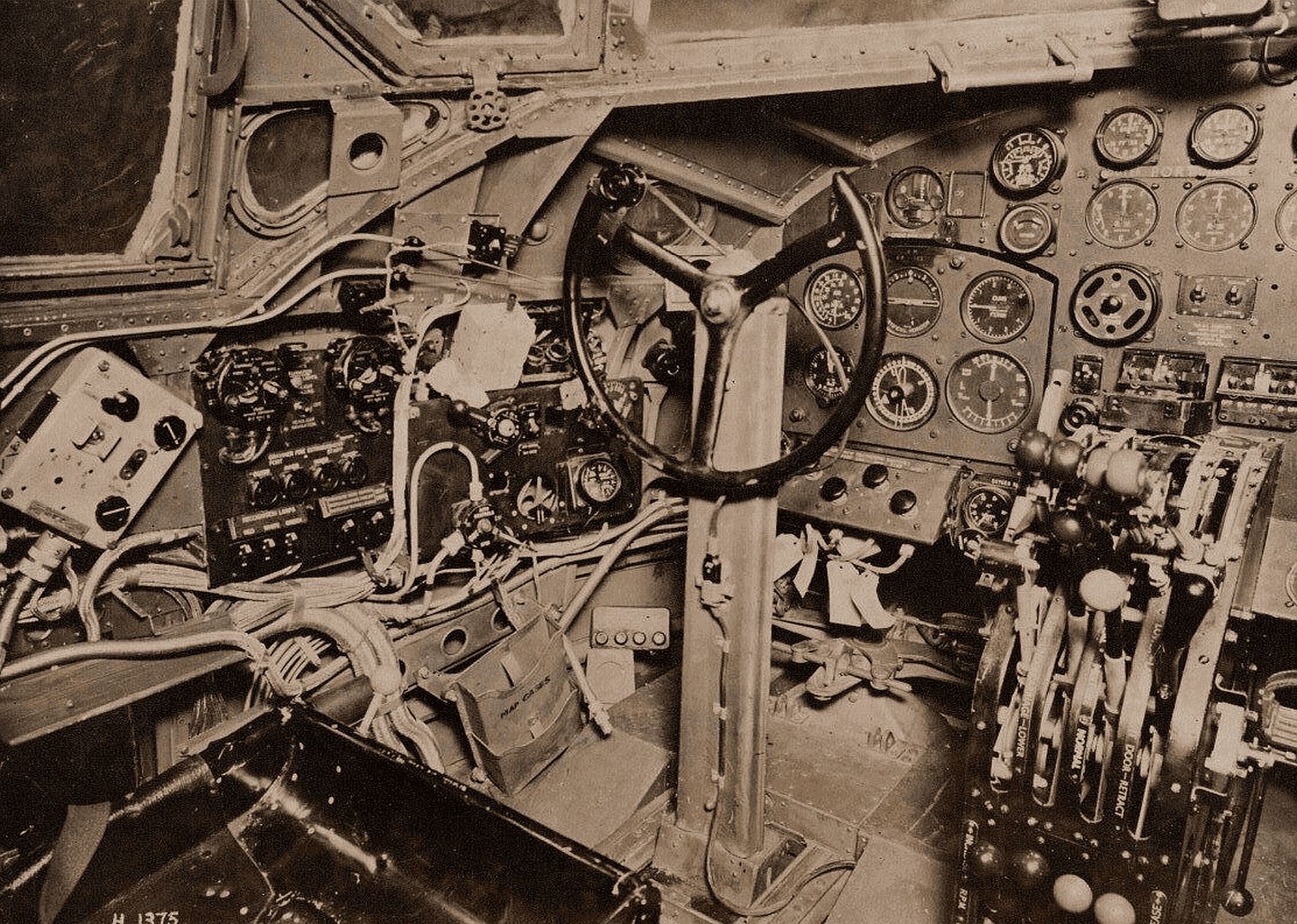

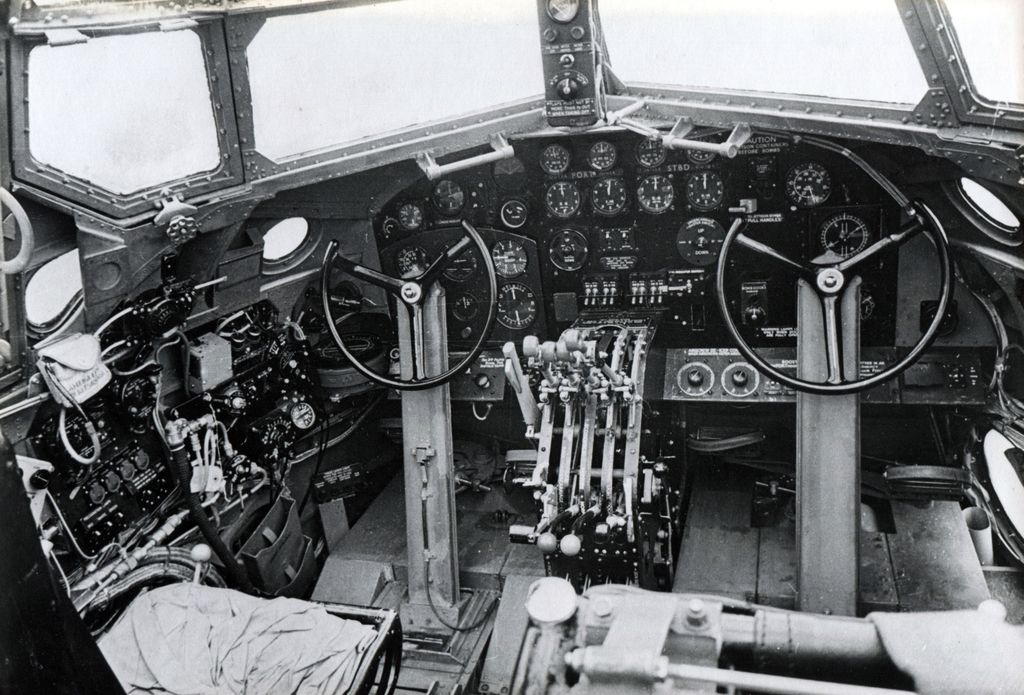

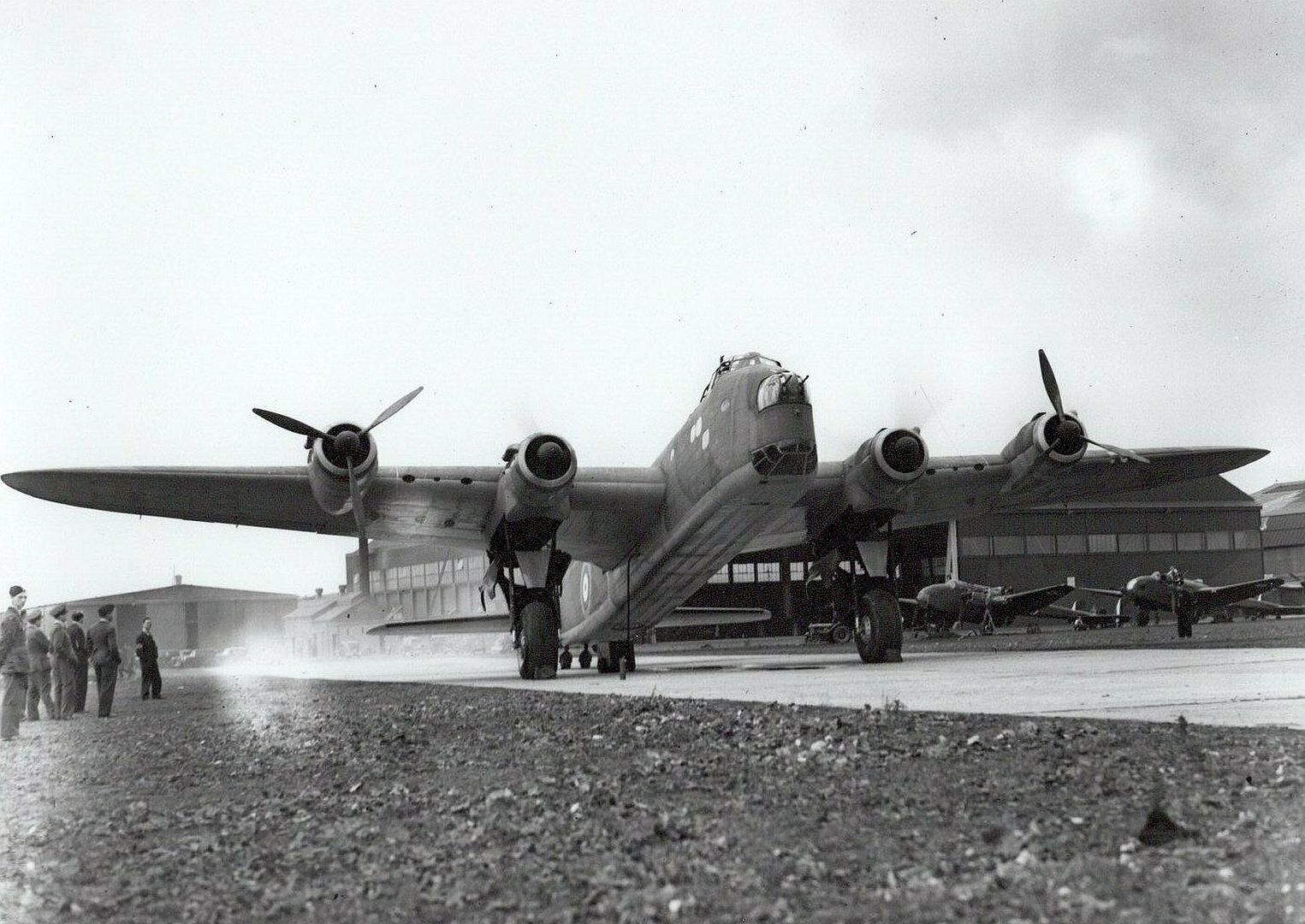

The finished version, Stirling Mk1, was renowned for its maneuverability in the air, and good all round visibility for the pilot. Its controls were tolerant, with ailerons of a surprising lightness for such a large plane. The elevator control was heavy and had a sluggish initial movement, but the overall handling qualities were of good directional and lateral stability once airborne, and a high rate of roll. There were, however, bad qualities which came as a result of too many last minute changes in the basic design.

Given enough development time, the Stirling would have been a faultless piece of fighting machinery. But the exigencies of war turned the test programme into a farce. The first 100 aircraft were on order by the Air Ministry before the prototype had even been built. Before the end of 1938, Hitler's march on Vienna hurried Britain into ordering another hundred. The machine had not yet flown, and they were still insisting on alterations to the design. Shorts had planned for a wing span of 112ft to give good high altitude performance. The Ministry cut it back to 99ft for the questionable reason that the doors of the standard Bellman hangar used by the RAF were only 100ft wide. It was a directive that spelt death for many an aircrew, for the Stirling's major fault was its inability to achieve a safe altitude.

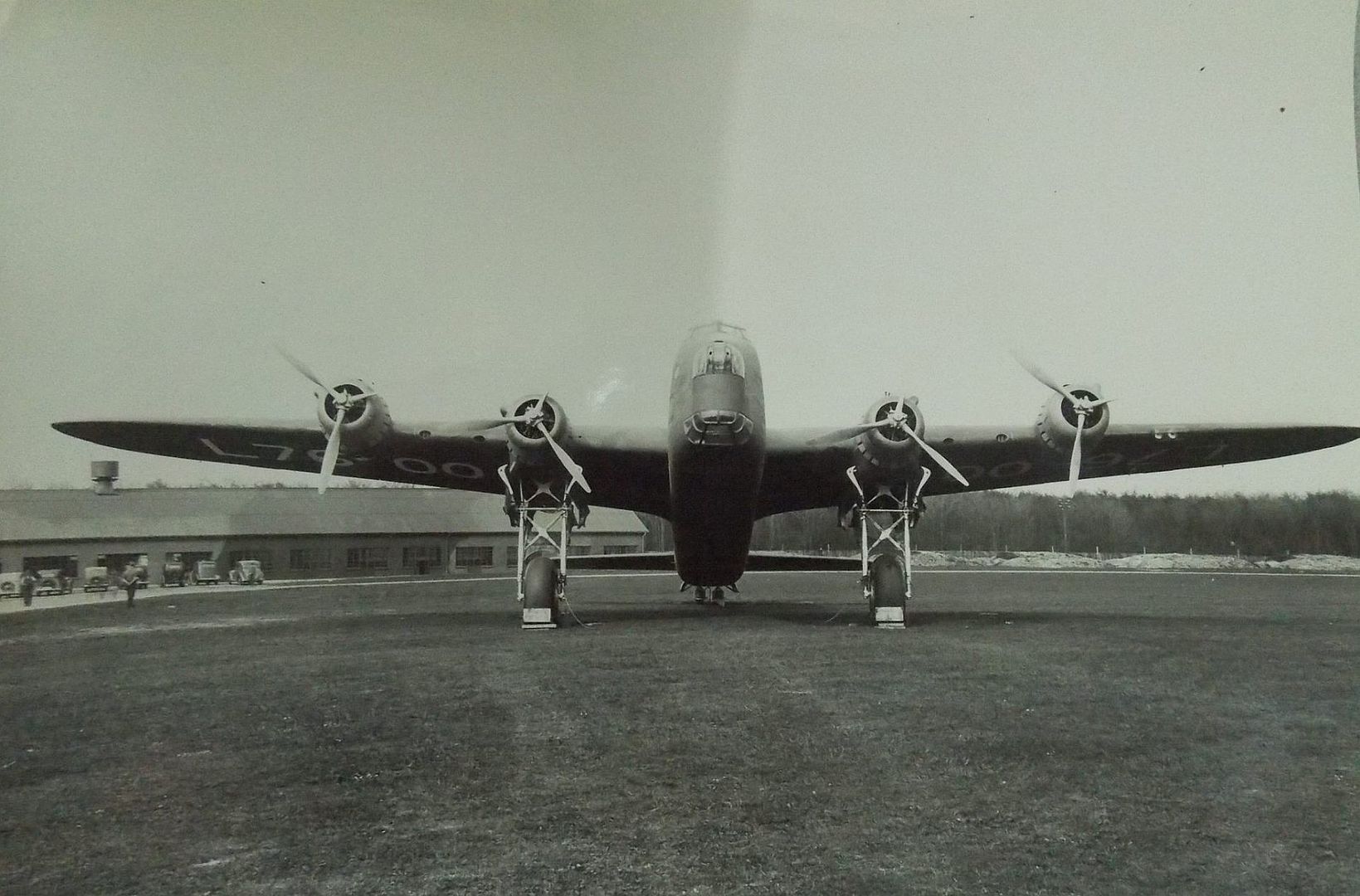

The shorter wing gave poor grip on the air, a factor which led the Air Ministry's test pilots to ask for improved take off performance once they had flown the half size mock up. They suggested increasing the angle of wing incidence by 3 over the 3 2 planned. By this time, design and tooling up were too far advanced for major alterations of this nature. A compromise was made. The undercarriage was lengthened, lifting the whole fuselage a further 3ft. This gave the plane the appearance of a praying mantis, and was responsible for a number of take off accidents. The longer legs were a constant source of irritation. An incident on 14 May 1939 put the programme back. As Lankester Parker put down the first prototype, L7600, one brake jammed and the extended undercarriage collapsed.

Seven months later, a second prototype, L7605, flew on Christmas Eve. The first production Stirling, M3635, was in the air only five months later. The aircraft had many useful innovations such as the Graviner switches which could be pressed to put out engine fires. Petrol tanks, with the exception of those in the wing root leading edges, were covered with latex rubber. This made them self seal when hit by bullets. The bomb doors were electrically driven, and the doors to release the bombs carried inboard of the engines were actually made to open into the wing. This meant that they did not disturb the air flow at a time when the pilot needed to fly a very steady course.

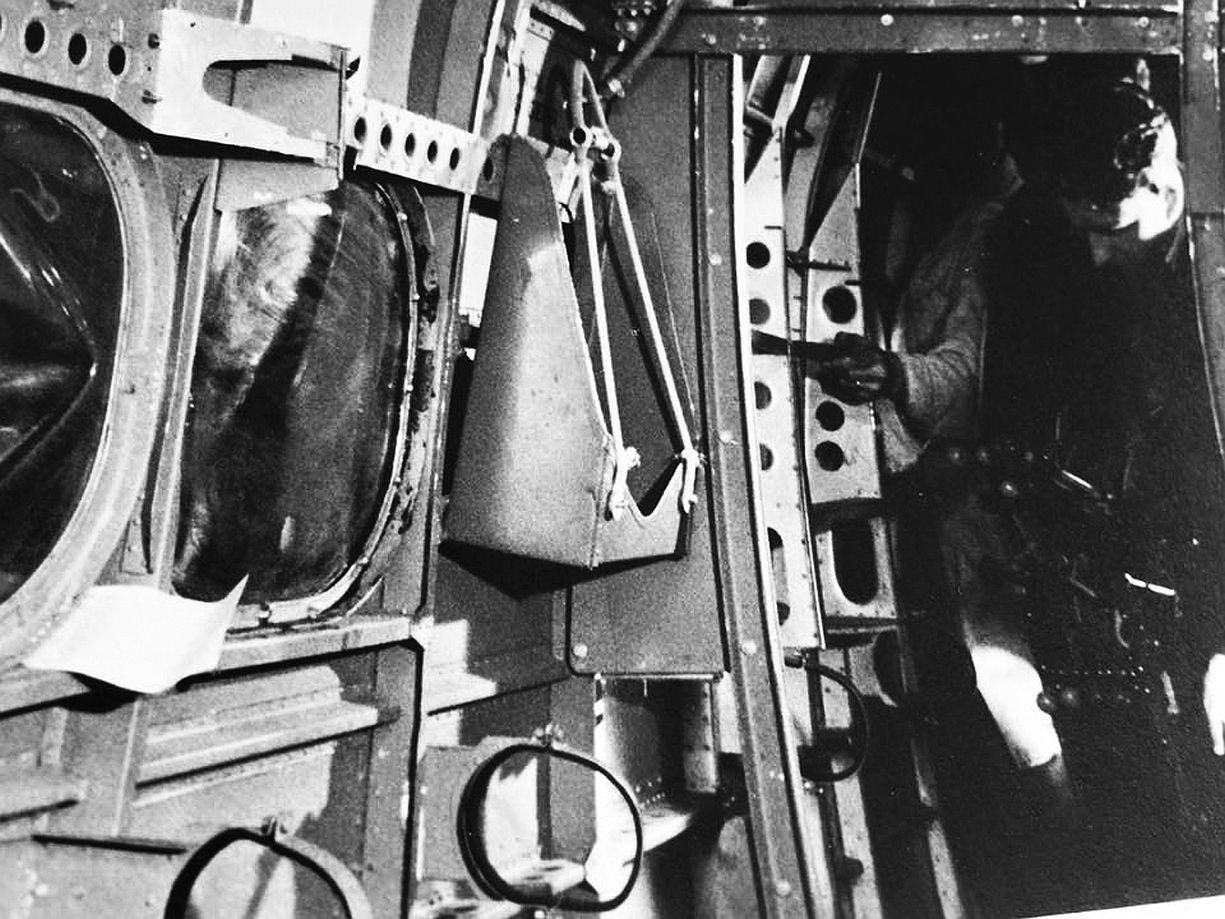

Amongst the good was the bad. Some of the Rochester built aircraft had been equipped with a ventral turret for fighter defence. The theory was sound, but in practice the turret when lowered gave a huge increase in drag. This reduced the aircraft's speed at a time when it was most needed. The non return hydraulic valves which operated the turret were inclined to leak, causing the turret to slip downwards. There were several accidents due to the guns fouling the ground during taxiing, so it was decided to discontinue the ventral turret and replace it with Brownings firing through side hatches.

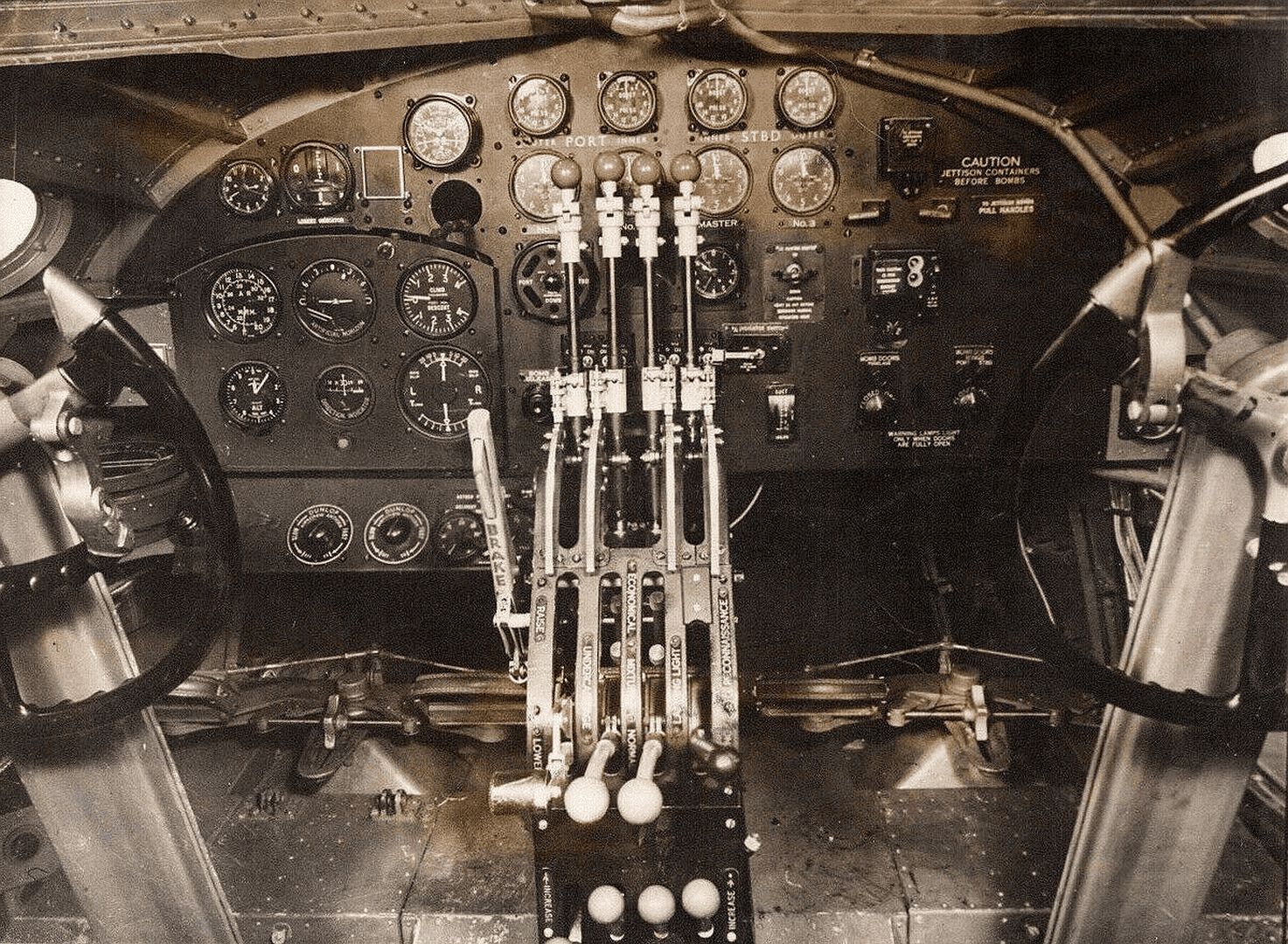

Taking off in a fully loaded Stirling was a hazardous business. There was no lack of power, but alterations ordered by the Air Ministry had upset designer Couge's original performance concepts. The aircraft was prone to violent swing as soon as it left the runway. The direction of the swing was unpredictable, and was responsible for the death of a number of airmen. The chief causes were lag in the hydraulics of the throttle controls and the length of the u/c. Pilots would set all four throttles to the same position but find the power units on one side giving many more revs than the units on the other. This would not be too bad with a normal throttle control, but the Exactor throttle linkage fitted to the Stirling was activated by a column of unpressurized liquid. It was slow to react, and sometimes did not react at all. Pilots had the terrifying experience of pushing the throttle levers hard forward without hearing any change in engine note, indicating an increase in revs.

Despite the faults, a regular flow of Stirlings began to come off the production lines at Rochester, Kent, and at Belfast, Northern Ireland. They were a marvel of teamwork. A squad of 600 engineers travelled around 20 factories all producing parts for the same bomber. This practice of wide dispersal followed a raid on 9 August 1940, where six completed craft, serial numbers N3645 and N3647 51, were destroyed in a factory at Rochester, Kent.

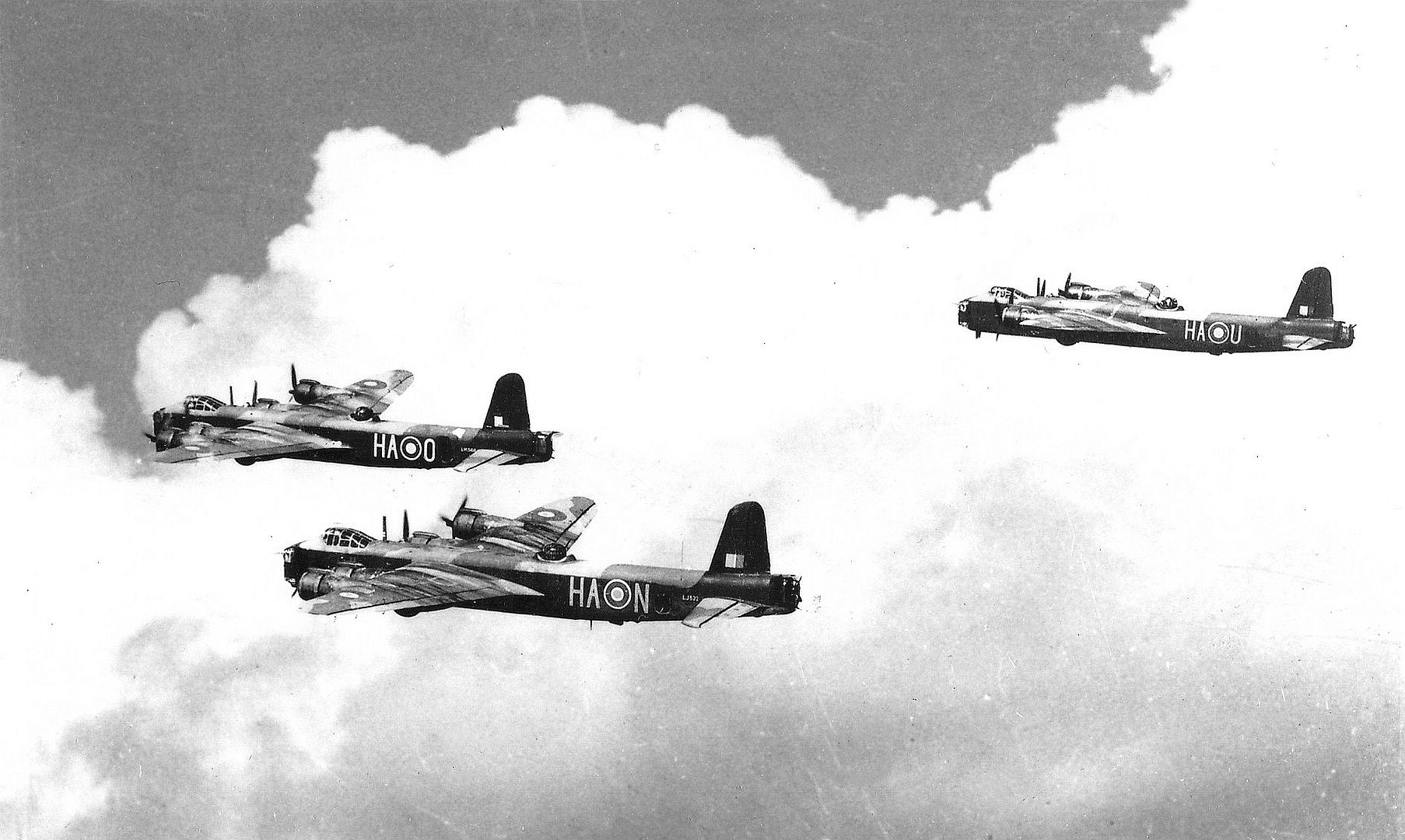

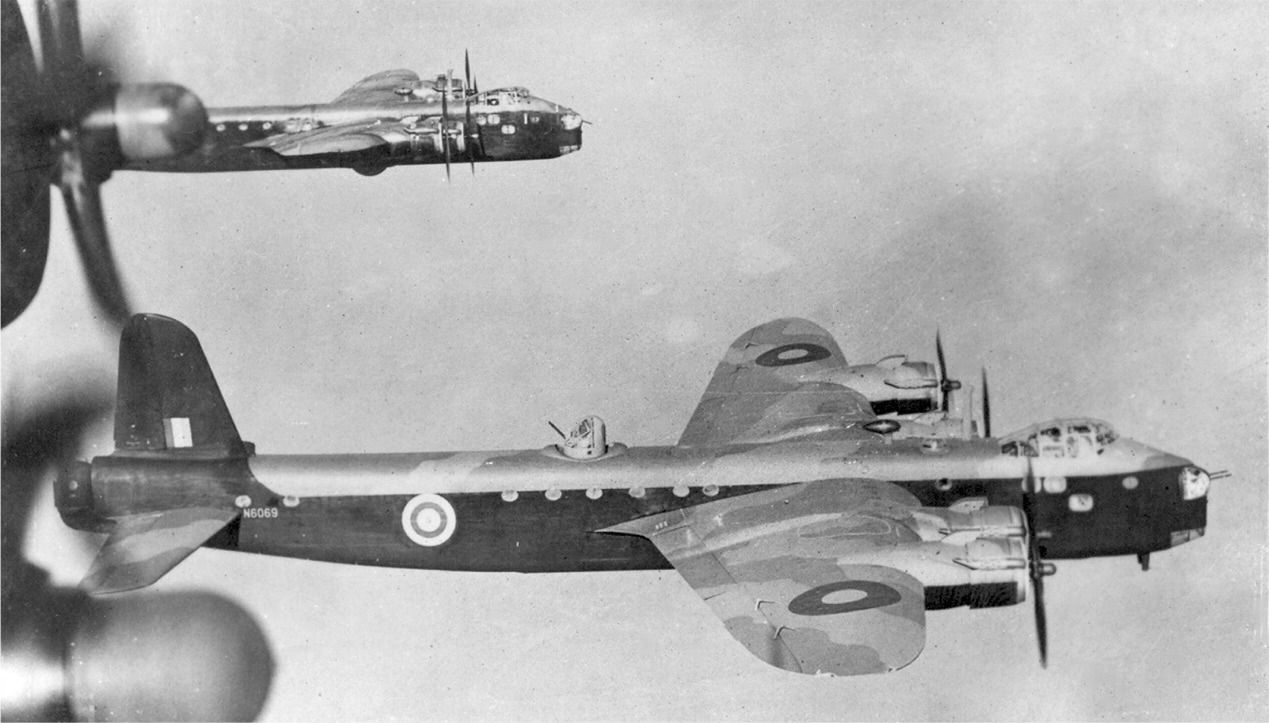

By the end of 1941, Shorts had produced 150 Stirlings which went to 149 Squadron at Mildenhall, 214 Squadron at Stradishall and 218 Squadron at Marham. These squadrons were mainly responsible for sowing acoustically and magnetically operated mines in such areas as the Kiel Canal, the Gulf of Lorient and shallow waters where German shipping operated and where the mines would be effective.

The plane was also considered able to take care of itself on daylight raids. One such was the famous raid on the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst, which had been bottled up in Brest harbor for much of 1941. Brest was well served by fighter stations and AA emplacements. The Stirlings, some from No 7 Squadron, went in first. A pilot's report,

published in a Ministry of Information booklet of 1943, said : "The town looked very peaceful in the strong sunlight. But when we were about four miles away, the whole sky suddenly filled with shell bursts. We flew straight in I have never seen such formation flying under fire. They were in unbroken line". This line contained an aircraft, N6086 LS-F, named "MacRobert's Reply" from No 15 Squadron. Lady MacRobert had donated $25,000 (then about $100,000) towards its cost in remembrance of her three flier sons. On the Brest raid the crew of "MacRobert's Reply" not only dropped a 2,000lb bomb down close to the target, but they also shot down a fighter.

Aircraft and operations are only as good as the people who operate them. In all the glorification of bravery, there is a tendency to forget that bravery relates to people. It is one thing to take to the air in a heavily armed, fast single seater fighter, built to attack. It is another thing to sit in a laden bomber liable to be attacked, knowing that your survival depends on the ability of the crew to work as an efficient team no matter the strain of combat.

The Stirling pilot was responsible for the lives of his crew. Once they were in the air social differences vanished. Crews of mixed races forgot their nationalities. There were instances of senior officers flying as crew to pilots of lesser, non commissioned rank and taking orders from a skipper wearing sergeant's stripes. It was Sergeant Pilot Bennett who gained the AFM by landing a blazing Stirling which had been strafed from tail to nose as it was on final approach. With two engines on fire and the cockpit filled with smoke, he could only see by smashing some of the top canopy glass, and standing on his seat to look out. How he controlled the aircraft must be conjecture. The landing was all the more astounding because the modifications to improve Stirling take off had the opposite effect,that of making it difficult to land. It used to "cushion" refuse to go down,and could only be grounded by heaving back on the column. How Sgt Bennett managed this whilst standing on his seat, only he knows.

Next in importance to the pilot was the navigator/bomb aimer. His main task was to pin point the aircraft's position, calculate the drift and ground speed, and make a timed run to his target. He had a bomb sight on which he could set all the variables,course, speed, drift, height and bomb ballistics. But this was possible only when he could see the target, or the glow from the flares dropped by Stirlings and other aircraft of the Pathfinder Force. A bomb dropped from 15,000ft at normal attack speed would land about 11 miles ahead of the aircraft, so the complexity of the job can be appreciated.

The roles of the other crew members were less glamorous but just as vital. For much of the trip the flight engineer was busy calculating the amount of petrol left in each of the 14 tanks in the wings. He pumped it from tank to tank to keep the craft in trim. His other responsibilities included the hydraulics, armament, and if the bomb-release mechanism failed, he crawled into the bomb bay to try to free hung up bombs.

The odd man out was the rear gunner. He was stuck 20 yards away from the rest of the crew and could be alone for as long as eight hours. The rear gunner "Tail end Charlie" could never relax. He sat watching the huge expanse of sky, alert for fighters, AA fire and also checked the accuracy of his and other aircraft's bombs.

An unfortunate factor in early Stirlings was the position of the motors that operated the turrets. These were sited immediately behind the roundels on the fuselage. German fighter pilots soon learned that a hit there would put the turrets out of commission and even cut the intercom to the rear gunner. This meant that he could not advise the pilot on what evasive action to take. It was after such an attack that a Messerschmitt cut across a Stirling's tail and very nearly severed the rear turret from the aircraft. For three hours the battered Stirling limped across France back to England. The turret sagged a few inches lower as each mile slid by. With every vibration it looked like dropping off. There was no way that the crew could reach the gunner. He was trapped and could only sit and wait for him and the turret to fall off. But by gentle flying the pilot put the plane on the runway. The rear turret, with the gunner inside, rolled away like a football. He stepped out unscathed, but never flew again.

The crew of P for Peter took off from Mildenhall bound for Turin. Here, the AA defenses were not good but there was the Alps for protection at a distance too close to the target for the returning Stirlings to climb above them with any certainty. A crew had a one in four chance of not coming back, so the "Peter" men performed all the good luck rites. The crew had done everything possible to ensure a safe operation.

"He vanished . . . I was not pleased"

Tension grew as they began their attack on the target. The rear gunner warned of fighters astern. There was no alternative for the captain but to drop his bombs and take evasive action by losing height fast. As the aircraft flattened out over the outskirts of the town, two tall chimneys appeared before him. They were 200ft high and about 120ft apart. It left a bare 10ft between each wing tip and the chimneys. Holding his breath, the pilot aimed between them. There was no time to bank away. But the gap was too narrow for the German trying to cut inside the bomber's line. He smashed into the chimney and crashed. Then P Peter's inner starboard engine seized up and the airscrew fell off. A piece of the debris smashed the tailplane. At the same time, a second Messerschmitt crossed broadside. Its cannonfire set the Stirling's port outer engine ablaze, and ripped off the wing tip. Worse still, a cannon shell exploded against the radio bulkhead on the flight deck and smashed all the instruments and the cabin was filled with smoke, which got into badly fitting oxygen masks. In their state, it was impossible for the crew to attempt to fly over the Alps. They would have to fly through. The rear gunner, unaware of this as another fighter screamed into the attack, said : "I was cold, dead cold as he came in. As I squeezed the trigger, there was a blue flash and he vanished. Just vanished! I was not pleased. I was angry. I thought, there are ten thousand rounds aboard this tub. The next bastard gets the lot."

The front gunner left his position to tend to the co pilot's burns. He found a torch and threaded his way aft. The stench of blood and urine told him that the flight engineer had been ripped apart by a shell. In the dorsal turret the mid gunner seemed to be resting. A fag was burning in his hand. I pulled on his flying suit to attract his attention. He fell on top of me. By this time the pilot could hardly keep the plane in the air. They lashed a couple of parachute straps around both control columns and heaved back on them. Somehow the flat plain of Southern France appeared beneath the Stirling. They were going home.

The two Stirling pilots who won VCs did so in the knowledge that they had no chance of getting home in one piece. On the night of 28 November 1942, Flight Sergeant R. H. Middleton, RAAF, was wounded over Turin in Stirling H Harry, and lost consciousness. His right eye was destroyed by a shell splinter. When he came to, he again took the controls of his craft, and ordered the crew to bale out. All did so except his two closest friends. They stayed with the aircraft, which crashed into the sea. The pilot's body was washed ashore two months afterwards.

Nine months later, on the night of 12 August 1943, Flight Sergeant A. L. Aaron was piloting EF452, O Oboe, of 218 Squadron over the smoke of Turin. During a fighter attack the aircraft was hit badly. Bullets smashed Aaron's jaw, tore away part of his face, perforated a lung and broke his right arm. But he carried on flying the machine until he was too weak, and then directed his flight engineer to what he hoped was a landfall in Sicily. They completely missed their target and eventually put down at Bone in North Africa at 0600 on 13 August a Friday. Nine hours later Aaron died.

The Turin and other Italian operations, together with the adventures of those 1942 nights when 1,000 British bombers took to the sky, were the highlights of Stirling operations. But the same year decided the fate of the Stirling. Despite its load carrying capacity and its ability to take punishment, it was gently phased out of Bomber Command whose Lancasters were proving highly efficient aircraft. The Stirling's low service ceiling of 18,OOOft was an embarrassment. Improving flak accuracy was forcing bombers to fly high. On large raids enemy fighters would ignore the high flying Lancasters and Halifaxes and concentrate on the Stirlings. The crews of other bombers would cheer when they heard that the Stirlings were on the same raid. "We acted as a sort of low level cover for them" commented the CO of Mildenhall.

Flying below the main force, the Stirlings were also vulnerable to falling bombs. There is more than one recorded instance of a bomb passing right through the fuselage of a Stirling, which somehow still managed to make its run to the target and get back home. One got far enough to allow its crew to bale out over Southern England. The pilot ditched in the Thames Estuary. Finding himself in shallow water, he waded a mile to the shore. On arrival he woke up a very surprised member of the Home Guard, who had gone to sleep safe in the knowledge that his stretch of beach was protected by an impassable 400 yards containing anti-personnel mines and many explosive devices.

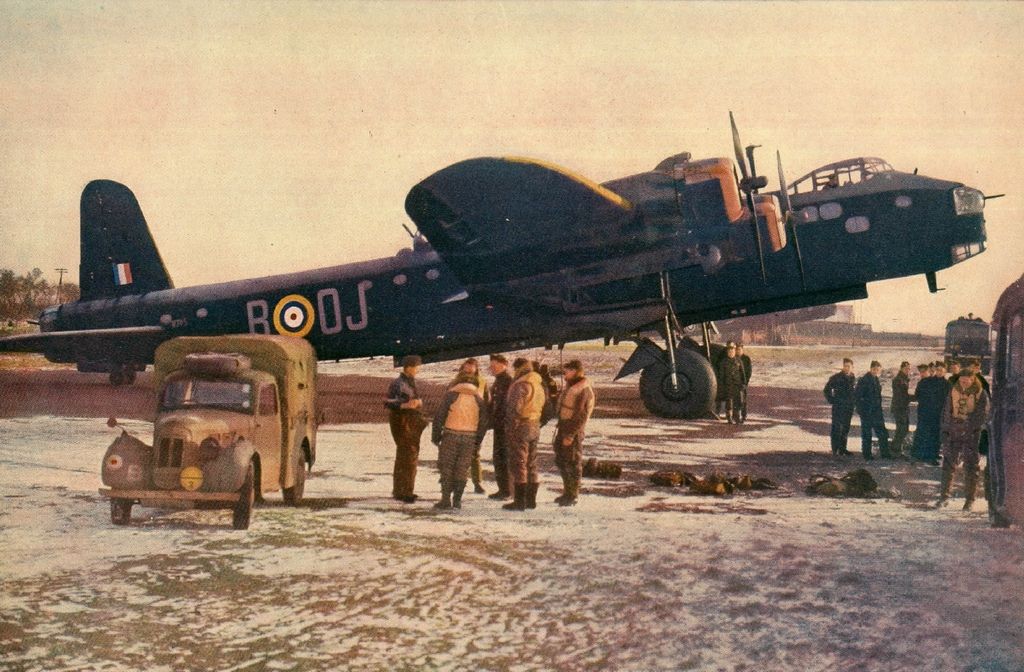

Ditching near home territory was obviously less perilous than coming down abroad. Stirling OJ Orange, Serial N3752, based at Lakenheath, Suffolk, droned on through the night of 16 May 1942. Its crew searched, without success, for the Kiel Canal. Carrying four 15001b sea mines, OJ Orange and five other 149 Squadron aircraft were originally part of a 500 bomber raid bound for Hamburg, but the raid was cancelled due to bad weather. Only the 149 Squadron aircraft took off OJ Orange flew on through the mist and rain.

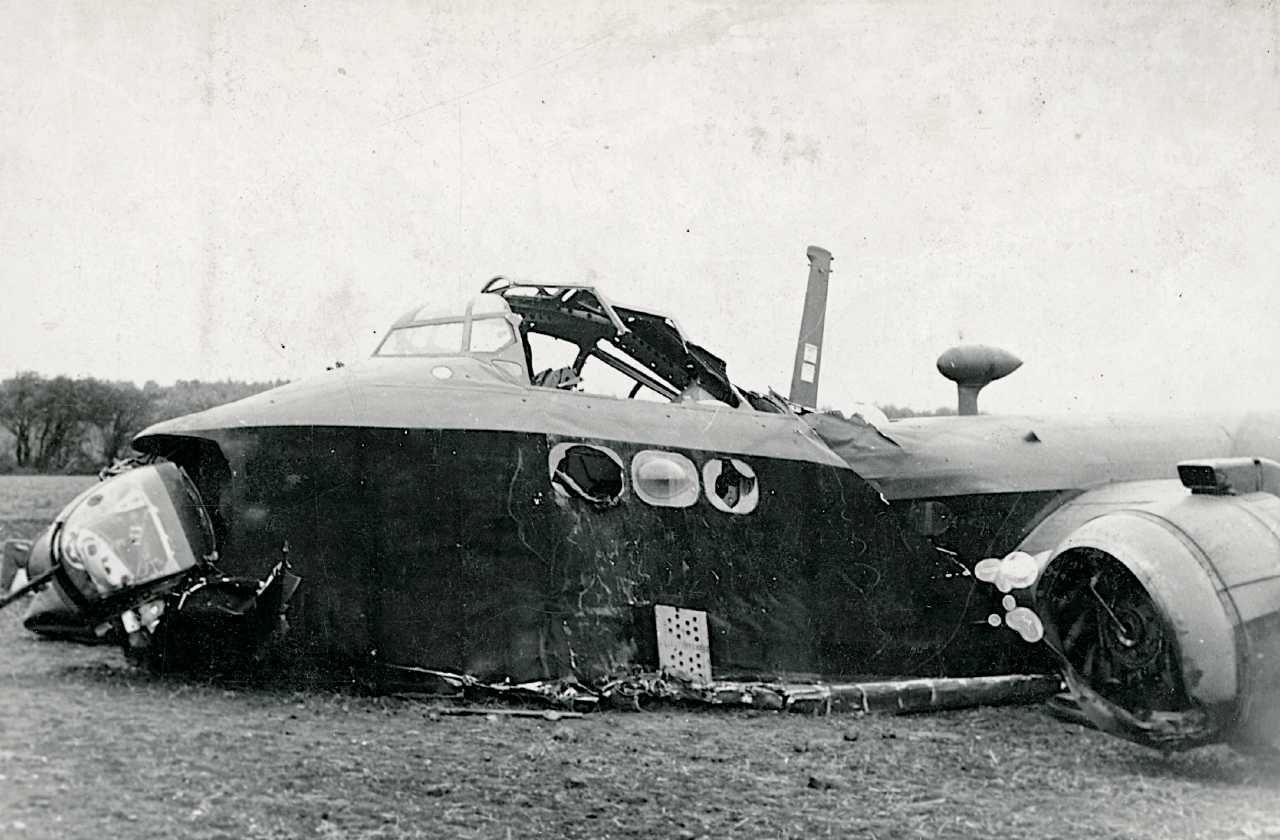

It was not a very comfortable ride. Kiel had low cloud cover. The captain, Flight Sergeant J. A. Jerman, decided to divert to a secondary target in NE Jutland, and crossed low over Denmark. Too low. Orange ploughed into the top of a small hill. Two of the crew, the navigator and flight engineer, were injured and were dragged out into a ditch. The rest of the crew tried to set the aircraft ablaze, a hazardous operation. Petrol was leaking from every tank.

A farmer named Jepsen saw the flames and alerted the civil rescue services and the German military. These took a long time coming owing to security. No one dared to take any risks in an area of Denmark which had been German until 1920, and where many people were pro Nazi. Detective F. Kvaendrup from the CID of Aabenraa, was not so favorably inclined towards the Germans. While pretending to examine the area to decide the claim for war damages, he photographed the crashed bomber even though it was guarded by a German sentry. The roll of film and news of the fate of the air crew were smuggled back to England.

Stirlings were transferred to RAF Transport Command during 1943, and extensively used for Special Operations Executive duties. Their main task was dropping supplies to the Resistance. Crews were not happy about this job. The enemy was often aware of the dropping zone and would lie in wait for a bomber, from which most of the guns any unnecessary weights had been stripped to increase the pay load. A lot of the supplies were parachuted, but one firm in England specialized in making tough wickerwork baskets which were dropped without support.

By D Day, 1944, Stirlings were engaged on dropping "Window" strips of tin foil designed to fool German radar. Mark V Stirlings, which had their dorsal and nose turrets removed, also towed up to five Horsa gliders carrying Allied troops inland behind the enemy lines, and were used to drop dummy "parachutists" which had German forces rushing away from the actual invasion area. These "parachutists" emitted machine gun noises and delayed explosions which caused the Germans to rush back to the area several hours later.

For the Stirling, action was not yet over. Its last bombing raid took place on 8 September 1944, when 149 Squadron bombed the French port of Le Havre. As late as September 1944 at Arnhem a Stirling squadron was crippled while dropping supplies to paratroops. The tragedy of these losses is that most of the equipment was dropped on enemy held territory.

The Stirling Mark V a transport plane was brought into service in January 1945 with 46 Squadron, Transport Command, to carry equipment and personnel to the Far East. The A Bomb finally put an end to these trips. The Stirling was redundant. Over six years a total of 2,371 Stirlings had been built and they had flown 18,440 sorties. By May 1947 only 12 remained intact. The rest had been scrapped. Now, there is not a Stirling to be found.

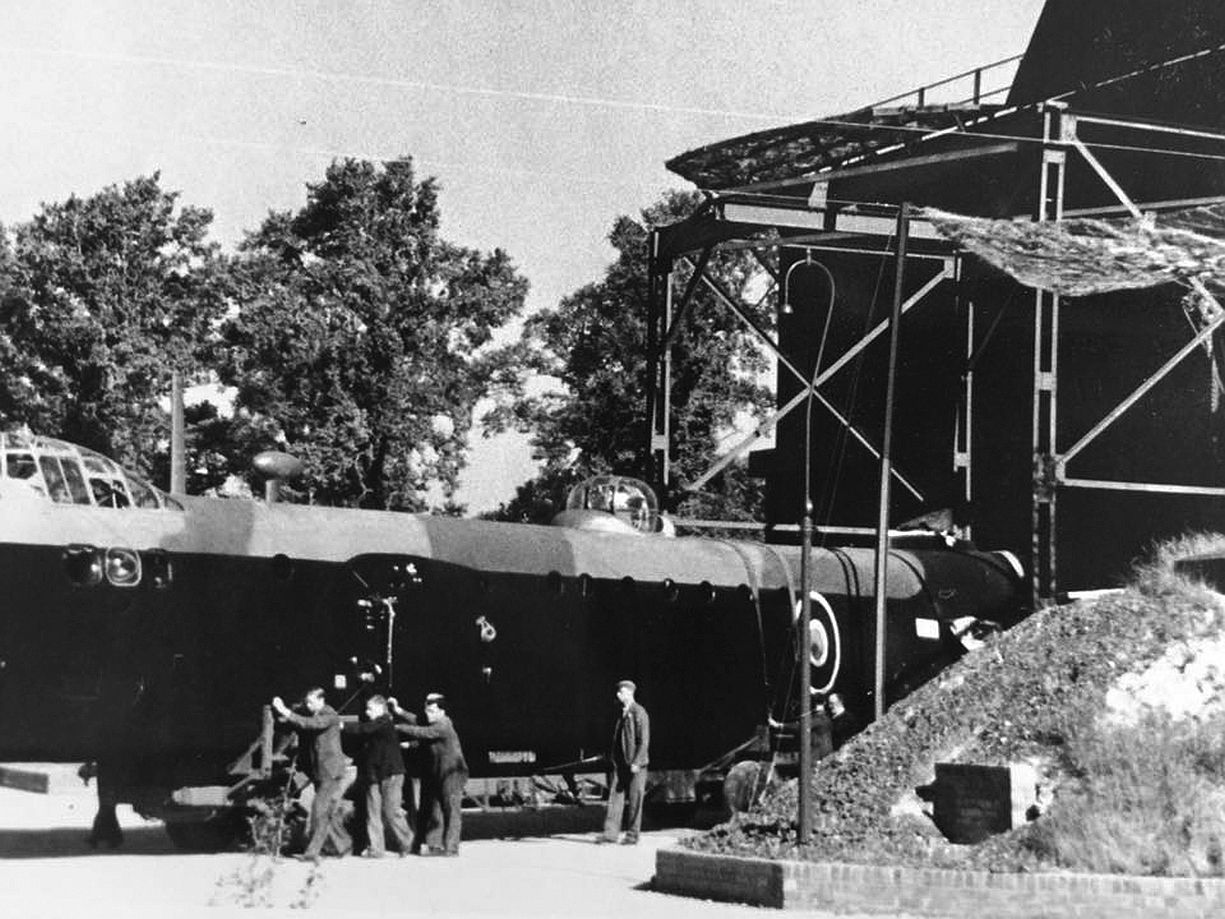

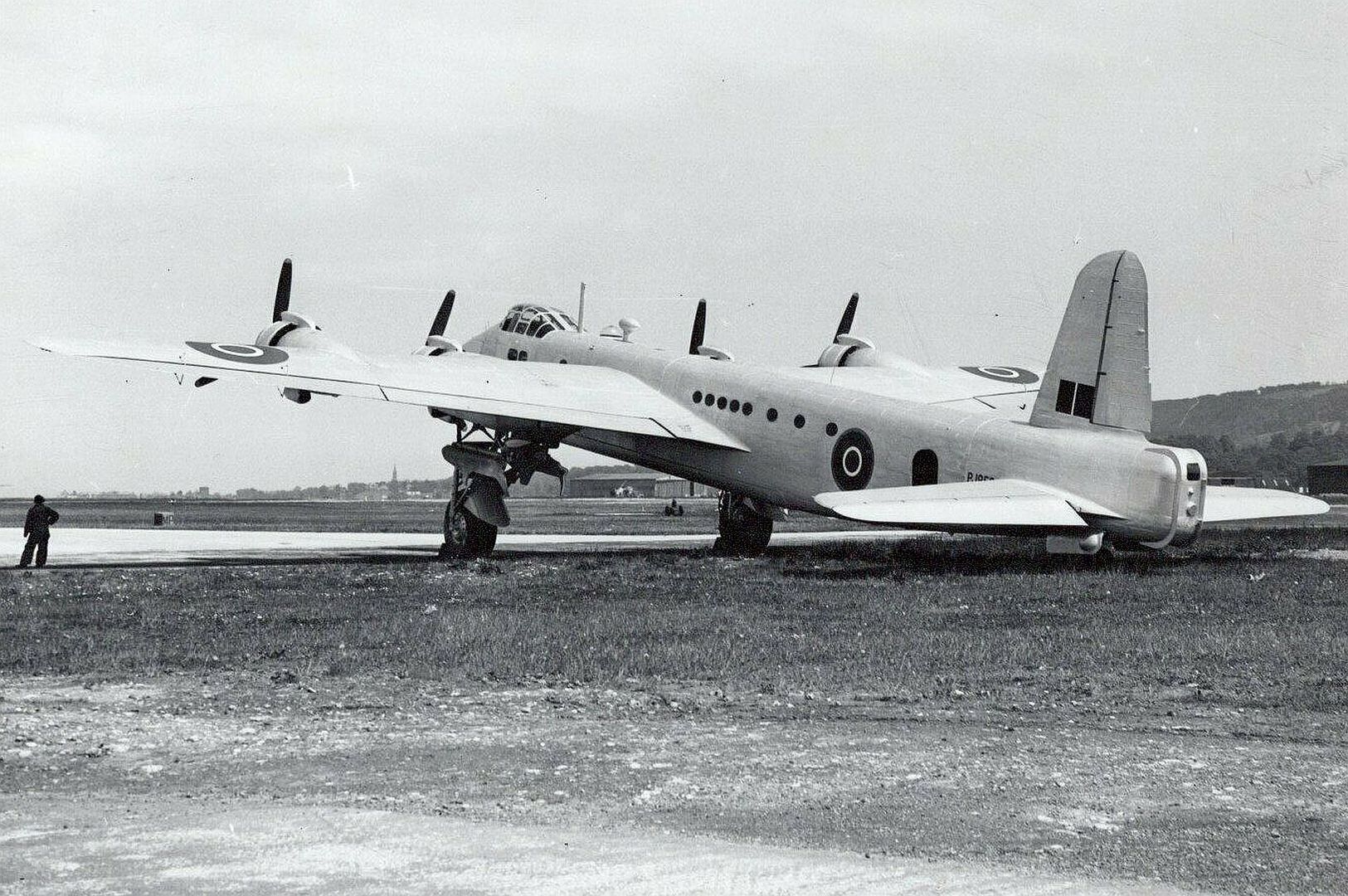

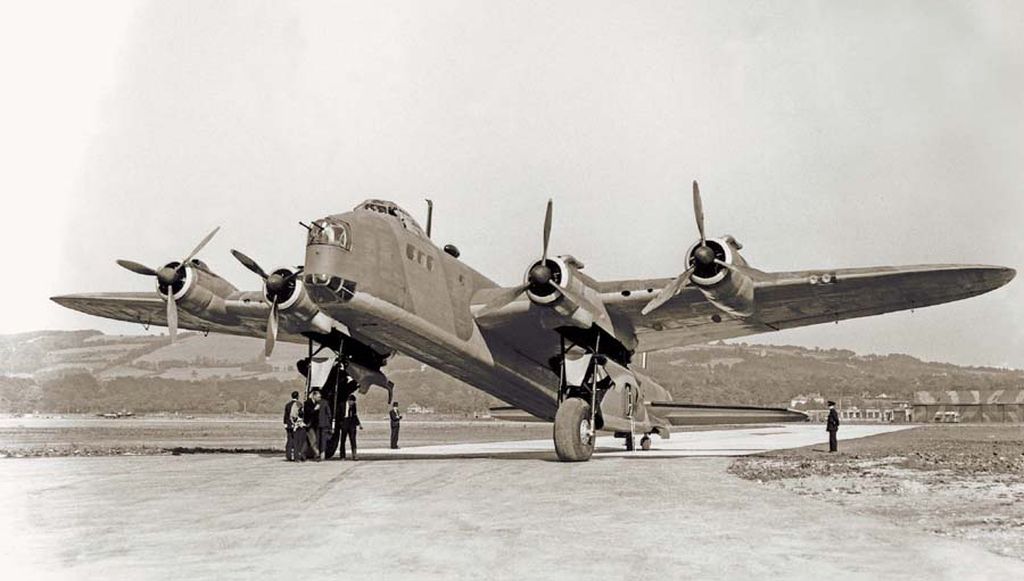

Below prototype

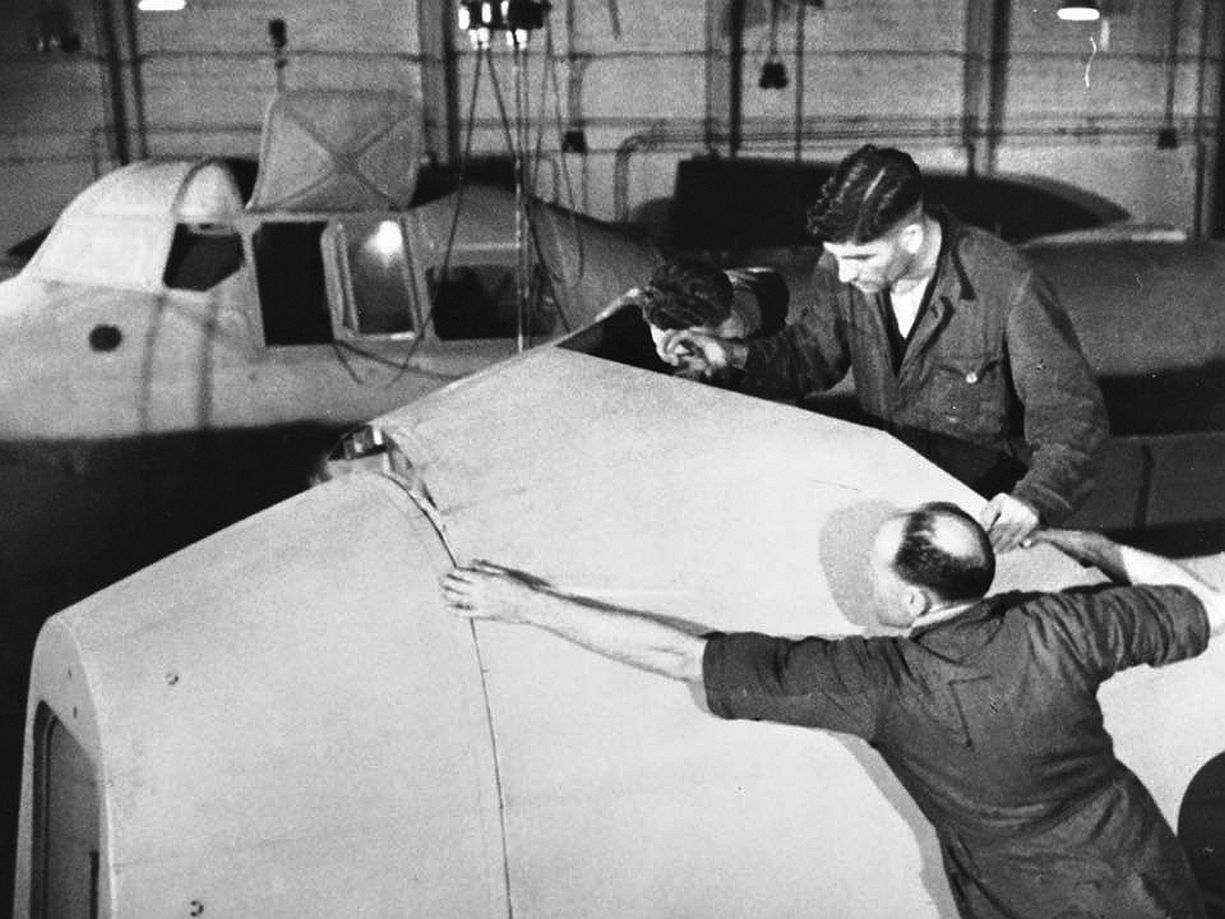

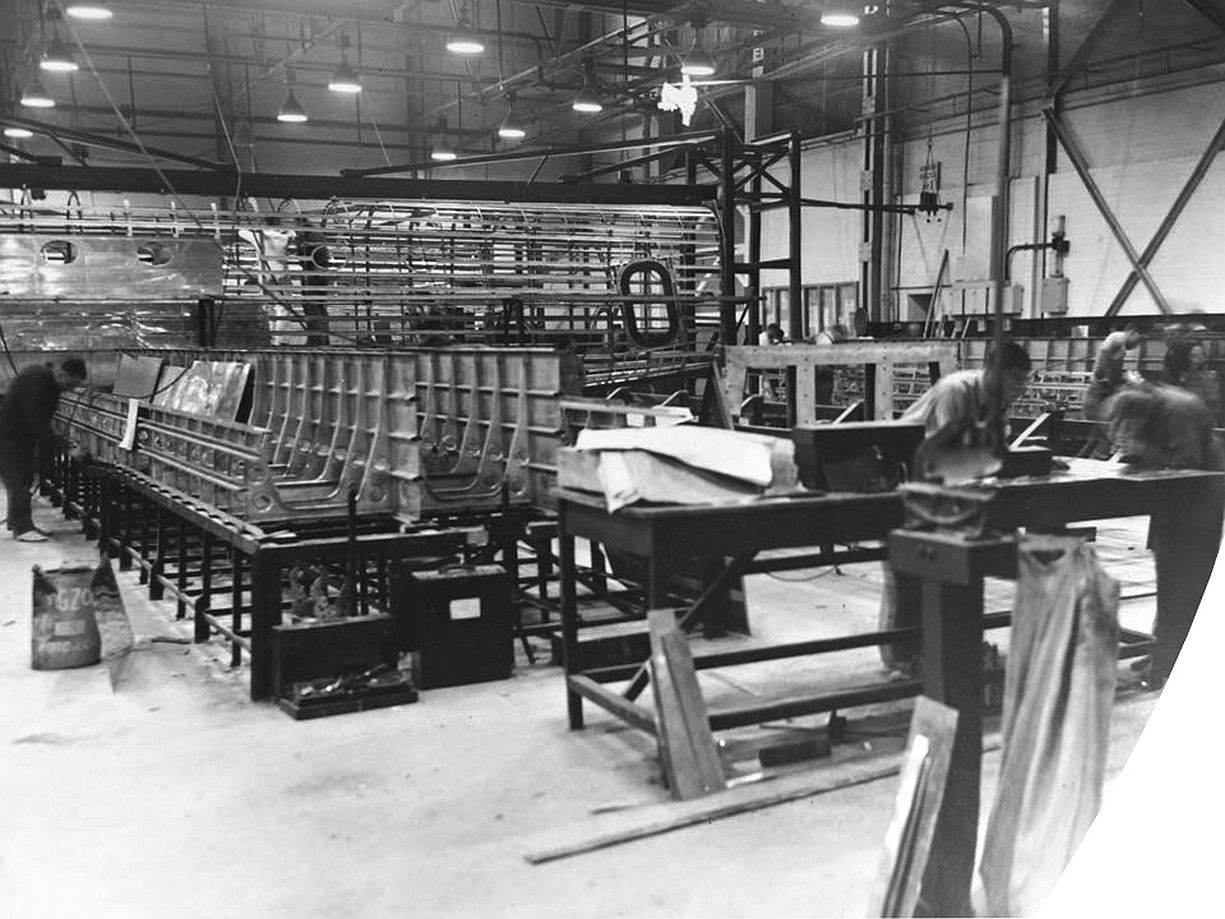

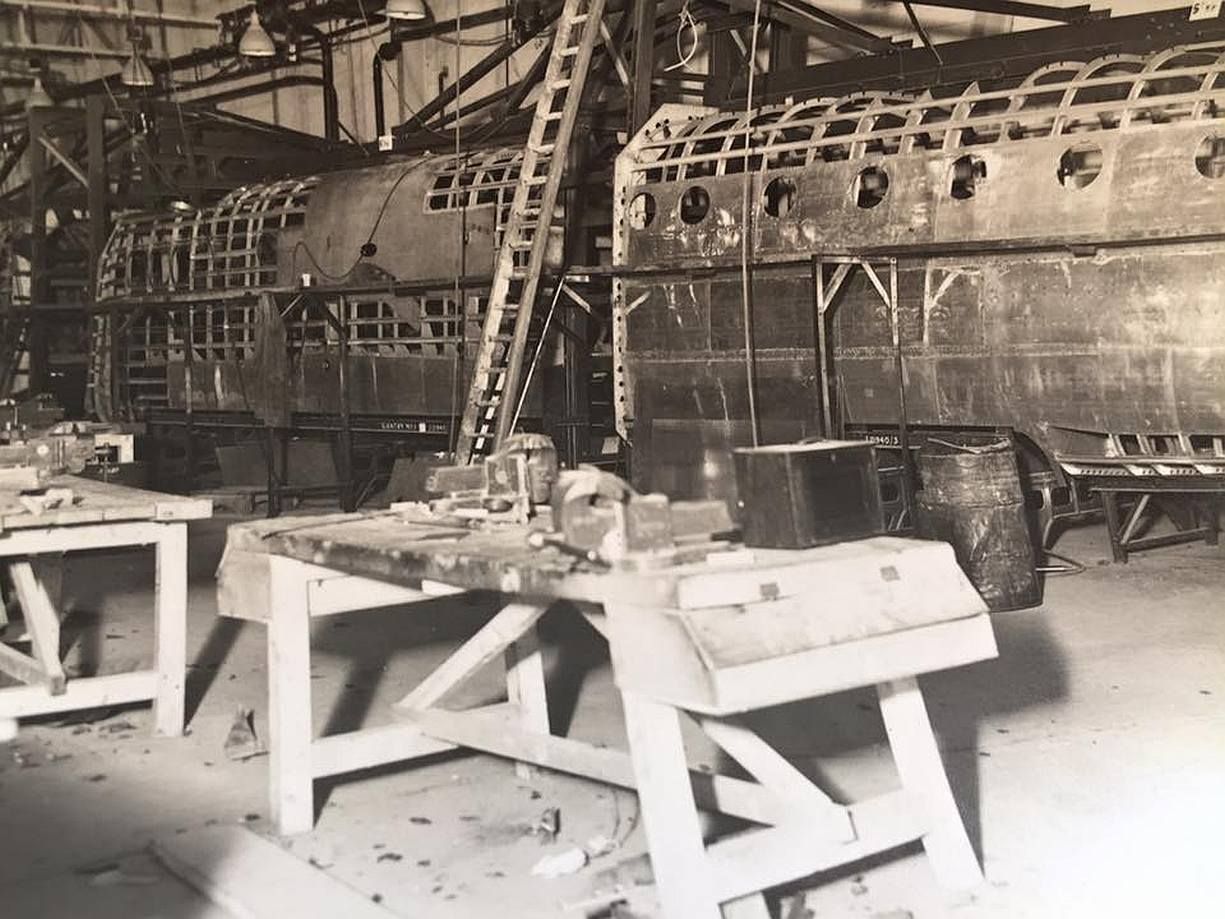

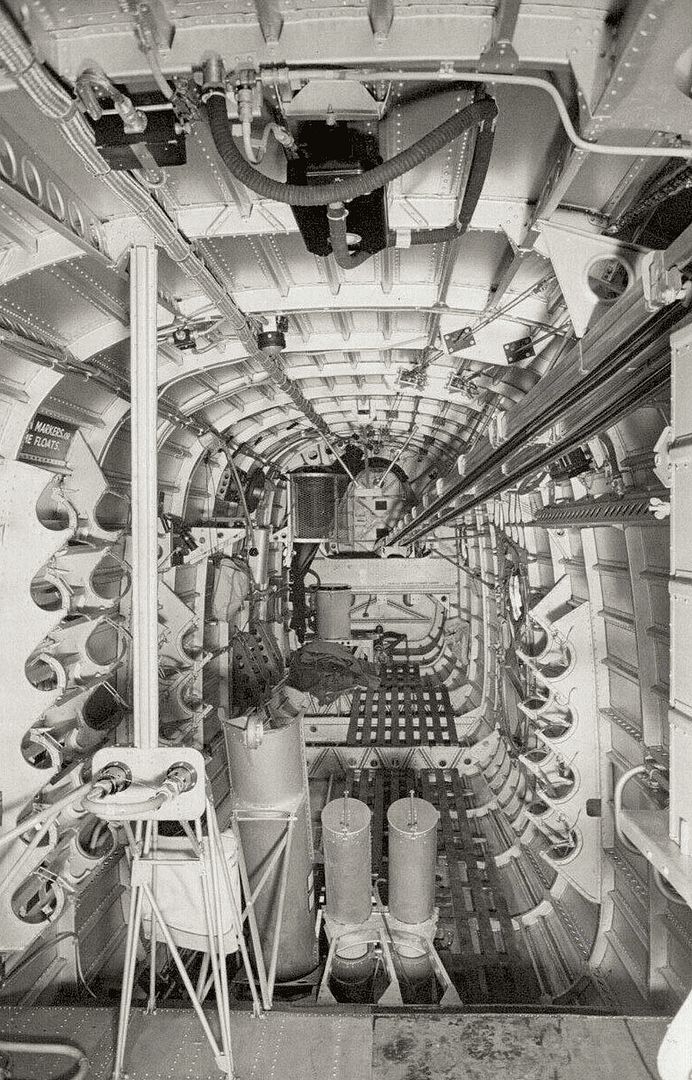

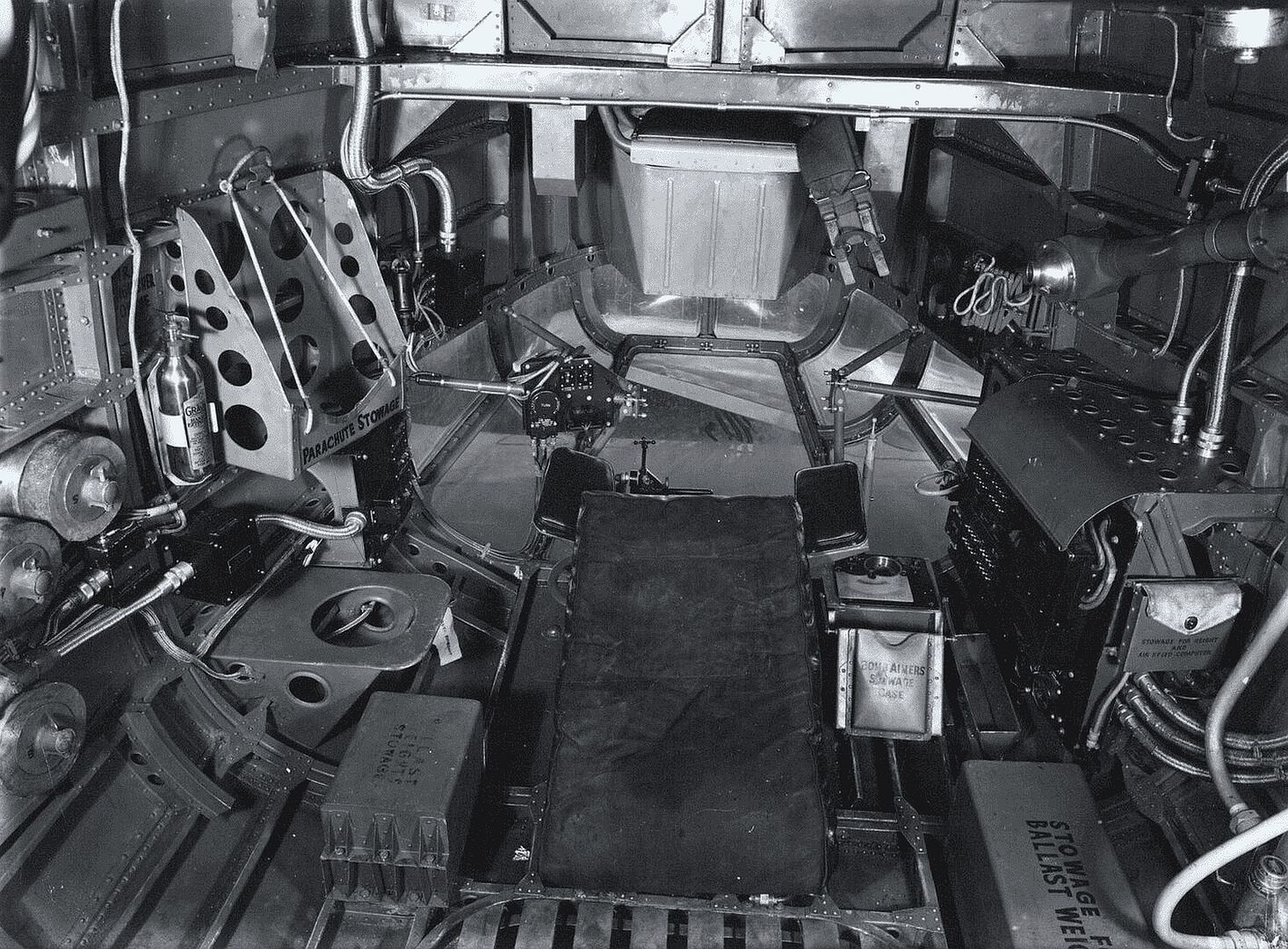

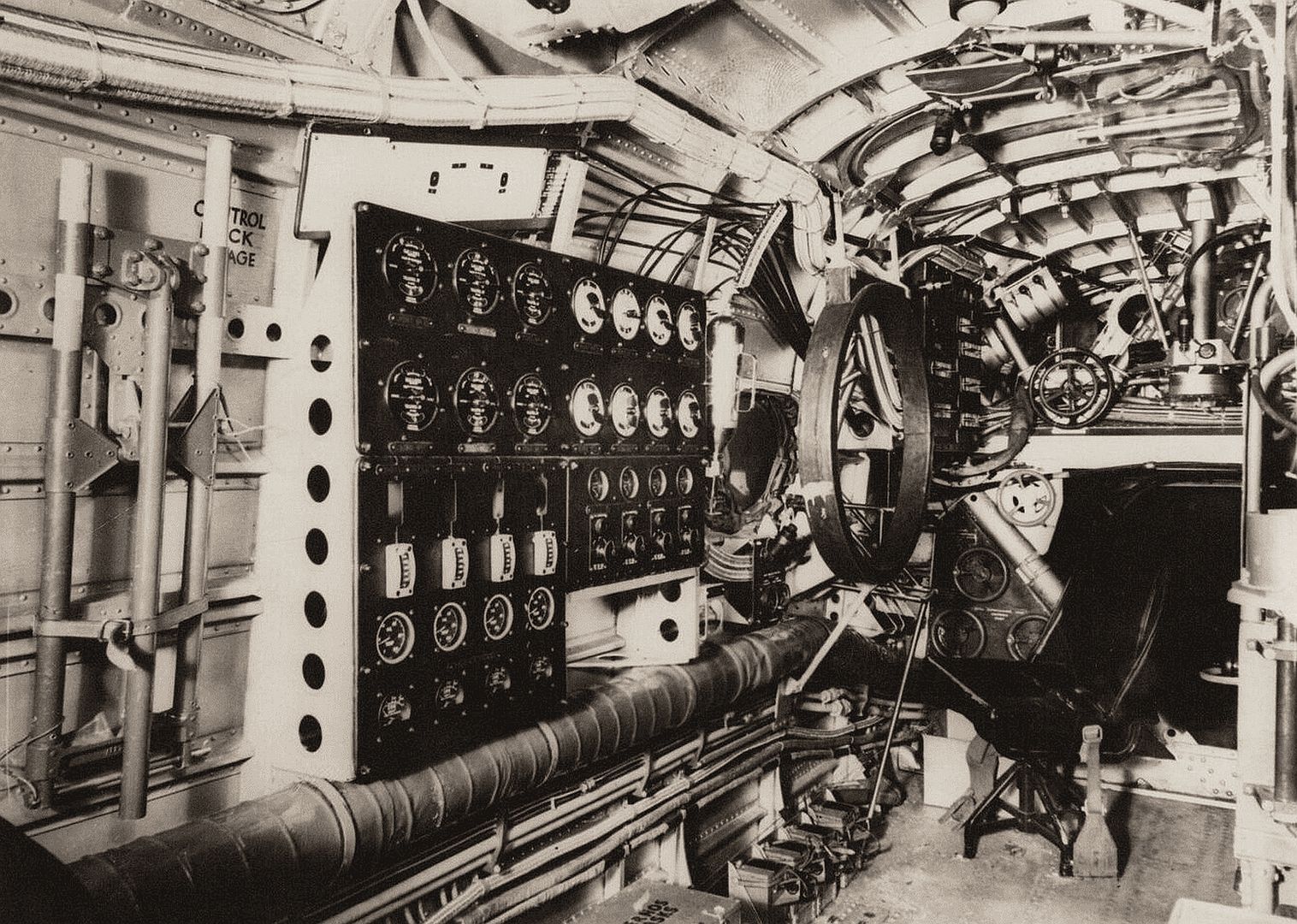

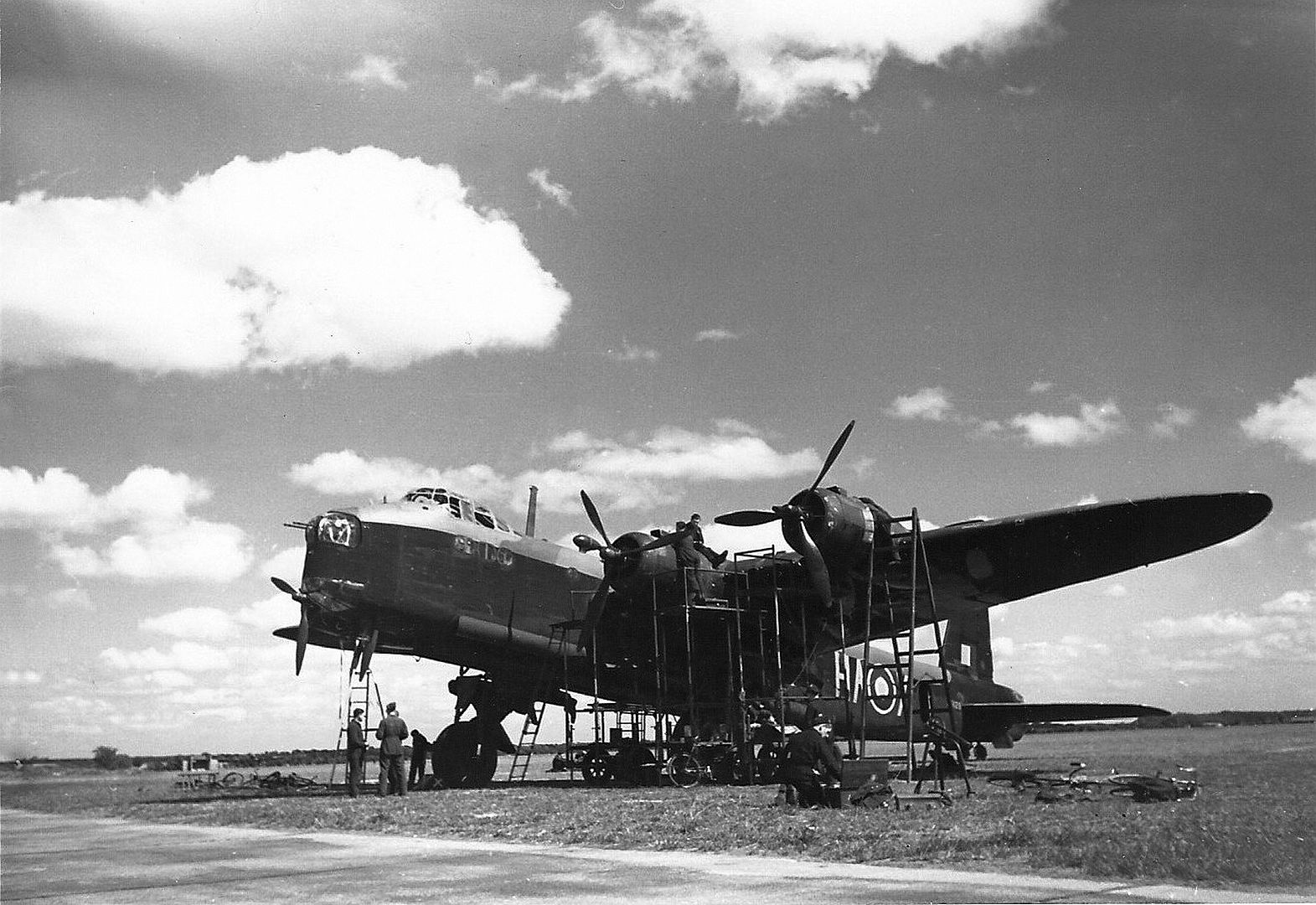

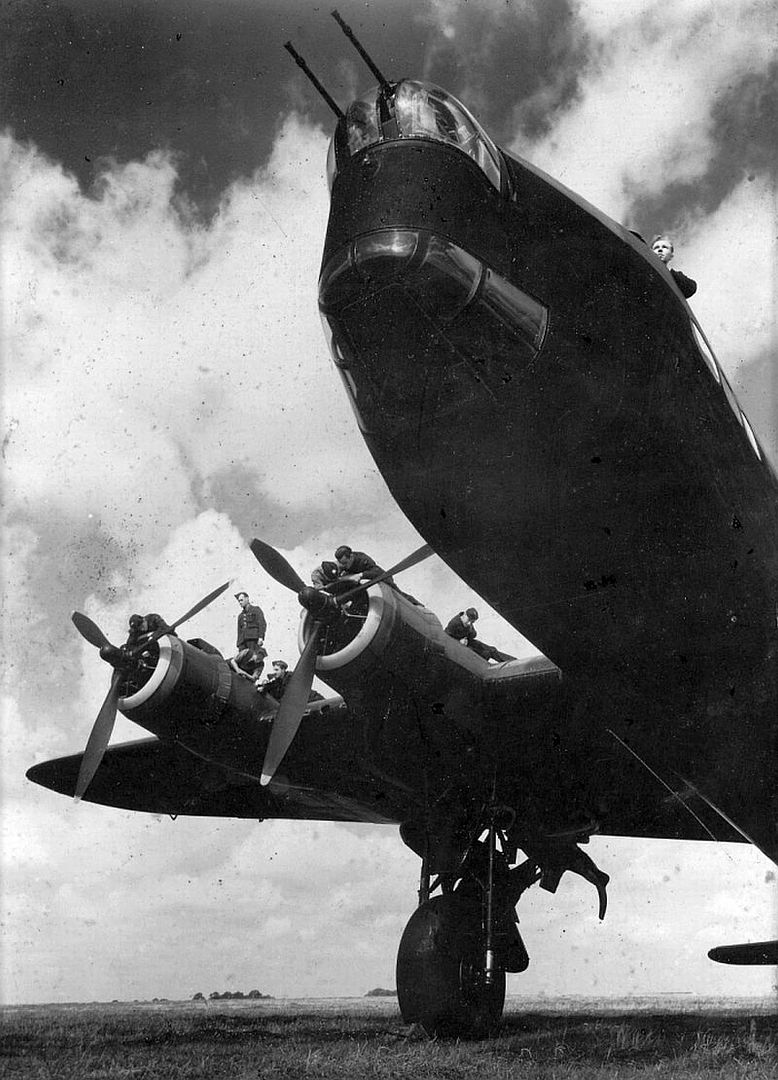

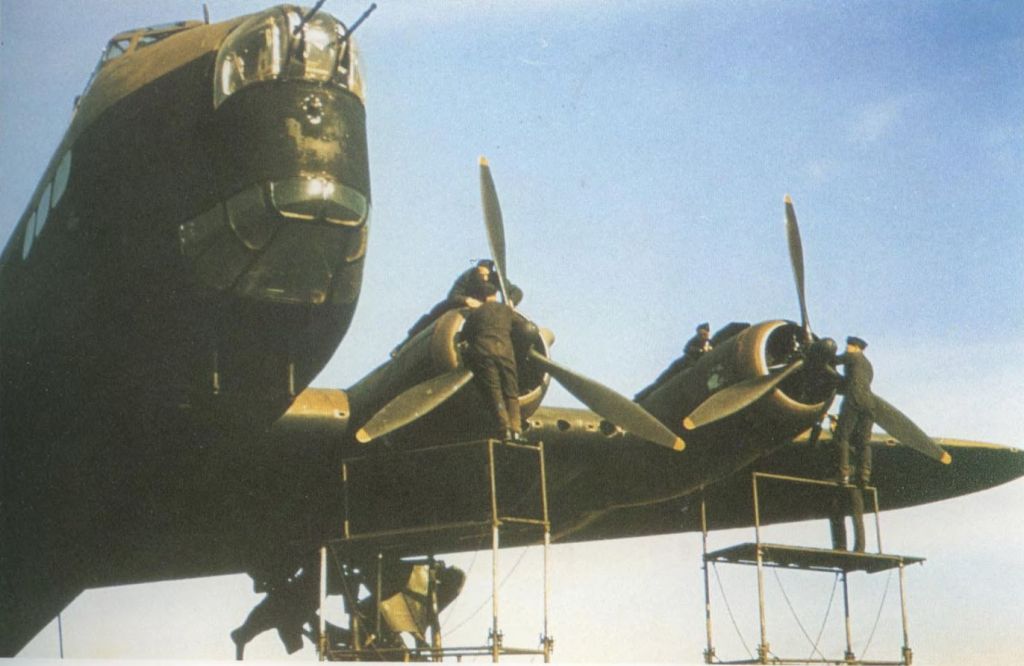

Below construction

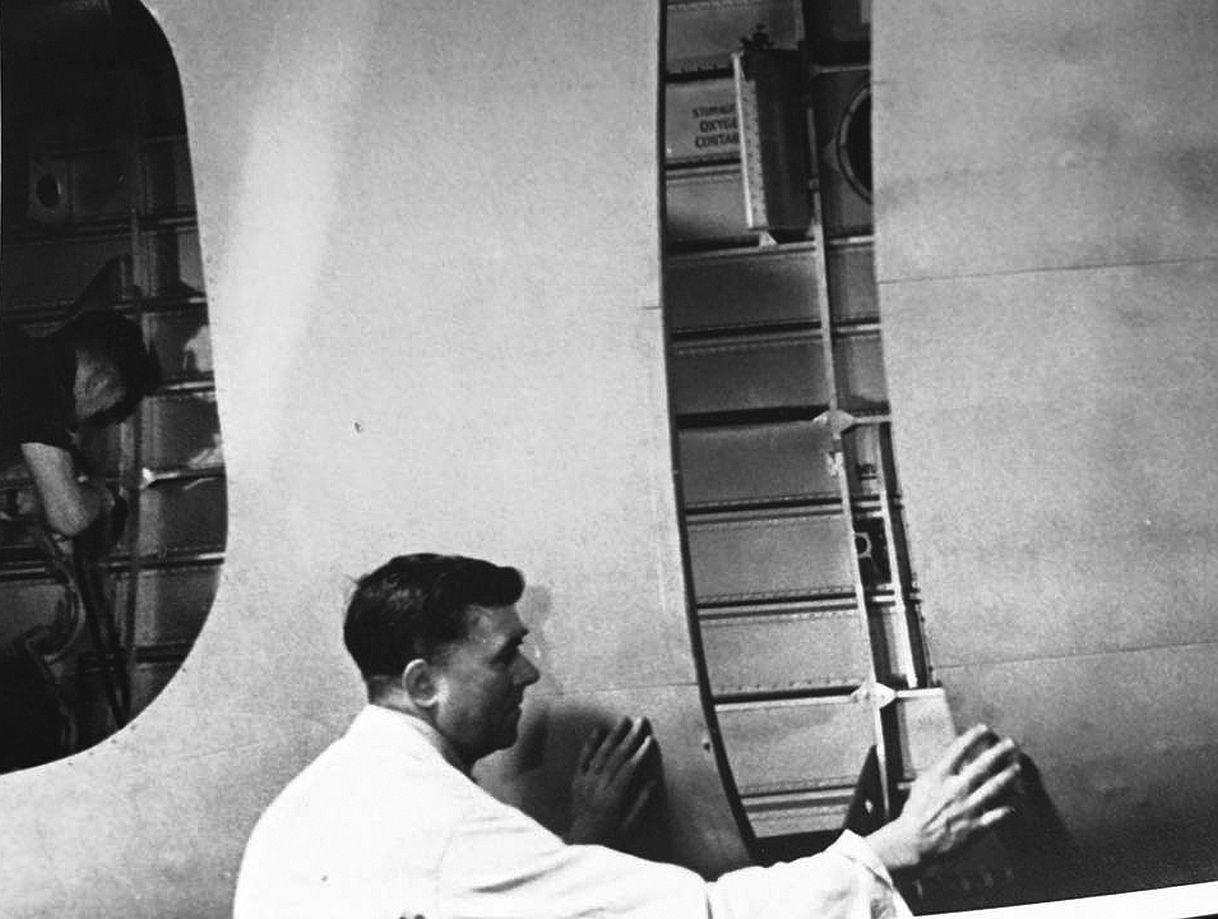

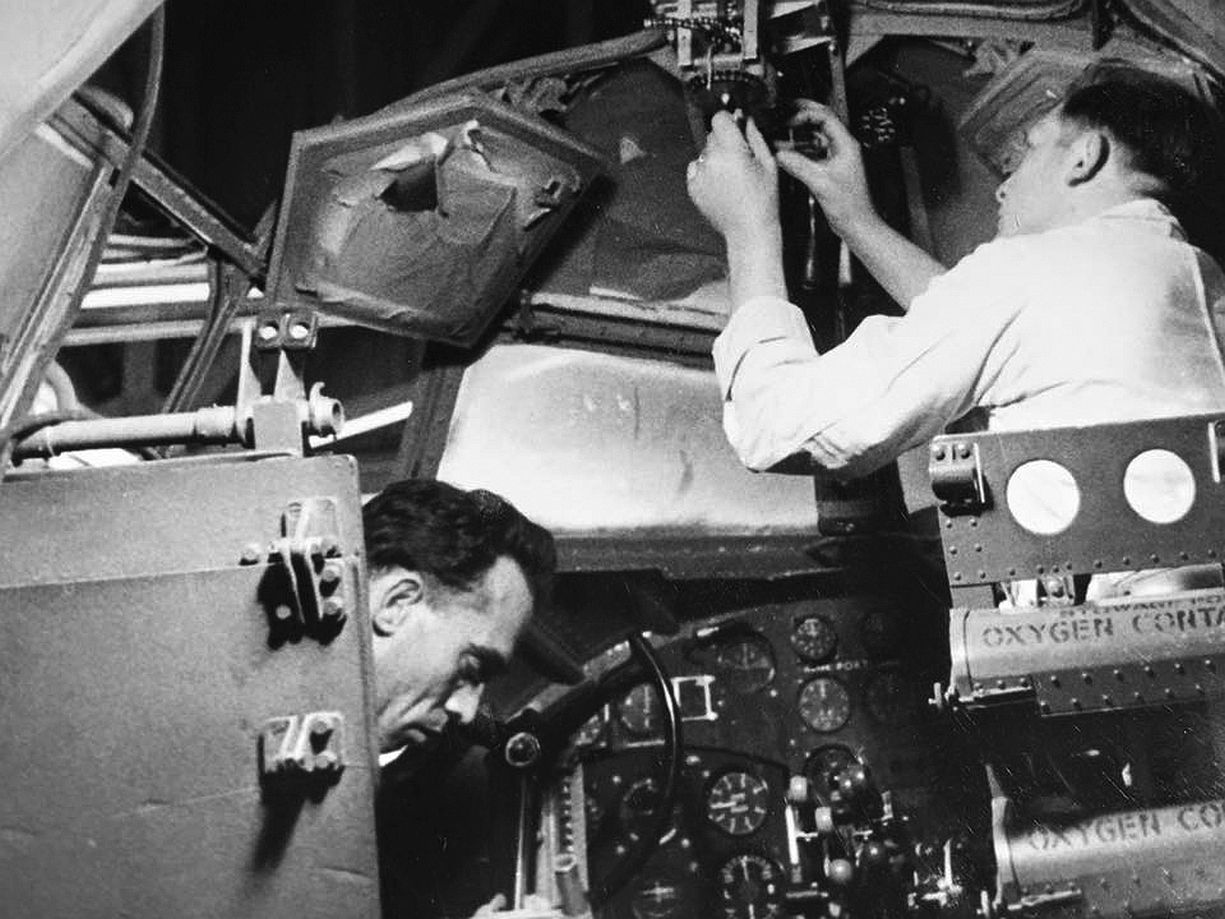

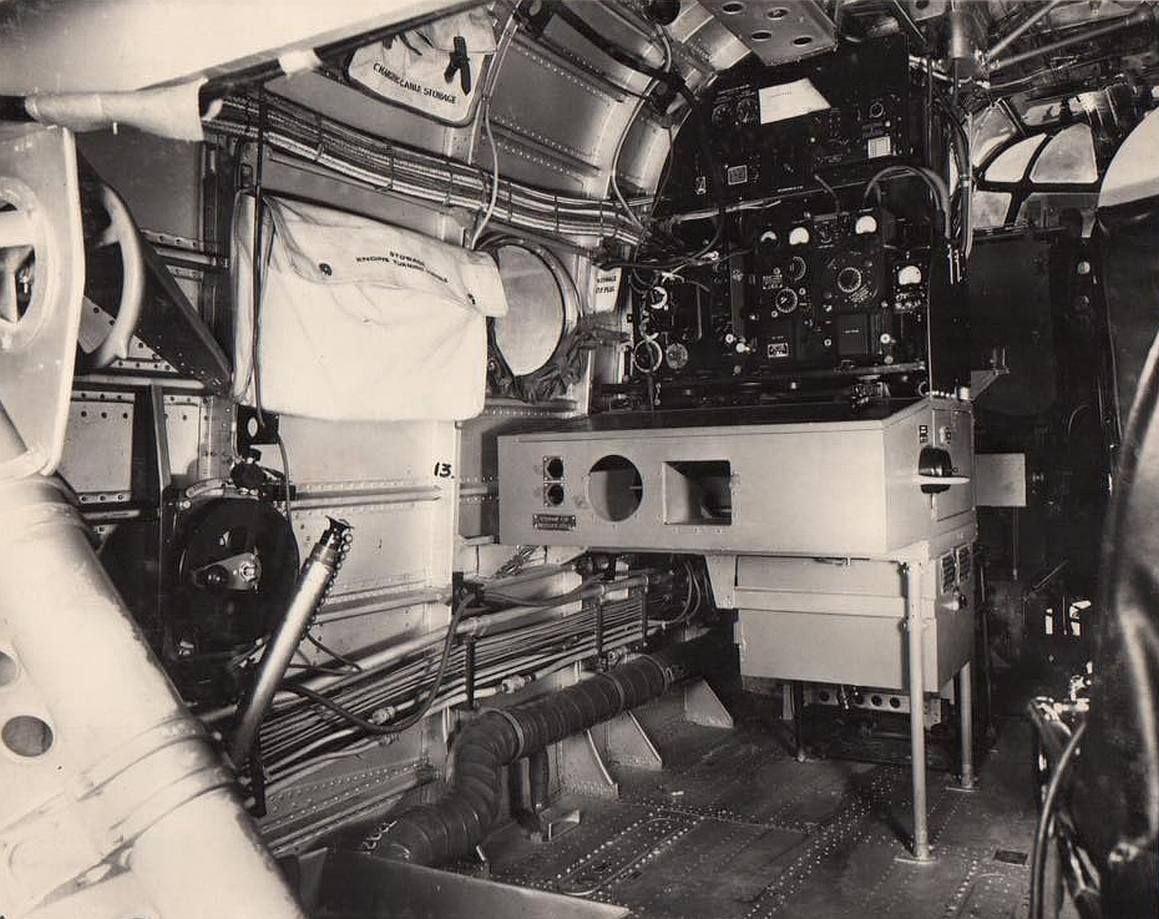

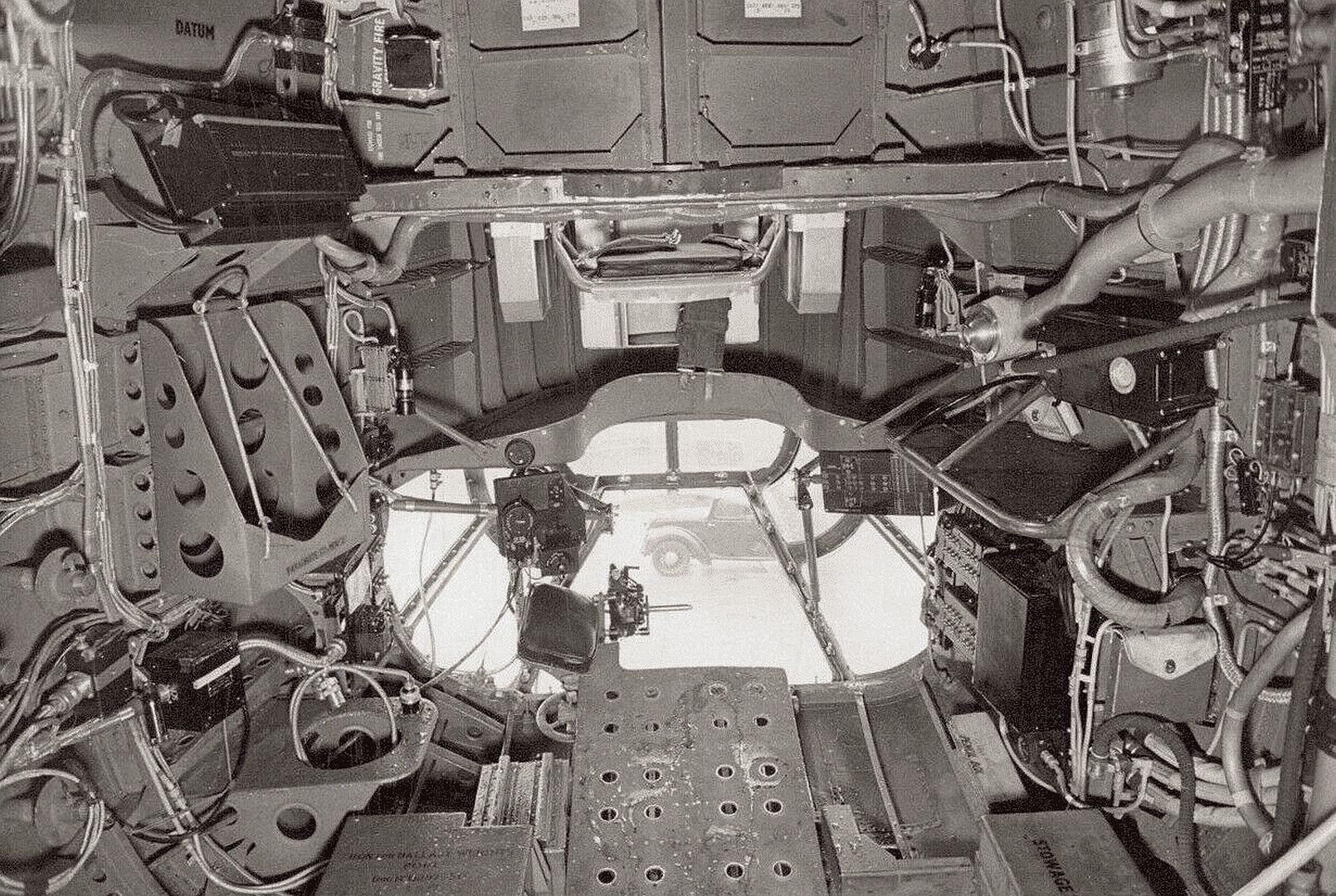

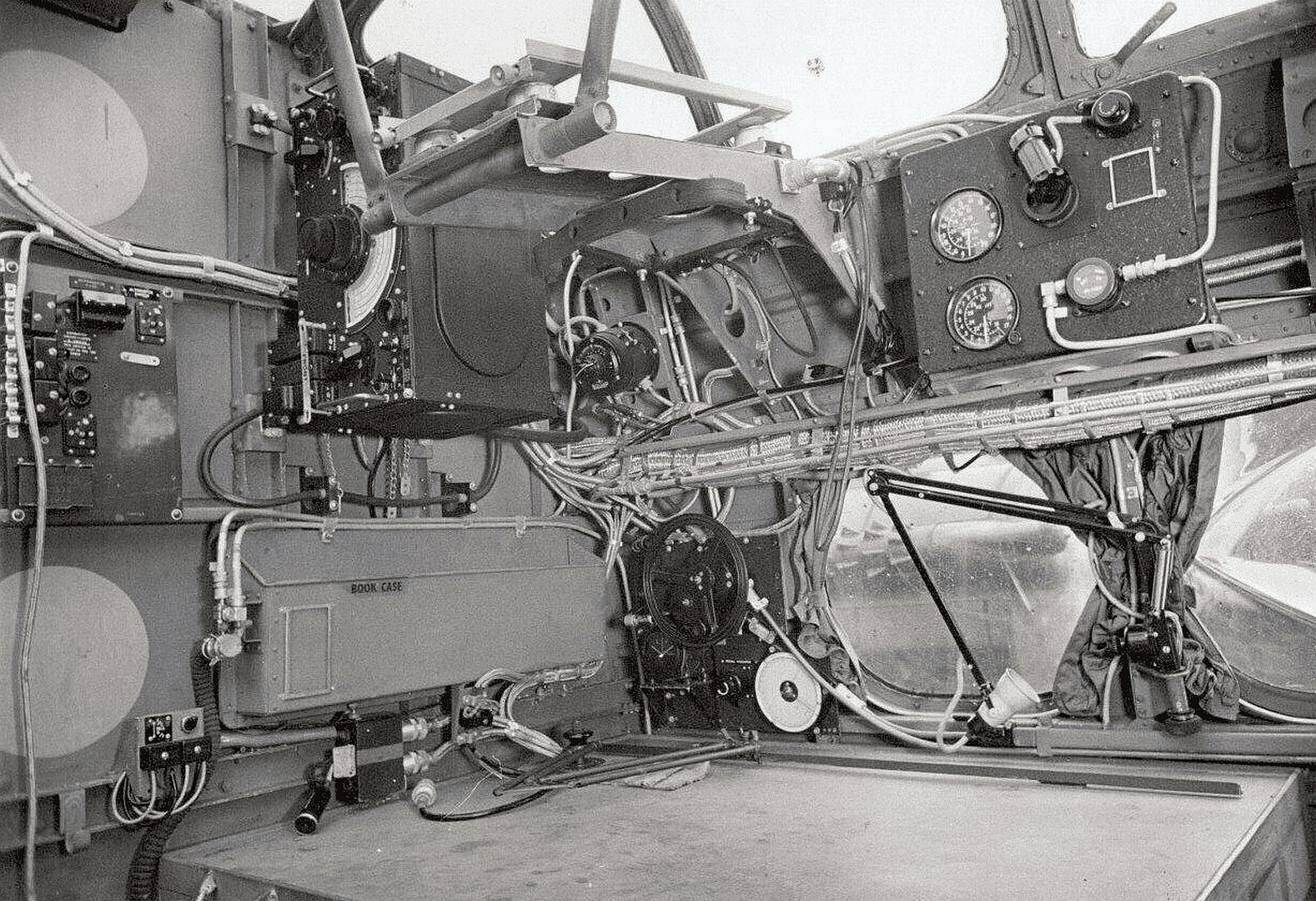

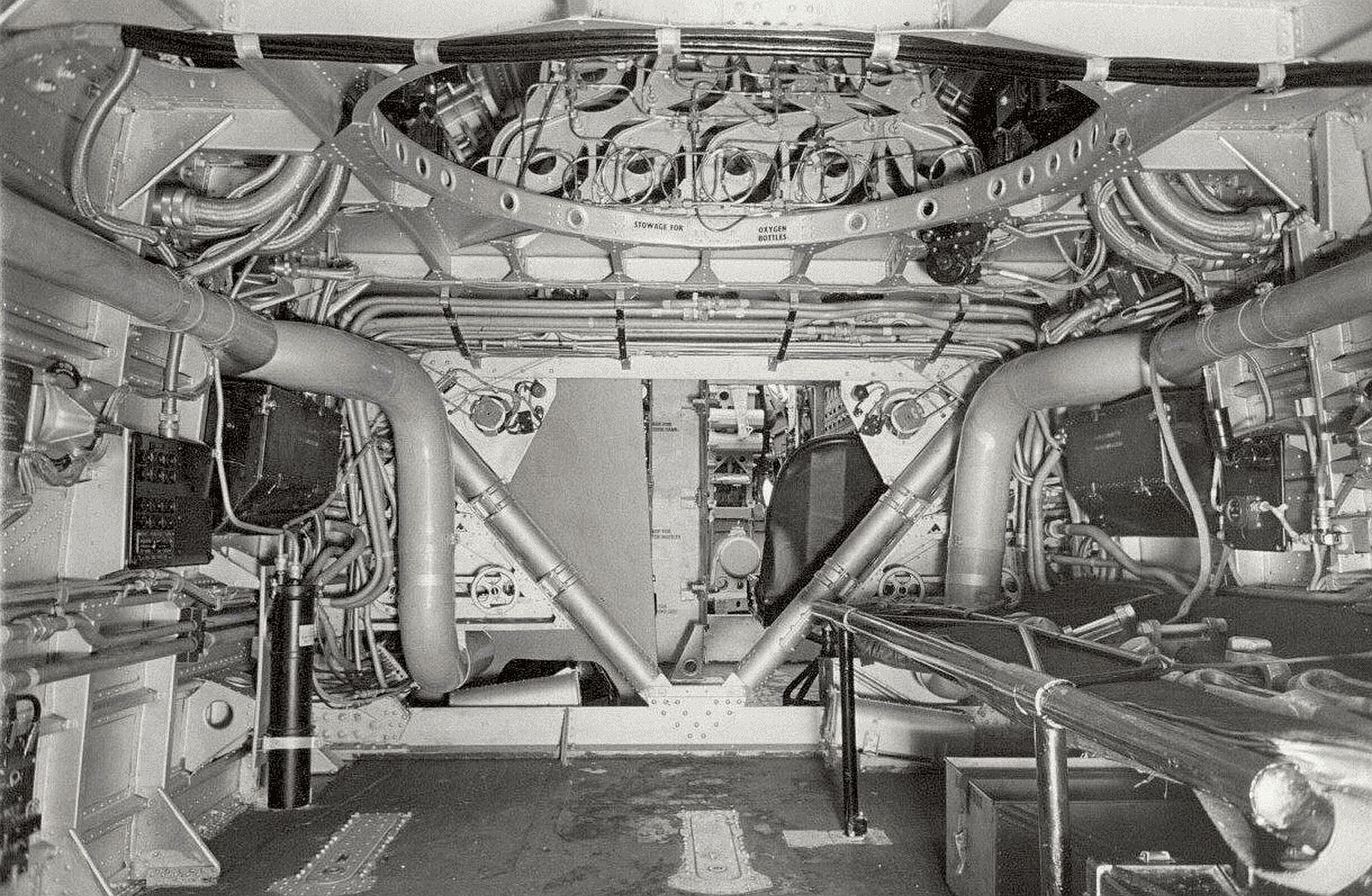

Below enjoy right click ad save as for details

Regards Duggy -

Main AdminUpdated.

Main AdminUpdated.

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources